The Reds are coming – the Mandarin Reds, that is and their work is showing up on gallery walls around town. Since 1980, artists from Beijing and Shanghai have been straggling into New York and Boston, loaded down with questions about freedom and modern art. They have been invited by universities or government programs or come on their own steam. Ranging from their twenties to almost 50, with hair long, short or punky, they are laboring with acrylics, oils, and Chinese ink in upstairs flats in the farthest reaches of Queens and heatless studios in the East Village. They have weeded gardens, renovated kitchens and taught drawing classes at Harvard to pay the bills. For better or worse they are here to figure out what it means to make art in the West.

The Reds are coming – the Mandarin Reds, that is and their work is showing up on gallery walls around town. Since 1980, artists from Beijing and Shanghai have been straggling into New York and Boston, loaded down with questions about freedom and modern art. They have been invited by universities or government programs or come on their own steam. Ranging from their twenties to almost 50, with hair long, short or punky, they are laboring with acrylics, oils, and Chinese ink in upstairs flats in the farthest reaches of Queens and heatless studios in the East Village. They have weeded gardens, renovated kitchens and taught drawing classes at Harvard to pay the bills. For better or worse they are here to figure out what it means to make art in the West.

With the Cultural Revolution as their reference point, these artists straddle three generations. Several came of age during the CR: Wang Keping and Qui Deshu, now in their late thirties were Red Guards in the late 1960s; Zhang Hongtu, a few years older, could not be a Red Guard because his father was labeled a rightist. Twenty seven-year-old Ai Wei-wei and Yan Li, 31, were too young to participate, but both lived with parents who were severely persecuted. Yan Li and Chen Yifei, 39, lost parents to that revolutionary movement. Yuan Yunsheng, approaching 50, was attacked as a rightist during the late 1950s, exiled in Northern China, then rehabilitated to Beijing’s leading art academy after the Cultural Revolution.

Some of these artists were trained in China’s most prestigious art schools; others had no formal training. The younger artists seem weightless in the West as they orbit around art-making in a nuclear age. They are wide open therefore most vulnerable to the onslaught of western culture. The mature artists appear confident in their search for the “middle passage” between East and West, more consumed with what it means to be modern and Chinese than postmodern in New York City.

Last December, 17 of these artists (two are in Japan, two in Paris, the rest in the U.S.) wrote a manifesto stating their concern for the “current state and future of Chinese art” and affirming the connection between freedom and creativity. In a sense, this declaration has been ten years in the making.

When I arrived in China in the fall of 1980, plays, short stories, paintings, and films were beginning to expose the wounds of the Cultural Revolution. One film, particularly popular among the over 40 set, dared to look further back and show the persecution of intellectuals that began with the anti-rightist campaign of 1957. Party bosses were licking their wounds, rehabilitating famous intellectuals and artists—at least those who survived the beatings, labor camps, torture and denials of medical care.

But another more recent movement had just been silenced – the New Democracy movement of intellectuals who wrote big character posters and published journals promoting democratic ideas. This movement began around 1976 and ended in 1979 when the government sentenced its most eloquent spokesman, Wei Jingsheng, to 15 years in prison and banned his journal, Exploration. Wei Jingsheng had argued against gods, emperors, and saviors. His manifesto called for a true workers revolution, which would guarantee justice and rights to working people, to the individual. “Without this fifth modernization,” he reasoned “all other modernizations are lies.” This was, of course, a direct attack on Deng Xiao-pings’s authoritarian “four modernizations” scheme.

My arrival in Beijing coincided with a mini-historical event. A group of dissident artists called Xing Xing (Star Star), that had emerged in the late ‘70s and received much attention for two previous “unofficial” outdoor art exhibits, were having their first—it would also be their last—official exhibit in the country’s most prestigious museum, the National Gallery. Most of the 26 artists in the Star show were of the Cultural Revolution generation, which means they had received little formal education and no art training. They worked at other jobs and had all been active participants in the New Democracy movement, or what they now refer to as Peking Spring. A sign at the gallery entrance stated. “Art must combine our free liberated spirit with the inspiration of creation.” It also explained that the artists “have the courage to explore” – a reference to Wei Jingsheng’s banned journal.

To the Western eye, this exhibition looked like a highly competent student effort at emulating early 20th century European paintings. Most of the work was impressionist, some was abstract; there was a sprinkling of nudes. The subject matter was mostly personal, the mood sad, and on the surface the tone was nonpolitical. In Chinese terms, the show was a break with orthodoxy. Since the end of the Cultural Revolution, art schools and academies had reopened and once again offered courses in Chinese traditional ink painting of birds, fish, flowers and horses or academic oil painting in the proto-socialist realist style of mid- 19th century Russia. Modern Western styles remained taboo.

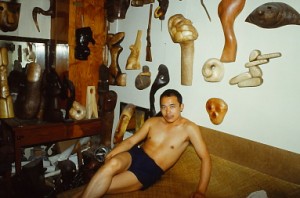

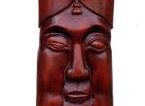

The one exception to the show’s personal emphasis was the sculpture of a Star Star leader, Wang Keping. Working in a traditional Chinese medium that had been lost for centuries, using the natural knots and gnarls of wood, he fashioned simple pieces critical of Party bureaucrats and the Great Helmsman himself. The largest piece, called Idol, was an over-sized face, recognizable as Mao—and Buddha. One eye was shut the other open. Keping explained to visitors “He wants to see who’s praying to him.” Along with several erotic sculptures, an art form prohibited in China, the work on display included totem-like heads with corked mouths and blackened eyes. About one called “Silence” Keping told a reporter, “It is about people who can see but are forbidden to look. They have mouths but are forbidden to speak. This is what happened to the grassroots movement in China.”

Since the previous year’s show, foreign journalists had been reporting their visits to Keping’s tiny apartment, where they saw a piece called “Backbone of Society,” a head with eyes closed, nostrils jammed, mouth tightly shut, a bump on the cheek. “That’s a cancer,” Keping would explain. “The indifference of these officials is the cancer of our society. They are bad cadres.” Another piece, a self-portrait fashioned from bamboo, depicts a creature with the body of a man and the head and tail of an ape. Above him is the spine of a book understood to be Mao’s Little Red Book. “It was such a weight on us we regressed into apes.”

These political statements were not totally out of sync with the times. That year Mao’s image was removed from most public places. Public criticism was leveled at corrupt cadres. And my office comrades at Radio Beijing, where I was an editor, showed their resentment of and frustration with the privileged, do-nothing Party hacks.

But Wang Keping’s pieces were curious in a country that for 30 years had promoted socially uplifting art—even more curious coming from someone who was the son of a Communist Party writer and a Red Guard in 1966. In the spirit of that time, Keping, at 17, had burned foreign magazines and books, helped to destroy a church and its artifacts, criticized teachers who spoke foreign languages, and denounced Western art as decadent.

When I met Keping, he was a script-writer for the Central Television station. It was because his scripts were never produced that in 1979 he turned to sculpting whatever chunks of wood he could find as a way to concretize his ideas and feelings His openness to foreigners, welcoming then to his studio, caused some of us concern, since other Chinese were in jail for such open communication—especially with reporters. The reticent and soft-spoken Keping would insist he was unafraid: “The Chinese people have been afraid for too long.” Repeatedly he would tell friends and reporters. “Art should not be made to serve politics, and politics should ensure full artistic development.”

Today, Keping looks back on 1980 as an open year for artists. Deng Xiaoping was still struggling for control; the top leaders weren’t paying too much attention to artists. That year Zhao Dan, the famous film actor, made a powerful statement from his deathbed that stunned everyone with a 30 year memory: the Party should not control artists and writers. “Who ordered Marx to write?” Zhao asked, “or Lu Xun, (China’s most celebrated 20th century writer)?” But this period of questioning was brief—as fleeting as the Hundred Flowers movement in 1957.

Keping had been dodging plainclothes police for several years, but when a short chapter about him appeared in Fox Butterfields’s 1981 book, China: Alive in the Bitter Sea, he began getting visits from the Security Bureau. He always maintained he had nothing to hide. Although he applied for a passport when he got married in late 1981, it was three years before he got permission to leave.

In the meantime, another Star Star member was jailed for her desire to marry a French diplomat. Other members were denied permission to change from factory to art-related jobs. The talented Star painter, Huang Rui, now living in Tokyo, was assigned to the boiler room in his factory after asking to leave for an art job. The police closed another Star exhibit that Keping attempted in 1983. Now seven Star members are living in the West.

Keping lives in Paris with his wife and new baby; this winter he has been in New York to arrange shows and to visit the scattered Stars, organizing them to write the manifesto. In Paris, Keping has pursued the track he began in Beijing, an erotic and humorous approach to the natural contours and idiosyncrasies of wood. But he no longer makes overtly political pieces. His work reminds foreigners of Moore and Brancusi, but he makes it clear that he’s more drawn to Han Dynasty carvings, simple, abstract, and powerful, like African primitive sculpture. Because ancient Chinese art was destroyed or hidden during the Cultural Revolution, Keping did not see Han Dynasty work until 1980, when a foreigner showed him illustrations of it in a book. He also saw Moore and the African primitives for the first time, and recognized his own spirit in all three genres.

Living in the West Keping is more than ever convinced that artists need to be free of official control. But there is the sticky problem of the market place. At the Brooklyn Museum they tell him his pieces aren’t big enough. At O.K. Harris they tell him that although they show sculpture, few people buy it, and that Americans would find his figurative work uninteresting. Keping smiles softly and reiterates a common Chinese maxim: “I must walk on two legs.” Elaborating, “I must make one art for the bourgeoisie and another for myself.”

BUT isn’t that like China? I ask. “There you have government control over who gets supported as an artist, who gets shown and published. Here you have the market.” Keping’s sensual face with the wispy goatee first smiles, then turns serious: “But nothing in that system fosters creativity.” Almost whispering, he repeats. “Art cannot be dictated by politics.”

We are sitting in the Queens living room of one of Keping’s close friends, Bai Jingzhou. Bai’s wife of thirteen years, Pan Ze, is bringing plates of fried dumplings and bowls of soy mix with vinegar for dipping. Frail and attractive, Pan Ze has been working as a free-lance fabric designer since she arrived from Beijing last year. A table in the kitchen, covered with gouache paints and felt markers, is her work space. Pan Ze’s depression at leaving family behind in China is straining her relationship with Bai. Today she hardly talks.

Bai Jingzhou left Beijing in 1981 and studied painting at the University at Carbondale before coming to New York last year. In Beijing he was a stage designer for television, which is how he met Keping. A series of his etchings, scenes of the Illinois countryside, line one wall. A large romantic landscape in gouache, all blues and greens, hangs opposite. Their technical proficiency is echoed by Dan their 12-year-old daughter, who is tackling Mozart on a piano in the other room.

Jingzhou is more high-strung than Keping, more talkative, more agitated by my questions. His energy seems wired to his small frame. In Beijing he painted in the realistic style. Despite that orthodoxy, in the early ‘70s he was criticized for painting a portrait of a young girl with bare arms. I ask about Mao’s famous talk at Yenan on Literature and Art which laid out principles for socialist art in China: art must communicate and please the masses; artists and intellectuals must change their consciousness, art must be positive rather than critical. Bai speaks bitterly: “Mao’s Yenan talk has been a yoke on artists. Each artist must work out what he feels is right.”

As if to prove that he is not a slave of Western art, Bai emphasizes that his work has not changed much here. He has just exhibited a group of his recent paintings with Keping’s work in a Chicago gallery. They are all landscapes of Beijing which, he says, reveal his thoughts about Chinese history. Power is a persistent theme. One painting, an image of the massive red brick wall around the Forbidden City dwarfing two men playing chess in front, symbolizes the continuation of a self-protective ruling class. Its power and privileges, he believes, have not changed with liberation. Mastering the official aesthetic, he has turned it on the system.

Jingzhou is not much interested in abstract art, but he gets animated when I suggest that for American artists, abstract expressionism represented a move away from social and political concerns; not coincidentally it emerged in a conservative era and the American government exploited it as a symbol of Western freedom. He quickly translates what I’ve said for Keping, who, in his usual manner, smiles softy and whispers, “Maybe that’s why China is finally beginning to tolerate abstract art.”

But what about the social responsibility of the artist? “Social responsibility can be expressed in different ways” Keping responds. “Not just be criticizing bad things, but by stimulating the imagination of the people. Artists can be critics and visionaries. It’s the moral condemnation of artists which is destructive.”

Mao made a success of promoting theory,” Jingzhou adds, “but he failed society.” He tells the story of Mao moving into government headquarters near a park in Beijing: he had all the flowers torn up and planted vegetables. Jingzhou shakes his head in disgust.

“Some flowers are beautiful,” Keping reflects, “and some smell sweet. Mao would scorch all the flowers, turning them into bitter incense.”

“We are the torched flowers of China” whispers 27 year-old Ai Wei-wei, another Star Star member now living in the East Village. As with his close friend Yan Li, the silencing of the New Democracy movement was his final disappointment in China. Weiwei left in 1981 with the help of his girlfriend’s relatives in the U.S.; Yan Li arrived in New York last fall. Both had been labeled and criticized as sons of rightists.

Weiwei’s father, Ai Qing was one of China’s popular poets during the revolutionary movement of the ‘40s. Like many other patriots, he spent several years in jail for his efforts in the Anti-Japanese War then went to the liberated zone of Yenan to join the Communist Party and write political poetry. But even in those years, this independent and outspoken poet was at odds with the Party. Like many other intellectuals, he produced less and less after Liberation. His criticisms grew, and by 1957, during the first anti-rightist campaign, he was purged. “He was charged with not writing what the Party wanted him to write,” Weiwei explains. First, Ai Qing and his wife were sentenced to two years of hard labor; then the family was banished to the Western edge of the Gobi Desert. During the Cultural Revolution Ai Qing was again severely criticized (because he had been branded a rightist in the past) and sent to an even more remote village to clean out latrines for seven years.

YAN Li was 12 when the Cultural Revolution broke out. Students ransacked his grandfather’s house, and three years later his grandfather committed suicide. Yan Li’s parents, both scientists, were sent to the countryside for nine years. Despite his history in the highly dangerous Communist Party underground in Shanghai during the ‘40s, Li’s father was now accused of being a spy because of criticisms against the grandfather. While in the countryside, Li’s father became ill and was denied medical care. When he returned to Beijing there was no job for him. He died at 54.

Both Wei-wei and Li were marked by who their parents or grandparents were. Yan Li felt hopeless: “I cannot change who my grandfather was.” Wei-wei seems to have absorbed the rebellious nature of his father. “I have always been a rebel,” he says with a guilty smile.

When Wei-wei’s family returned to Beijing after the Cultural Revolution he began studying painting with a friend, joined the Star Star group and was swept up into the New Democracy movement. “It was a movement from the heart” he says in a faraway voice. “People expressed themselves freely. Even though the country had been through a terrible experience, they felt there was the possibility to make a new start.” His face becomes strained as he continues. “With the jailing of Wei Jingsheng, those hopes were smashed. It was the biggest disappointment for young people in China. Our spirits collapsed.”

Yan Li was also involved in the New Democracy movement. Missing out on schooling during the Cultural Revolution, he educated himself while working in a factory, began painting and writing poetry, then joined Star Star. “It was a period when the strongest need was for free expression,” the youthful Yan Li tells me. “Not intellectual analysis so much as expression.”

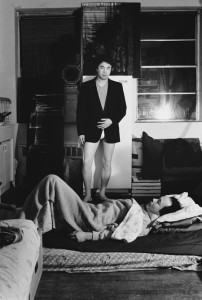

After he arrived in the US, Wei-wei studied English at Berkeley while working as a gardener. Then he came to New York to study art, first at Parsons, then on his own. “I don’t like to be told what assignments I have to do. I am not looking for that.”

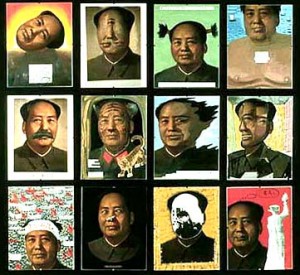

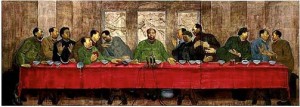

At his work space near Second Avenue we look through stacks of paintings. There’s a messy impressionist landscape reflective of his China period. On the wall is an Andy Warhol-inspired triptych of Mao’s image floating on a black background. In another series of paintings the artist is wrestling with silhouettes of the Mona Lisa. Our conversation keeps drifting to the problems of discipline versus freedom, tradition versus avant-garde. Wei-wei, more than any of the other artists, seems mired in this problematic. “Artistic freedom is so important, but then what?” he asks. He glances at the book by Duchamps he’s been carrying around “How does one artist get noticed? How do you survive? What is significant?”

The tall, handsome Yan Li looks like a suburban punk with his hair clipped short at the sides and long in the back. He rents a room in Queens, studies English in Manhattan and follows the East Village art scene. In February he had a private loft exhibit that included several paintings he did in Beijing.

The China work is surreal, emotional, and playful, using brilliant colors and clean lines, depicting half-animal, half human creatures. But in New York he seems to be going through the youthful regression that an outsider’s cursory glimpse of East Village art might lead to. He plays sarcastically with the canvas as an object, cutting it up, making constructions from it and drawing on it. He may be having fun, but the work, like Wei-wei’s, feels cut off from his experience.

If Wei-wei and Yan Li failed to receive Mao’s good news, if they seem more disturbed than the older artists by the collapse of the New Democracy movement, they are also more adrift in the West. Perhaps that’s because they are both more raw, more open to its stimulants. Although they are intrigued by the satirical potential in art, they seem more easily confused by Western cliché’s. Newcomers in Western popular culture, they don’t realize that commercialization has made certain images powerless.

Zhang Hongtu’s father was also attacked as a rightist because he had agreed with those calling for a multiparty system in 1957. But since he was a Muslim and Arabic scholar and his translating skills were needed, he was not sent to the countryside. “Mao believed intellectuals were simply tools.” Hongtu laughs sarcastically.

In the late ‘50s, Hongtu passed the rigorous competition to attend the coveted middle school connected with Beijing’s Fine Art Academy. This competition, a legacy of the old system, ensures the perpetuation of the intellectual class. It ended with the Cultural Revolution, then was re-established in 1976. In a land of a billion people, restricting advanced training to a handful of prestigious academies in Beijing and Shanghai gives China the most elitist educational system in the world.

The academy’s approach to Chinese brush and ink painting, as well as to Russian academic drawing, was “Copy, copy, copy, so that every student’s work looks the same,” says Hongtu. “We had to copy without understanding the meaning of what we are doing. There are no whys, no understanding about what is art or spirit.” This did not change during the Cultural Revolution, only the models. According to Hongtu, during that period some artists painted so may posters in one style, and so many images of Mao, that afterwards they were unable to paint. “It was both an artistic and a psychological problem” he adds. Whatever Western art was available through books was labeled bourgeois, decadent, and bad. “Even the East German school of socialist realism, which I found more exciting than the Russian, was taboo.”

DURING the Cultural Revolution, Hongtu spent three years working on an army farm: “I had the opportunity to live with peasants and enjoyed their rural life.” Unlike Wei-wei and Yan Li he did not see rural work and manual labor as punishment. His complaint, so common among “sent down youth,” was that there were no books. Nor were they allowed to paint or draw. It was during those years, he says, that he realized the Cultural Revolution was really about the destruction of culture.

Hongtu used to agree with Mao’s Yenan Talk. “Art should serve the people,” he insists. “It should communicate. But is socialist realism the only style that people can understand?” Abstract art worries Hongtu less than Mao’s abstract concept of “the masses” and “serving the Communist Party.”

After returning to Beijing from the countryside, he graduated from art school and went to work in a jewelry factory as a designer – an assignment in which he had no say. He continued to paint prolifically at home on his own and exhibited with other artists in a similar situation. In 1981, when one of his paintings received a lot of attention and the National Gallery bought it, he was offered teaching positions at several prestigious academies. His work unit, the jewelry factory, refused to let him go. Since the work unit controls housing, food and clothing rations, and other basic commodities, there’s no such thing as simply quitting. So Hongtu applied for a passport to leave.

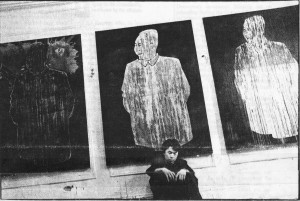

Now the 42 year-old painter lives with his wife and nine year-old boy in a two room apartment in Murray Hill and attends classes at the Art Students League. On a cold Saturday morning he takes me to his studio in the East Village. “In China I never thought about the psychological part of painting.” He says while moving giant canvases that dwarf his petite frame. “Here I am trying to move from my heart to an idea.” He shows me his recent work, a series of large expressionist canvases with thick black backgrounds and brilliant red figures of men, ghosts, or oxen in the foreground. In some he scatters huge boulder shapes across a black landscape. Often the paintings convey a feeling of stress, of alienation between people and nature. “They represent my feelings in New York,” Hongtu explains, adding that he is also struggling for harmony, a motivation deeply rooted in Chinese art. But despite his self-assured handling of the paint, the imagery doesn’t convince me. It feels too influenced by current neo-expressionist work.

Despite Western freedoms, Hongtu sees that China-trained artists face problems with creativity here. In China, he was always in the vanguard, always experimenting with modern styles. “But here in New York,” he shakes his salt and pepper head, “I’ve had to start form zero.” His palette has changed from subtle, soft earth tones to thick black and brilliant red acrylics. “Western culture is always boiling” he laughs. “In China it’s always temperate.” Reacting to the recent exhibit of art from Shanghai University (at Hunter, Baruch and Lehman colleges), Hongtu says, “They’re still doing the same thing they were before I left China. It’s boring and not very good.”

Hongtu has the energy, curiosity and drive of a 20 year-old. But he is a mature artist, uprooted and groping. When I question whether he is satisfied with his current work, he emphasizes that it is experimental. Then, laughing, he says, “Recently I saw a headline in the Daily News. It said “I want to have one more night before reality sets in.”

The oldest of the group, Yuan Yunsheng, was embroiled in controversy before leaving Beijing several years ago. The cultural bosses were outraged by two highly stylized nudes in his 1979 mural for the Beijing Airport, a figurative work depicting the Water Festival in Yunnan, an annual celebration of one of China’s minority groups. At first, the nudes were covered by a curtain that people could peek behind. Then they were boarded over.

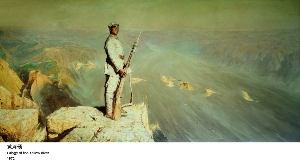

In the ‘50s Yunsheng studied at the central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, until the anti-rightist campaign, when he was criticized for being anti-Russian and having Western attitudes about art. He was first sent to a suburban labor farm and then to northern China (like the Gobi Desert, this location is the equivalent of Siberia) to be a teacher at a Workers Cultural Club (akin to the YMCA). After 16 years there he traveled to the far south of China to sketch in the jungles of Yunnan. A book of his bold expressionist drawings from that trip re-established his reputation as one of China’s most talented artists. He was rewarded with a teaching post at the top art academy in Beijing – and the airport mural assignment.

Three years ago Yunsheng came to the U.S. on a visiting artists program, and now he and his girlfriend live in a modest upstairs flat in Queens. Once a week he commutes to Boston to teach drawing at Harvard. In 1983 he painted a giant mural at Tufts University, a partly figurative and partly abstract rendering of legends about liberation from Yunnan’s Dai people. Some sections of the mural are reminiscent of early German expressionism, others of Picasso. Yunsheng says he drew inspiration for this project from the Mexican muralists who “fuse traditional and modern expression” and from the Dunhuang cave paintings in China. (The walls of the Dunhuang Caves were painted over a thousand year period combining different eras of Chinese art and history as well as Buddhist and Indian influences).

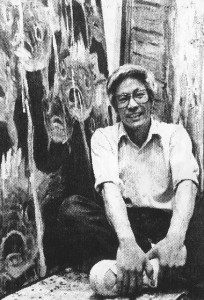

For Yunsheng, the importance of going to Dunhuang was to study the simplified line styles. Line has always been of primary importance to Yunsheng; that’s evident in the work he has been producing here—large-scale ink-on-paper paintings of abstract, elongated figures. By exploiting the abstract qualities of his materials and Chinese brush techniques, he creates bold and sensual images.

“For a hundred years in China every political movement has posed the question of heritage versus Western values and models” he says “For example, can we use the Chinese as a basic idea and borrow from western ideas?” For him any dictate on this is absurd. Individual artists must work it out for themselves.

Yunsheng, with jaw-length straggly hair and a wispy short beard, leans back in the chair behind his huge work table. What would otherwise be the living room is his studio, dominated by the over-sized felt-lined table, the typical working surface for ink painting. Jars filled with Chinese brushes stand around the edge. Chinese and Western art books line the walls of the room.

“It is useless to keep looking back at the ancient culture as great. More important, we need to develop fresh perspectives on that culture, appropriate to our situation today. Chinese artists need to find themselves, their true selves first.”

All the artists living in the West echo this emphasis on self-knowledge. Although it may sound hackneyed to Americans jaded by pop psychology and a whole cultural era of self-absorption, for Chinese intellectuals and artists self-exploration and individual expression come out of a different political history and have their roots in the early 20th century intellectual movement that launched their revolution.

For 37-year-old Qiu Deshu, who arrived from Shanghai last fall to be a visiting artist at Tufts, the hard experiences of “class struggle” left him seeking spiritual strength through his art. As a Red Guard, Qui Deshu made posters promoting revolutionary slogans; later assigned to a workers cultural club in Shanghai, he painted posters illustrating government policy or advertising movies. Disillusioned with the Cultural Revolution and state-sanctioned art he turned to painting on his own as a “way to elevate my life values.”

At first, Qiu Deshu returned to traditional painting, but quickly tired of copying old masters. It was a time when others were beginning to experiment with doing modern things with calligraphy and traditional techniques. Qiu took this a step further by recombining calligraphy and painting, which had diverged 2000 years ago. He kept manipulating them in increasingly abstract directions. With other like-minded artists he formed the Grass Grass group in Shanghai in 1979.

Along with Yuan Yunsheng’s, Qiu Deshu’s work represents the cutting edge of modern Chinese art. Combining brush and ink, brilliant color, a complex paper tearing technique and carved seal stamps, his work is entirely abstract. Looking at a huge triptych of paintings on paper which he exhibited at Tufts Gallery in February, listening to him talk about the search for harmony and truth reminds me of the essential differences between Western and classical Chinese art. For a Western painter the task is creating illusions, for the Chinese it was to summon up reality – not to describe its appearances, but to manifest its truth. Picasso was the first Western artist to express something similar: “The question is not to imitate nature, but to work like it.” This is why many Chinese artists who are mining their own classical tradition are also drawn to certain modern Western artists.

Qui Deshu’s complicated technique for creating a network of vein-like lines through his paintings also emphasizes the importance of negative spaces, a central concern of Chinese aesthetics. The effect of those lines (like living tissue of the universe under a microscope) evokes the crucial concept of qi, the eclectic, spiritual energy of a painting, which connects everything.

Qiu Deshu seldom showed this work in China because cultural officials thought it was evil and that he was crazy. “They don’t understand abstract work even though Chinese painting and calligraphy are abstract,” he says. “For me, Western abstraction is like turning a corner. And the cultural bosses can’t do that.”

In his barren Somerville flat, Qiu’s large six foot frame is perched on a kitchen chair. With animation he draws a diagram to explain the dilemma for modern Chinese artists. The route forward is through difficult mountain ranges. On one side is traditional art; on the other Western art. (Klee and Miro, he says are in the middle of both traditions). He describes the journey as hazardous: If you’re unable to go through those mountains, you fall into Chinese or Western clichés.

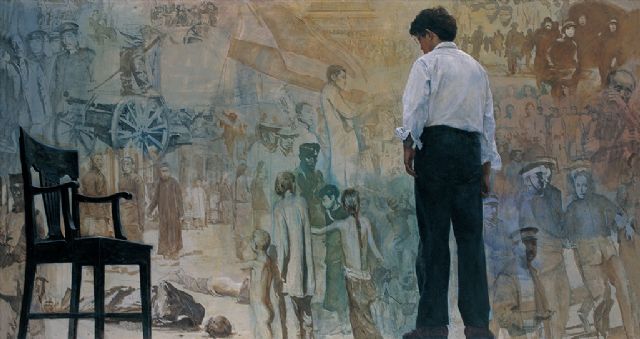

Of all the Chinese artists working in the U.S., the biggest curiosity is Chen Yifei, who was an official artist in Shanghai, one of China’s most talented and applauded. His gargantuan rendering of the army’s 1949 liberation of Beijing hangs in the Army Museum in the capital. In his stunning 1981 painting., Thinking About History, the artist appears in the foreground depicted with airbrush-like realism. He is looking at a sepia impressionist mural of the 20th century history of China’s intellectuals as they led the various movements to liberation.

Chen Yifei was the first of the post-liberation wave of Chinese artists to come to the U.S; he came in 1980 on a student visa to study at Hunter College. Now he is selling his paintings for anywhere from $15,000 to $30,000 a transition greased by Armand Hammer. And what does he paint? Nineteenth century style impressionist images of Suzhou and Hangzhou, two of China’s pretty and small garden cities, as well as startling, realistic portraits of upper-class Americans—especially classical musicians. In one a young woman plays the flute with an image of Beethoven on the wall behind her.

In China, Chen says, the Party criticized him for not being idealistic enough in his renderings of peasants and soldiers. Here, he has succeeded by idealizing the bourgeoisie. He may well be the foremost portrait painter in the world. He has perfected the academic style and absorbed the lessons of 18th and 19th century European painting techniques; his paintings are the work of a brilliant craftsman with an uncanny sense of the market. It’s no surprise that he says he doesn’t think of himself as a Chinese artist.

Although Chen Yifei repeats what I have heard from the other Chinese artists here – “It’s important to find yourself, your own individual style” – his name is not on the manifesto. The other artists have no contact with him and say they have no desire for any. When I ask them why, they say they think Chen is a Party member, which he denies.

Chen lives in a spiffy doorman building on the upper East Side. His bright and airy apartment is filled with elegant furniture and electronic equipment. He greets me graciously in gray wool pants, white shirt and a tweed sports jacket. I recall our meeting at a party for Wang Keping, a few weeks earlier. The other Chinese artists were dressed much like any working painter (Qiu Deshu had on an oversized ‘40s suit with sneakers). Chen Yifei was dressed like a banker and was handing out business cards.

After his apprentice makes me tea, we talk about his history. He is the son of an engineer and a school teacher. He carefully explains the significance of getting into the middle school of Shanghai Art College. Three thousand applied to take the exam. Half were chosen to take the exam for 100 positions in the high school. After completing this program, three were selected for the college oil painting program. He was one of the three.

During the Cultural Revolution, both his parents were persecuted and developed severe health problems. Chen nursed them at home until they died in the early ‘70s. While Chen himself was sent to the countryside briefly he was supported as a government artist and by the mid-‘70s he had gained a considerable reputation executing huge socialist-realist oils on revolutionary themes.

Now he says he realizes the importance of his technical academic training. After studying at Hunter College for two years, he went to Europe and absorbed the lessons of the museums. When he returned to New York he began producing his Sargent-style portraits and impressionist landscapes. Both his midtown gallery shows in 1983 and ’84 sold out immediately. Last year he had a show at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington. Proudly, he shows me a photograph of Armand Hammer presenting one of his paintings to Deng Xiaoping. But this success has its drawbacks. Chen has a waiting list for portraits and landscapes. “I would prefer to do paintings of ballet dancers” he sighs. Ah…the marketplace.

It would be easy to judge these artists as cultural defectors, opting for Western ideas and successes. Forgetting the trauma they have witnessed, we could say their commitment to individual expression is thoroughly Western and bourgeois. Yet if I try to get beyond my Western categories of thought, I can perceive their attitudes about art and artists as thoroughly Chinese – Confucian and socialist.

One of my biggest difficulties in China was sorting out attributes of New China from legacies of the Old. Most of these artists stand firmly in both those worlds more than they stand in the West. Some harbor Confucian notions of the artist as a true intellectual with cosmic and humanitarian concerns rather than material ones. Even the youngest, Wei-wei, tells me how uncomfortable he is with artists here. He wants to study in all disciplines, experience everything and travel as part of shaping himself as an artist. To a Westerner this might sound romantic or bohemian. It is also Confucian. Confucian too, is the fact that all these artists are men. Only now are women entering the fine art academies in significant numbers.

The artists’ distaste for the American art market is both Confucian and socialist. In China certain artists have always been supported by the government – the Communists didn’t invent this – and everyone is guaranteed work and housing (the Communists did invent this); here, sooner or later, every artist has to deal with a callous and fickle marketplace. I suspect that the mature artists coming from China will have less trouble with art-world hype, having endured the dogmas of revolutionary romanticism.

For all these artists, being in the West offers their first focal distance on their culture – so necessary for self-understanding. One Shanghai abstract painter whose work has become more “Chinese” since living in New York, said, “I never understood Chinese food until I tasted a hamburger.” Their dilemma is complex. Chinese classical art, with its concern for cosmic harmony and its strict, conventional forms, differs radically from western art. A Chinese character has rigid rules of stroke and order, but an artist’s nuances of expression reveal a world about his character (in both meanings of the word). Again and again, these artists tell me how meaningless freedom is without form, rules, discipline.

Wrapping up our interview, Zhang Hongtu said, “What China’s art world needs is some Beethovens, so that artists, like pianists, could interpret their masterpieces in a myriad of ways.” This is a thoroughly Chinese idea about art. In the West we look for shocking inventions, new forms, new ideas new media which quickly become objects of consumption and are just as quickly discarded. In China, interpreting the subtleties of an idea is more important than inventing it.

As these artists pursue self-expression in the West, they are beginning to absorb the painful lessons of the art market, to confront a mentality that marginalizes or romanticizes non-Western art and ignores actual non-Western artists who attempt a fusion with the modern spirit. Under the weight of these biases they may cave in to the demands that they become like Western artists. Or, with time and confidence, they may dare to play with the cultural mirror, reflecting back on the mysteries and pains of their experience while flashing new angles of light on the West. And if we can play with them we may get a glimpse of the other side of the moon in a language we all want to learn.

*Only the photographs of the artists by Darren E. Lew appeared with this article in the Village Voice. I welcome comments and corrections.

[…] feature in the Village Voice (“Is There Art After Liberation? Mao’s scorched Flowers Go West” http://gailpellettproductions.com/is-there-art-after-liberation-maos-scorched-flowers-go-west/ about the social, political and cultural upheavals their different generations witnessed and how […]