Our Lawns Are Killing Us

© 2022 by Gail Pellett

A version of this article was published on Medium in September, 2021

I live part of the year in a posh community on the Eastern end of Long Island. Many of the inhabitants —especially on the ultra-rich side of the tracks— probably think of themselves as environmentalists. Yet, they maintain enormous lawns. Acres of lawns. But even among our less affluent neighbors—middle and working class and tradespeople—lawns are ubiquitous. We are committing suicide by maintaining all those lawns.

Fertilizers and Herbicides and Extinction:

The millions of acres of lawns across North America—residential, golf, public and sports parks—constitute a massive deforestation project that has removed a healthy and complex ecosystem and replaced it with an artificial and poisoned landscape. The chemicals used to fertilize lawns and kill pests and weeds also kill vital insects, including pollinating bees and butterflies, while endangering birds and animals, fungi and soil microorganisms that we need for a functioning biodiverse ecosystem—an interdependent universe that we must start seeing ourselves as part of if we are to survive.

Scientists who study birds insist that pesticides and loss of habitat are leading to the collapse of species. Insects are facing a rate of extinction eight times faster than mammals and birds yet they are absolutely essential for our natural systems to function. Their loss could trigger a catastrophic collapse of our planet.

Meanwhile, Americans use ten times as much fertilizer on their lawns per acre than farmers use on food crops—more than 90 million pounds annually. They also use 80 million pounds of herbicides and produce another 26.7 million pounds of ground and air pollutants that spew out from lawn mowers and leaf blowers.

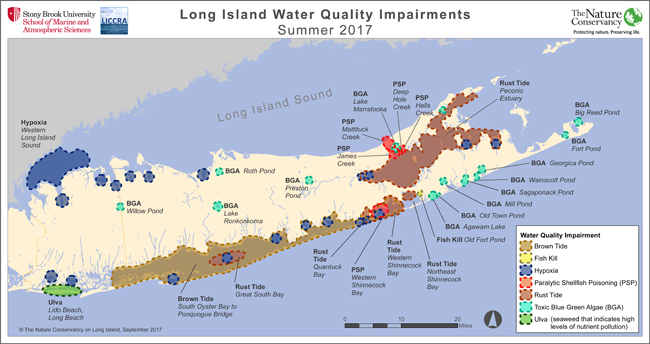

All those lawn chemicals leach into our ground waters and especially into the serpentine bays and inlets that define our community. Algae blooms are just one indication of the extent of this pollution in our interior bays and wetlands. Our house sits in the wetlands on an inner harbor near Gardiners Bay. We have watched the decline of shore bird and marine species over the past thirty-five years. And daily we are reminded that everything that you…we put into our yards and lawns we will eventually drink.

Fertilizers Loaded with Nitrogen:

Algae blooms, red tides, and dead zones in the waters surrounding Eastern Long Island have become an increasing problem. Fishing enthusiasts tell me those waters offshore are already dead. High nitrogen content in the water is the major culprit. It sucks out the oxygen that marine life depends upon. It also adds to the poisons in our drinking water.

Two decades ago, marine scientists studying the Peconic estuaries of Eastern Long Island discovered that more than l/4 of the nitrogen load in the groundwater came from fertilizers. That led Suffolk County (which covers the Eastern area of Long Island) to pass legislation in 2009 governing the use of fertilizers on lawns and farms. They stipulated that fertilizers could only be applied between April 1 and Nov. 1. That’s a seven-month period when you are allowed to use fertilizers. Hardly a restriction! And golf courses and athletic fields are excluded from this regulation. In Suffolk County that’s a huge exception.

The county legislation also stipulates that posters informing buyers about fertilizers and restrictions on application dates be posted in local stores. I have shopped for fertilizers in stores on Long Island’s East End and never seen such signs. That leads me to suspect there is little or no enforcement of these minimal regulations.

In 2012 New York State banned the inclusion of phosphorous in fertilizers which was starving fish of oxygen in local waters. While the most popular fertilizer brands—like Scott’s Green Fertilizer and Miracle Grow Lawn Food— now indicate the absence of phosphorous they are still nitrogen bombs. While one brand may indicate 27% nitrogen and 56% other ingredients, the secret is in those “other ingredients.” Like ammonium sulfate, and Urea, they are mostly nitrogen additives or boosters.

In addition to compromising our drinking water and threatening aquatic life, high nitrogen levels in fertilizers can cause the loss of certain plant species and depletion of soil nutrients. Nitrogen’s chemical interaction in soils also produces nitrous oxide or N2O, a greenhouse gas.

It is not only the use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers in our front yards that is dangerous to our environment and public health, but the very manufacturing process of fertilizers contributes to climate change through its significant carbon release.

“Carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide and methane are produced during the fabrication of fertilizers,” claims Lenore Hitchler in her 2018 article, Lawns Are an Ecological Catastrophe. “For every ton of fertilizers manufactured, two tons of carbon dioxide are produced. Most conventional fertilizers are produced using ammonia, which is extracted from natural gas, and two-thirds of natural gas is obtained by fracking.” It’s a highly destructive cycle.

A recent algae advisory on famous Georgica Pond surrounded by expensive homes on Eastern Long Island. Signs like this are common on Long Island, where blue-green algae blooms produce a powerful toxin, called microcystin, which can make people and wildlife sick. © Marian Lindberg

Creating a field of poison: Pesticides, herbicides, fungicides

There has been a long and sordid history behind the herbicides used on lawns. At first lead arsenate was applied, then came DDT and chlordane found to be toxic to birds and animals, then diazinon and chlorpyrifos—both hazardous. Elizabeth Kolbert in her article Turf War (The New Yorker, 2008), explains that “Diazinon came under scrutiny when birds started dropping dead around a recently sprayed golf course.”

In August of 2021 the EPA once again banned products with chlorpyrifos –used on all of our fruits and vegetables (and lawns) because it affects the nervous systems of young children. The Trump administration had eased regulations on this poisonous substance which has already permeated our food system.

Today the favorite brands of herbicides are Sevin and Round-Up.

When I Google the herbicide Sevin, I am warned: “Dust powder could be accidentally inhaled by people or pets. Exposure to carbaryl (the central ingredient) could cause dizziness, weakness, slurred speech, nausea and vomiting. Poisoning from this pesticide may cause seizures, fluid in the lungs or reduced heart and lung function.”

Carbaryl, claims Elizabeth Kolbert “is a likely human carcinogen, shown to cause developmental damage in lab animals, and is toxic to—among many other organisms—tadpoles, salamanders, and honeybees.”

Our other favorite herbicide, Round Up, doesn’t fare much better. Composed of 2,4-D or glyphosate, it is one of the two major ingredients in Agent Orange. Unfortunately, 2,4-D kills not only dandelions but also plants beneficial to lawns, like nitrogen-fixing clover.

Bayer AG who bought Monsanto, the original creator of Round Up, has been hit by more than 125,000 lawsuits claiming that glyphosate causes cancer. One federal jury payout for a California case came to $80 million. On May 26, 2021 the Wall Street Journal reported that Bayer, after losing three trials in 2018 and 2019, said it would pay up to $9.6 billion to settle existing Roundup cases that tie glyphosate to non-Hodgkin lymphoma and another $2 billion for future claims.

“Bayer AG said it will evaluate whether to continue using the active ingredient in its popular Roundup weedkiller in the residential U.S. market, in the wake of a court setback Wednesday in the company’s efforts to limit future liability over whether the product causes cancer.” Wall Street Journal, May 26, 2021

The patents have run out on glyphosate that Monsanto developed, so this ingredient for herbicides is produced widely around the world and many weed plants have become resistant.

Beyond Pesticides, an advocacy organization focused on the impact of chemicals on the environment, lists 30 of the most common pesticides: (herbicides, insecticides and fungicides) along with their health dangers and appropriate research sources. Sixteen are carcinogenic, 12 are linked to birth defects, 21 are linked to reproductive effects, 25 with liver or kidney damage, 14 with neurotoxicity and 17 with links to disruptions in the endocrine (hormonal) system.

A few years ago, Toronto banned the use of virtually all lawn pesticides and herbicides, including 2,4-D (glyphosate) and carbaryl, on the ground that they pose a health risk, especially to children.

Do the folks on the Eastern End of Long Island, or anywhere for that matter, really want their kids or grand-kids and pets playing on these lawns?

Water Use—Lawns are the single largest irrigated crop in America

The Western half of the United States, withering under long term drought, is facing a water shortage. A recent news item reported that some restaurants in Northern California send their guests to port-a-potties on the street. A hotel owner worries if showers will need to be replaced by hand wipes. The Colorado River that supplies water to millions in the West, is receding. Lakes are disappearing. Yet we are committed to lawns that require daily hydrating at rates larger than agricultural fields. A 2005 NASA study estimated that there are three times more acres of irrigated lawn in the US than irrigated corn.

The Natural Resources Defense Council determined in a 2021 study that three trillion gallons of water were used annually on lawns. The Environmental Protection Agency found that more than third of all residential water use in the United States currently goes toward landscaping.

Cacophony in the Neighborhood: The Invasion of the Mowers and Leaf Blowers

If you are still not alarmed by the chemicals we are spreading on our lawns and the volume of water it takes to keep those lawns green, take a hard look at the industrial equipment (mowers, blowers and weed whackers) with their antiquated engine types spewing gas residue all over our yards while emitting noxious fumes. It is estimated that lawn mowers and leaf blowers consume over 800 million gallons of gasoline annually in the U.S. The gas that leaks from those engines combines with the pesticides and nitrogen loaded fertilizers to create a lethal brew in our ground water and local bays. Again, remember you are drinking it.

GAS POWERED LAWN MOWERS AND LEAF BLOWERS ARE THE MOST POLLUTING ENGINES IN OUR LIVES. ACCORDING TO THE EPA, ONE GAS LAWN MOWER EMITS 89 POUNDS OF CO2 AND 34 POUNDS OF OTHER POLLUTANTS PER YEAR. A CANADIAN GOVERNMENT STUDY FOUND THAT ONE GAS POWERED LAWN MOWER EMITS ABOUT 48 KILOGRAMS OR 106 POUNDS OF GREENHOUSE GAS IN ONE SEASON.

The problem with the two-stroke engine:

Gas powered lawn mowers and leaf blowers are based on an antiquated technology – the two-step engine, that has been phased out for mopeds, moto-taxis and the like around the world. But they are still a ubiquitous feature of the landscaper’s arsenal when it comes to lawn culture including on the Eastern End of Long Island. Kolbert in Turf War reports that a Swedish study discovered that “using a mower for one hour has the same carbon footprint as a 100-mile car trip.”

The two-step engine is dirtier and less fuel-efficient than the four-step engine used in cars “because it sloshes together a mixture of gasoline and oil in the combustion chamber and then spews out as much as one-third of that fuel as an unburned aerosol,” writes James Fallows in his article, Get Off my Lawn, (Atlantic 2019).

What happens when leaf blower users don’t fill with correct gas or lubricants? Why is this worker not wearing mask or goggles against the pollutants the leaf blower distributes?

One study revealed that a two-stroke leaf blower emits almost 300 times the hydrocarbons and 23 times the carbon monoxide compared to a 2011 Ford F-150 Crew Cab pick-up truck [EET].

The danger of the two-stroke gas powered leaf blowers is not just their emission of harmful pollutants at higher levels than cars and trucks but their very act of blowing leaves rather than raking, stirs up mold, pesticides, pollutants, animal feces, pollen and mold, all harmful to our health. Some environmentalists have recommended people transition to battery driven leaf blowers. But the public health dangers from the particulates they blow into the atmosphere would argue against using them at all.

Despite hard-fought regulations in East Hampton limiting gas-powered mowers in summer months, enforcement has been lax. From April through December those gas and electric powered mowers and leaf blowers arrive like invading armies disgorging their poisonous contaminants along with maddening and unhealthy levels of noise.

The average gas-powered leaf blower pushing 300 to 700 cubic feet of air per minute at 150 to 280 MPH creates decibel levels from around 80 to 95 dB. My husband and I downloaded an app to detect decibel levels and have actually gone out into our street to measure the levels created by the use of these deafening engines on our neighbors’ lawns. Apparently, increasing numbers of people around the country have been measuring decibel levels like this as the pandemic sent more workers home to work.

It is important to remember how decibel measurements work. For example, a 20 dB sound is ten times louder than a 10 dB, a 30 dB is 100 times louder than 10 dB, etc.

The World Health Organization recommends that general daytime outdoor noise levels should not go above 55 decibels warning that sustained noise pollution can lead to a range of disorders, from high blood pressure and heart disease to depression.

We measured levels of 85 to 95 dB at 30 or more feet from the worker on different days. For workers these gas-powered leaf blowers are even more dangerous. They may generate noise levels over 105 dB at the operator’s ears.

The tranquility of our beautiful “natural” landscape is turned into a dystopian nightmare by this deafening noise and air pollution. And while there are local regulations about mower and blower noise there is liittle effort at enforcement.

The warnings about the dangerous levels of ozone pollution coming from 2-stroke engines has led dozens of communities across the U.S to ban their use in mowers and leaf blowers.

When a group of neighbors began organizing to find ways to enforce the regulations on gas leaf blowers, we discovered our ignorance about blowers in general. Scientists are now telling us that all blowers are contributing to the collapse of insect species because they disrupt and destroy their habitat — leaf litter. Using blowers in winter which is ubiquitous in our community, is destroying the over-winter hibernation and regeneration of many insects like bees and butterflies. Without these pollinators our eco-systems will collapse.

The total estimation of greenhouse gas emission from lawn care, which includes fertilizer and pesticide production, watering, mowing, leaf blowing and other lawn management practices, was found by a University of California-Irvine study to be four times greater than the amount of carbon stored by grass. In other words, our lawns produce more CO2 than they absorb.

The Financial vs. the Planetary Cost:

According to the Economic Research Service, Americans invest roughly $60 billion a year in the turfgrass industry, including lawn care products and engaging lawn care companies.

The societal cost, which seems never to be entered when looking at the cost-benefits of our landscaping practices, comes in the form of pesticides, pollutants and nitrogen found in our ground water, bays and rivers. In the air and noise pollution produced by landscaping machinery. In the form of CO2 or carbon generated in our atmosphere. In the compromising of our public health. In the contribution of lawns to ecosystem collapse. It’s a steep price.

So why are we participating in this form of suicidal landscaping?

Lawns have historically evoked prosperity, status, leisure…and conformity. Now their ubiquitous presence and culture has dulled our imaginations about how to nurture meadows with natural endemic species that attract bees, birds and animals to keep us thriving in a healthy ecosystem. How did we get here?

Manicured lawn culture was imported to North America by English and Scottish immigrants and was initially associated with wealth. “No expenditure in ornamental gardening is, to our mind, productive of so much beauty as that incurred in producing a well-kept lawn,” wrote Andrew Jackson Downing in his 1841 treatise on landscaping. Downing was the first major landscaper-philosopher in the U.S. His ideas inspired Frederik Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in in their mid-19th Century campaign to create grand parks and public spaces as well as expansive suburban estates.

When golf (another Scottish import) and lawn games like croquet and bowling (both English imports) became increasingly popular in the late 19th century, fashion dictated huge lawns. The movement was spurred by the invention of the lawn mower in the 1830s. By the 1920s, gas-powered mowers gave the bourgeois lawn craze a boost. A grand lawn was about status.

But it was after the Second World War when, in both Canada and the U.S, government backed loans for affordable houses would lead to exploding suburbs where the feature of each yard was lawn.

“No single feature of a suburban residential community contributes as much to the charm and beauty of the individual home and the locality as well-kept lawns,” opined Abraham Levitt, the visionary behind Levittown, the model working class American suburb.

Levitt saw his grass lawn concept as part of a plan that promoted responsibility in keeping a clean yard. Neatness and order led to respectability.

The original Levittown owners agreed to mow their lawns once a week between April 15th and November 15th. In some planned communities across the country, written regulations determined lawn length and orderliness. Lawn culture as we as we have come to know it was imposed on the suburban landscape.

In most North American suburbs, the pressure to maintain a perfectly coiffed lawn was simply accepted, endorsing a strict code of conformity. A kind of citizenship. I know. I grew up in a working- and middle-class suburb in western Canada in the 1950s where every Saturday the sound of lawn mowers announced the weekend. Mowers, fertilizers, sod and seeds were easy to attain. Crab grass and dandelions became our enemies. Conformity, respectability, and order, our goal.

And as lawns have become more ubiquitous, they have become more policed. Legal prescriptions of conformity are written into the codes of counties and homeowners associations all across the U.S. Take for example the county code of Fairfax, Virginia, stating that “it is unlawful for any owner of any occupied residential lot or parcel which is less than one-half acre (21,780 square feet) to permit the growth of any grass or lawn area to reach more than twelve (12) inches in height/length.”

Roman Mars in a 99% Invisible podcast focused on stories about lawn enforcement agents around the country who have fined or even sent to jail homeowners for keeping a shoddy lawn. One story told of Joe Prudente, a Long Islander who had retired to Florida. He ended up in Pasco County jail in 2008 for “failing to properly maintain his lawn to community standards.” Joe explains that he had tried several times to re-sod and seed his lawn, but it kept turning brown and patchy. And his story is not unique.

In 2019, a Dunedin, Florida man sued his local town administration because the Dunedin Code Enforcement Board had threatened to foreclose on his house after his lawn grew beyond 10 inches. The fines for this malfeasance had accumulated beyond his ability to pay.

It’s as if a prescribed lawn—specified height and density, weedless and color conforming—is a moral force for the good of American and Canadian civilization. I can almost hear my Canadian Protestant grandmother exhorting: Cleanliness is next to Godliness! You could say the imposition of the lawn on the North American landscape was a Protestant ethical plot.

Yet if we look at the grasses that have been nurtured for North American lawns, we are looking at foreign species—Kentucky Blues originally from Europe and northern Asia, Bermudas from Africa and Zoysias originally from East Asia. And as any number of critics have pointed out, while these grasses survive here, they cannot thrive without massive intervention which is where all those fertilizers, pesticides and water come in.

Yet as Roman Mars points out in his podcast, we “don’t let grass get tall enough to go to seed, but we also water and fertilize it to keep it from going dormant. We don’t let it die but we also don’t let it reproduce.”

In his New York Times article Why Mow? The Case Against Lawns, Michael Pollan puts it this way: “Lawns are nature purged of sex and death. No wonder Americans like them so much.”

The Anti-Lawn Movement or Lawn Shaming

You could say information to fuel the anti-Lawn movement has been around since 1962 when Rachel Carson’s explosive book, Silent Spring transformed our consciousness. When I got swept up in the environmental movement a few years later, I began shaming my mother in Vancouver, Canada about keeping a “bourgeois” lawn.

For the last thirty years article after article has laid out the facts about fertilizers, pesticides, water consumption and lawn machines. We have had all of this cautionary information, yet despite drought and the extreme weather events we are experiencing, the poisoning of our waters, the increasing collapse of species…despite all this, the lawn is still everywhere!

In 2015 efforts at lawn shaming in California emerged when water shortages from the drought were felt dramatically. Restrictions on watering, hefty fines, neighbors reporting on neighbors and the shaming of fancy hotels, celebrities and wealthier water guzzlers maintaining lush lawns produced its own hashtag #droughtshaming. But even that movement seemed to fizzle.

Time to Decolonize the Yard:

In Canada a different critique has surfaced whereby environmentalists together with First Nation Leaders and some gardeners are taking a historical view and seeing the lawn as a vestige of colonialism.

“It is, they argue, a lasting symbol of how settlers appropriated Indigenous land and culture,” writes Sierra Bein for the Toronto Globe & Mail, “and the rigid Western ideal we have imposed continues to hurt the planet and, in turn, all of us.” For Bein, in her article Is It Time to Decolonize your Lawn, “a backyard with a big lawn is like a classroom for colonialism and environmental hostility.” The rise of the lawn, she continues, “meant a decline in the biodiversity so relied on by Indigenous people.”

If the lawn is an effort to control nature, this argument goes, it needs to be decolonized and looking at indigenous practices is a way out.

What Can You-We Do?

Where I live on Long Island the contribution of lawns to the collapse of our planet’s ecosystems is a consciousness that has barely taken hold. Yet, when panicky people increasingly ask what can I do today that will help to hold off further climate change, perhaps you/we can begin by taking a hard look at our lawns. Sooner rather than later.

Clearly, we need to act both individually and collectively to tackle the formidable task of halting climate change.

As individuals we can…

Transform our lawns into meadows with native trees, plants and wildflowers that can sustain bees, butterflies, insects and bird life. First, we need to stop fertilizing, pesticiding, watering and cutting our lawns. We can either remove non-native grasses or smother them with cardboard and mulch to grow native plants. If you need help, hire those who can assist you to maintain a meadow. Encourage change in the landscaping industry by hiring those who think about whole ecosystems, those who can help you identify endemic species that birds, bees and butterflies need.

Re-imagining our landscaping aesthetics. Chaos can be beautiful

A gardener friend reminds me that a meadow is so much more beautiful than a lawn. It is everchanging constantly bringing new pleasures. On Long Island the Perfect Earth Project site advises on alternative landscape practices. Another group called Rewild Long Island encourages and advises on biodiverse landscaping practices. Another website/organization on Eastern Long Island advocates and advises on landscaping that restores birdlife, called 2/3 For the Birds.

You can also turn your yard into an edible garden with fruit trees, berries, vegetables, and herbs. There’s a group called Fleet Farming with a great website showing how you can transform lawns into lusty veggie gardens. The group Edible Estates founded by Fritz Haeg, an architect and artist, guides you in ripping up your lawn and replacing it with aesthetically exciting edible plants.

Then think through whether you need any space for a small lawn to put out a picnic table or for the kids to play. Even that small lawn can become clover or moss or Buffalo grass, native to North America.

Rain Gardens to Prevent to Halt Toxic Run-off

In Puget Sound and Seattle there are now almost 12,000 rain-gardens replacing lawns. My environmental activist friend, Sidney Beaumont, reports that he and many others have re-jiggered their gutters to direct rain water from the roofs onto a depressed special garden containing native plants, rocks and bio-retention soil that absorb all that rain, rather than produce run-off to the streets which becomes toxic by the time it reaches local waters. It is part of an effort to protect stressed salmon populations. It’s all connected!

Designing boulevards without lawns in Seattle by creating depressed gardens with natiive species that use stormwater to prevent toxic runoff from reaching the ocean and salmon.

Real Change Requires Collective Action

Increasingly we live in an atomized and polarized world where it seems to be more difficult to reach out with common purpose to our neighbors. But we need to find a way to do exactly that as a first step. To talk to neighbors about this issue, about what we can do to reclaim the natural world. It often takes the initiative and drive of a couple of neighbors, but we are in this process in our neighborhood.

We are also encouraging letters to the editor at our local newspaper. (We are lucky we still have a local newspaper in our town.) In those letters we provide links to websites like the American Green Zone Alliance that educates about healthy yards, communities, workers, and planet. We recommend James Fallows’ excellent 2019 chronicle in The Atlantic describing the community process of organizing to change the laws on gas-powered leaf blowers in his city, Washington, D.C.

Locally we are inspired by the rebate program at Peconic Estuary Partnership whereby those who live within the Peconic Estuary watershed can receive a $500 rebate to grow native plants. Nationally we’re animated by the work of renowned entomologist, Doug Tallamy’s, Home Grown National Park movement that encourages everyone to cut their lawn size in half to grow native trees, shrub and plants.

A group of our neighbors and East Hampton residents formed an organization, Changehampton, to elaborate a ‘Call to Action” through an e-pamphlet now available on our website. In a presentation to the East Hampton Town Board in May, 2022, Changehampton, proposed a 3,000 sq. ft. community native and pollinator garden to be created directly in front of Town Hall as a launching of a Pollinator Pathway in our community. The pollinator garden can be a means to inform our community about the effects of lawn culture on our environment and health. And about the alternatives.

In July of 2022, ChangeHampton also presented a proposal for a massive education campaign to the East Hampton Town Trustees, that would link what happens ins our yards to the health of our watershed, aquifer and bays along wiith aquatic life. Our work continues to explore ways to convince more residents and Town officials to include restorative landscaping, non-toxic, bio-diverse, regenerative landscaping in all of our plans for public spaces.

All of these efforts point towards meeting with our elected representatives at the Town, County and State level. We need to begin supporting candidates who will take on our mission. The clock is ticking. Finally, we need to work with our local reps to write new legislation and regulations that include enforcement. Many regulations currently in place are not working. This is the way we build a movement and make changes that are healthier for the planet which we inhabit.

Finally, we must ask ourselves: Can we imagine a different landscape that is welcoming to birds, bees, butterflies and insects that we desperately need to survive? Can we reclaim the quiet that once attracted us to this very place? Can we halt the train wreck of climate change and species collapse that is upon us?

* * *