“I’ve got something special for you, “ Nicole’s voice teased through the telephone.

The word “special” from Nicole (her name and those of her family are changed here) conjures up everything from the kitschy to the magical and luscious. I’ve known Nicole and her houseful of extended family for eight years. We’ve spent Christmas, New Year’s and Easter together, as well as sporadic Saturday afternoons on Nicole’s Haitian island in Flatbush.

I’ve also been a guest at their birthday parties. Not the kind where everyone sings “How old are you, now?” – in Nicole’s house birthday parties are for the spirits, like Ogoun, Dumballah, or Papa Zaka, major personalities in the Vodou pantheon. Although Nicole is initiated as a Manbo, a Vodou priestess, she usually acts as a deaconess to her mother, Therese, who come from a long line of Manbos and provides the ethical and emotional ballast for a flock of intimate friends and family in Brooklyn. Yeah, “special” means more from Nicole than from just about anyone else.

“I’ve got videotapes from Haiti,” Nicole oozed seduction through the receiver. Now I was disappointed. Several Haitian cab drivers around town had already offered me deals on video tapes of the demonstrations and celebrations after Jean-Claude Duvalier left. Since I had been in Haiti during that first post-Duvalier month, I was not too interested. But curious all the same.

“This tape’s called Dechouke,” Nicole was giggling. Dechouke is a Creole word used in Vodou songs that has been resurrected and given new life in the upheaval of recent history. It means “uprooting” or “complete change,” and has become a catchword for the popular revolution, referring to everything from kicking out Jean-Claude to looting the houses of big Tonton Makout (the new government’s official Creole spelling of “Macoutes”).

“Oh honey, you’re gonna love it!” Nicole explodes, “I think you should come right over to see it, ‘cause even though it’s called Dechouke, I call it Makout Griyo.” I wasn’t prepared for that special. Makout is shorthand for Tonton Makout and griyo (griot, in the old spelling) is a tradition-packed word for “barbecue.” Nicole’s tape is a home video of a Tonton Makout being burned alive.

From Miami to Montreal, Haitians are circulating these tapes. And like everything else in this often insular community they are being turned into a “little business.” At Ma Maison, a Haitian record store on Nostrand Avenue kitt-corner form the Dieu Si Bon (God So Good) restaurant, monthly newsreel tapes of events in Haiti sell for as much as $40.

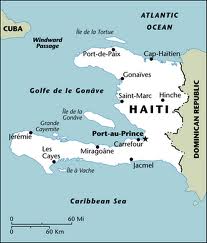

Although several French newspapers and Creole radio programs serve New York’s Haitian community – the largest enclave outside Haiti – the main means of getting information from “home” has been word of mouth. Partly this has to do with repression, which breeds elaborate humann networks of information, partly with literacy and language. Haiti is till an oral culture. The means of communication may have been upgraded recently, but the distribution network is still operating. Turning the videos into a “little business” is also rooted in the conditions of Haiti and New York, where survival requires constant invention.

Some “little businesses” in the Haitian community are risky and expensive, like “making papers” – social security, driver’s licenses, or green cards. But others are innocent, like the borlet, or borlette (Haitian numbers), or the tap-tap that cruise the main avenue of Flatbush. In Haiti tap-tap are the brilliantly painted trucks that serve as public transportation. Along Church Avenue, past the signs for jerk chicken, hot rotis, ad goat’s meat, near Chez Ben’s discount store, and along past the stands filled with salty cod and yucca tap-tap are private cars that load up with frustrated people at bus stops.

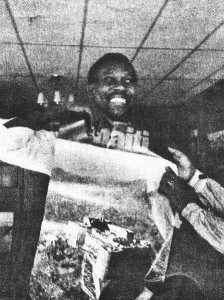

These days the tap-tap and Haitian-driven yellow cabs are flashing signs of change – ‘I love Haiti” bumper stickers. “They’re a symbol of the pride that Haitians feel for the first time after years of taking a bum rap,” says Raymond Joseph, editor of one of New York’s French language newspapers, Haiti Observateur. Joseph explains that beyond the racism and discrimination against the foreign-sounding, Haitians have suffered from the media image of them as a soruce of AIDS, as unwanted boat people, and as practitioners of the world’s least understood religion – Vodou.

But the biggest indicator of change in the Haitian community can be felt right at Ma Maison. While the teenagers swivel their hips to the kompa (compas) and meringues of Haiti’s top bands like Coupe Cloue and Tabou Combo, the older men are arguing politics. Talking freely about politics is blowing fresh energy through the Haitian neighborhoods, spilling out onto street corners from restaurants and bakeries ,…and sooner or later they all turn to the question: To Go Back or Not to Go Back?

This existential question is buzzing the crowd at La Detente, a huge, middle-class Haitian restaurant and lounge in Jackson Heights, Queens. It’s Saturday night and the faint sounds of a restrained Cuban combo drift downstairs to a reception room filled with the cream of the Haitian professional class: doctors, lawyers, architects, engineers, social workers and community activists. Some of their wives in padded shoulders, carefully painted fingernails and perfectly groomed upsweeps feign the slightly bored visage of the upper-class Haitian lady. In this room, choking on the propriety of the Haitian bourgeoisie, we are waiting for the guest of honor, Jean Dupuy. Dupuy is going back.

When he enters, the infectiously warm and gregarious Dupuy animates the crowd with kisses, hugs an handshakes. Whipping out his instamatic, he arranges far-flung members of his family with professional associates; he introduces people while snapping away, his roly-poly body in constant motion.

Dupuy came from Haiti 23 years ago. He was mayor of Gonaive when Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier won the presidential election. A few years later Dupuy checked into the Columbian Embassy in Port-au-Prince, and in 1963, after five months of asylum, he left for New York.

At first like millions of other foreign-speaking immigrants with skills or civic experience in an underdeveloped country, Dupuy could get only low-paid, menial work. First, he packed boxes for a department store. Then he worked the docks at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Watching thousands of Haitians stream into New York during the late 1960s, fleeing Duvalier’s Tonton Makout, Dupuy saw a need. He helped found the first Haitian social service center and has been its director since 1968.

In contrast to the dreary institutional grays and greens of other family service centers, Dupuy’s offices on Manhattan’s Upper West Side are painted the colors of lemons, green plantains, and hibiscus. Tacked to the wall behind his file-buried desk are color prints of Haiti’s four slave generals who led the revolution to create the first black republic in the world. Alongside the generals is a big map of the New York subway system.

The first people to flee Papa Doc’s terror in the late 50s and early 60s were upper-middle-class politicians and professionals, followed by shop-keepers, teachers and skilled workers. By the 1970s the mix fleeing Haiti for New York included more and more peasants and unskilled workers. Dupuy’s center has eased the way. On a miniscule budget, it has found thousands of Haitians jobs as domestics and factory workers, helped them get visas, and provided English and high school equivalency classes, job skill training, and legal counseling.

The phone rings constantly. In between calls Dupuy explains that he is also a family counselor. “There is so much strain on the family here. Haitian men do not believe in the right of the wife. The wife is for cooking and taking care of children. Here the wife wants to work. As Dupuy’s English slips into a mixture of French and African grammar, the root of Creole, I am reflecting about how many women in Haiti work from sunup to sundown and then some and how much of this image of the male provider is an ‘aspire to’ model, much as it was here until recently. In Haiti, it’s a model that differentiates the urban from the rural, the city slicker from the peasant. But even in the cities women work outside if they can get a job. Perhaps most men who come to The Promised Land hope for that model and suffer shock when they find out that given a chance, most wives don’t want it.

I’m reminded of a Haitian taxi driver story (with an estimated 30 percent of New York’s cab drivers being Haitian, who hasn’t got one?): My driver is talking about going back to Haiti for a visit; this time he’s going to bring back a wife. “What?” I ask, “no prospective wives in New York?” He tells me that he had one, put her through nursing-school, and the day she graduated she left a note on their bed saying ‘goodbye’.

Soulfully, the driver says he has learned something about love in the process. He tells me the story of “azoozal” love. “Don’t you know about “azoozal” love?” he asks, dumbfounded that I look dumbfounded. He then patiently explains. There are three kinds of love. Romantic love is whenever you go and put all that pretty make-up on and nice clothes, and look good “Anybody could fall in love with you ’cause you look so good, but without those things I might not like you so much.” Then there’s platonic love. “You and me we grew up next door together; I do a favor for you, you do a favor for me. Maybe we were classmates. You know. We’re good friends. But no sex.” Then there’s “azoozal” love. That’s when you really know somebody. “Maybe you work together and you know each other through happy times and sad times, you help each other. It’s sex, too.” Sure I understand, but “azoozal”? He repeats it several times until I get it. “As usual” love. And I don’t know anymore whether this is a story about love or language. But I’m thinking that one of the great fortunes of this immigrant city is the playfulness forced on English.

Because Dupuy is packing as much music as possible into his English as he describes the conflict in families here, not only between husbands and wives but between parents and children. In Haiti parents are strict authoritarians; children must obey. Here the leniency of American culture creates painful tensions. The immigrant experience repeats itself.

Dupuy, referring to his community as “brothers and sisters,” has played “Big Daddy’ for his family – a lovable helmsman, steering poor Haitians through the rocky terrain of legalization and adaptation to America. Now, at 68, fulfilling the dream of many in his “family” he’s going back to Haiti to retire. Well, not exactly retire. He’s going to build a house on 160 acres in a remote rural area and farm – “agriculture mixed” he beams in a fusion of English and French.

But if Dupuy is returning to a quiet life in Haiti, Father William Smarth, a Haitian priest exiled by Duvalier in 1969, plans to return to a bitter conflict within Haiti’s Catholic Church. Smarth is thin and gentle, with long slender hands and fingers; he doesn’t look like much of a fighter. His face, constantly expanding with laughter, gives him the appearance of a mischievous gnome rather than a weathered trooper.

With Father Antoine Adrien, another exiled priest, Smarth came in 1971 at the invitation of the Diocese of Brooklyn. While middle-class Haitians were becoming Americanized in Queens, the poorer, newer arrivals were pouring into Crown Heights, Flatbush, and East New York, and there were only two Haitian priests to minister to their needs.

“We wanted to live in a regular house to work with the people,” Smarth says in his carefully articulated English filled with the round vowels of Creole. “But the Diocese refused, and we had to live in a rectory for three years.” His face breaks into soft laughter as he explains the significance: rectories have strict rules about hours and bureaucratic formalities. “For Haitians this is impossible. We needed to have a center where they could feel free to come any time, with any problem.”

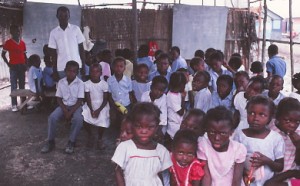

In 1977 Adrian and Smarth moved to a small brick building on a devastated block in Crown Heights. And as they predicted, Haitians began coming at all hours. “Sometimes at 2 a.m. And we were spending all day at the INS offices, sometimes just for one case. Then we accompanied frightened new arrivals to the hospital. In emergencies they came for money.” To coordinate their work, they opened the Charlemagne Perault Center in the basement, with the help of two French priests. “It was especially for the refugees, for undocumented people, Smarth adds. During the heaviest years of the boat people (1980-84), the Charlemagne Peralte Center became a safe haven at the end of a long, perilous journey.

The donated furnishings in the priests’ home and center create a lackluster functional aesthetic, except for several Haitian paintings. One in particular captures the tension of the refugee experience. A peasant mother, hair in bandanna-the insignia of her class – stands in the foreground holding an infant in her arms. A silhouette of a simple over-packed boat is in the background. The painting makes me want to cry. But I suspect the artist intends hope.

“When refugees arrived, the center was the first place they would go,” says Joseph Etienne, who heads a coalition of Haitian community centers and helped the priests open the Charlemagne Peralte Center.

“The name was a signifier,” Etienne claims. “Peralte was a true Haitian nationalist, symbolizing integrity, honesty and a deep concern for his fellow citizens.” In 1918, Peralte led a peasant uprising against the U.S occupation of Haiti. The Marines assassinated him the following year and, as a lesson to Haitians, nailed his body to the door of the police headquarters in Cap-Haitien. That image has stuck in the Haitian psyche.

“Nobody wanted to even recognize the refugee problem when Smarth and Adrien began working here” Etienne adds. Surrounded by a community distancing itself from the media image of “pathetic” boat people and fearful of speaking out against the Duvalier regime because of the repercussions for relatives back home, the priests worked with Haitian leftist and exile organizations as well as human rights lawyers to educate congressional committees in Washington about the political realities of Duvalierism and the plight of the refugee community here.

Father Smarth became embroiled in another controversial issue by conducting mass in Creole and generally promoting Creole, rather than French, as the true national language. In Haiti, French is the official language, the currency of politics, law, the media, education and until very recently, the church. “French is the language of success,” says Smarth, “spoken by only about 20 per cent of the people. Creole is the popular language, spoken by everyone.”

When Haitian parents delivered their kids to their new schools in Brooklyn they said their children spoke French. But French-speaking teachers quickly discovered they didn’t. Although composed largely, but not exclusively, of French vocabulary, Creole is West African in grammar, rhythm, and sound. By fighting for Creole, the priests were raising complex questions about culture and class. French culture has always defined the aspirations of the Haitian elite, who often sent their children to study in Paris. West African culture defines the world of the peasant. Urban working-class people see French as a way up and a means of distinguishing themselves from the peasant. These cultural pretensions were transported to the New York community, where Haitians also learned that identifying themselves as French might help them escape the low social status of American blacks.

The Brooklyn priests, working from a liberation theology perspective, saw language as part of a larger cultural identification with their West African heritage, a symbol of their pride, a means of unifying opposition to the Duvalier regime and to foreign domination – French and American. Smarth wrote Creole liturgies calling for freedom, human right, equality and justice and sent them back to Haiti, where a new, socially active church was emerging. In post-Duvalier Haiti the progressive sector of the church is supporting a grass-roots democratic movement. But conservatives in the hierarchy remain, those who not only refused to denounce the Duvalier regime, but often supported it. Fathers Smarth and Adrien are returning to that battleground.

“The people who are going back, the exile, they are professionals. They’ll have jobs in Haiti. We can’t go back,” whispers Serge as we sit on his bed in a darkened room in Flatbush. The wiring in the overhead light is broken and the super will not come to fix it. As illegals, Serge and his roommates will not complain.

“The people who are going back, the exile, they are professionals. They’ll have jobs in Haiti. We can’t go back,” whispers Serge as we sit on his bed in a darkened room in Flatbush. The wiring in the overhead light is broken and the super will not come to fix it. As illegals, Serge and his roommates will not complain.

His brother, Franz, is stretched across the other bed trying to follow our conversation. He arrived from Haiti a year ago. Georgette, their sister, is creating wonderful Creole aromas in the little kitchen. A cousin, Max, also lives with them in this two-room apartment in a neglected building filled with Haitians.

“If we had even a little money we would rather be back home,” Serge continues in a slow and careful English. “We prefer the lifestyle back home. We don’t like it here. But we can’t leave. We came here to survive our lives.” These last words echo what I’ve heard from other undocumented Haitians who have come during the past decade after years of corruption had strangled the Haitian economy.

Serge, like many others, has sacrificed an outdoor, gracefully paced tropical life with a heavily branched family tree in a small rural town surrounded by sugar cane, to live in a brick jungle in Brooklyn. He is caught between cultures and possibilities; if he longs for the tempos and tastes of life back home, he also remembers the hopelessness of a stagnant and corrupt system. Here though exhausted from his long commute to and from a factory job, he talks of getting his high school equivalency, then studying business administration. Possibilities.

It’s above all the possibility of education particularly for their children, that make Haitian immigrants eager and reliable workers. I think, for instance, of the Blanchard family on Washington avenue in Flatbush: since they arrived 25 years ago, Mrs. Blanchard, a babysitter and her husband, a security guard, have shepherded nine children through college and professional degrees. But there are other reasons why Haitians are riveted to their jobs here. As with millions of other immigrants, the jobs in Serge’s household – in factories, restaurants and private homes – are vital not only for their survival but also for their families back home. Serge helps other family members immigrate and he sends money home to his grandmother, mother and six brothers and sisters in Croix-des-Bouquets, a small town about 20 minutes outside Port-au-Prince.

“It is this responsibility to the families back home that creates an often debilitating psychological stress on Haitians here,” says Roosevelt Clerisme, one of the few Haitian psychiatrists (out of 20 in New York) to set up a practice in Brooklyn. “And for many Haitians there is the disillusionment that comes with finding out how difficult it is here, where they don’t have their extended families to buffer them.” For the approximately 150,000 Haitian illegals in the city, there is the added problem of “paranoia, because they constantly fear that the INS or bosses, landlords, or officials will find them out. Or that if they have a dispute with a friend or neighbor they will be reported.”

As Serge walks me back to the subway stop after dark, lingering to see that I get on the train, he tells me about some trouble in his building. “Two Puerto Ricans who live here are always picking fights with the Haitians.” Last night Serge explains, the super, also Hispanic, went to his apartment to get a gun when a fight broke out in the hallway. Eventually the police came and arrested both the super and one of the Haitians. This situation, terrifying for anyone, is worse for the building of illegals, since any trouble with the police threatens their future here.

Now a new source of psychological stress is invading the community. “Depression is on the increase” says Lola Poisson a Public Health graduate from NYU who has set up the first Haitian medical referral service on Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights. A feminist with an expansive sense of public health, Poisson accompanies Haitian housewives on outings to museums and libraries on Saturday afternoons and conducts weekly workshops for school children to help them with their identify problems as Haitians. She believes that the already considerable strain of immigration is compounded by the complex decision about going back home. “They may want to go back, but cannot.”

“Families will break up over the decision to stay or go,” says Joseph Etienne. “Now people realize they cannot just pack up and leave. We have jobs, homes, children in school. There is the uncertainty of things in Haiti, no jobs, the economy is worse than ever. So for the person who has been dreaming of going back, this creates problems. And many families will divide The next few years will be very difficult.”

The energetic and rapid-talking Etienne counsels families about this situation on one of the weekly Creole radio programs in the city. “I try to let them know that there are ways they can contribute without moving back,” says Etienne, who talks as if he’s got a mouth full of mashed plantains. “The important thing is that we keep working to make Haiti a free and democratic country so we can visit.”

The fact that Haitians have always dreamed about going back makes Joseph Etienne’s job as director of a coalition of neighborhood service centers very tough. “We are neglected by most of the agencies, by the city,” says Etienne. “The reason is simple: We don’t have political power. We’re insignificant because Haitians always said they’d go back when Duvalier was overthrown.”

Haitians in New York have seldom united as a whole community, whether dealing with the situation in Haiti or seeking recognition as an ethnic group here. The earliest arrivals in the ‘50s , while sharing a common opposition to Papa Doc, were bitter opponents; their animosities inhibited unified effort. In the ‘60s, socially conscious Haitians who discovered they were identified more by skin color than by National origin, worked within black American organizations and participated in the civil rights movement. During the War on Poverty, some, like Dupuy and Etienne, established federally funded service centers and programs in the community.

“But,” says Etienne, the words tumbling out of his mouth, “it has been a political battle to negotiate to get funds, to prove our ability to handle public funds and manage programs. There are almost 400,000 Haitians in the New York area and we don’t have a health program. There is no senior citizens’ center. There are 40,000 Haitian kids in schools in Brooklyn and only one after-school program!” Even though there are strong class and political differences that divide Haitians, Etienne believes that most Haitians shun politics because of their past experiences in Haiti.

Despite the obstacles, by the late ‘70s, and early ‘80s, the refugee issue and the Creole campaign spearheaded by the Haitian Fathers and the political left created the condition for some unified action. In December, 1981, approximately 10,000 Haitians marched in Washington to demand the release of Haitians from immigration detention centers. In January another 5,000 marched down Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn with the same demand. Creole became the language of meetings and public speechmaking.

Then came the idea for a fire truck. Several years ago, Haitians here began organizing themselves according to the towns they came from. Concerned with the desperate economic conditions and the corrupt handling of international aid and inspired by the rising opposition movement to Duvalier, they began fund-raising in the community here to provide specific items for their towns back home. It began with a fire truck for Gonaive. Then, through dances and raffles money was raised for an ambulance. According to Jean Charles, associate director of student activities at City College, there are now about 20 such groups acquiring equipment and materials for Haitian schools and hospitals. This year Charles raised $15,000 from Episcopal Church for his home town of Grande-Riviere-du-Nord. “It doesn’t sound like much, but it goes a long way in Haiti,” says the 40-year-old Charles, who once worked at Jean Dupuy’s family service center. “The money will create self-employment programs, leadership training for young people in literacy and reforestation. It also includes money for the local school and library.”

Like Charles, Dupuy, and Smarth, Joseph Etienne has also gone back to visit his home town since Duvalier left. And like many others, it was his first visit in 20 years. The stocky, round-faced Etienne left Haiti in 1966 to study in Europe where together with other Haitian students he was swept up in the radical movement. “It was a rapid political education for us – why the students lost, how the unions were better organized – and we wanted to see how we could apply those strategies we learnt in Haiti.”

Papa Doc, suspecting that Haitians studying abroad during those year were all Marxists, refused to let them return. Some who tried were arrested. Simultaneously, Duvalier’s police were attacking student organizations in Haiti. Etienne came to New York in 1970 and immediately went to work as a community organizer, first at St. Theresa’s Church. He became director of the coalition of Haitian centers in 1982. A photograph of him with Jesse Jackson stands behind his desk.

When Etienne returned to Haiti this spring, he went to “offer assistance, to help, to see what services were needed.” What he found shocked him. “Not only me but others like me who have gone back with the idea that we were going to be saviors…we learned something new.” What he and the others learned was that the people in the countryside are actively organizing. “Everyone is participating in decisions about rural development,” says Etienne with excitement, “the old, the young, men and women. Women’s involvement, perhaps shocked me the most. And what interested me was that kids who had gone off to a larger town or to Port-au-Prince to school, but were unable to find jobs, returned to their villages and were helping the older people analyze their problems. The young people are also helping with the Catholic Church’s literacy campaign.”

When Etienne returned to his village, Fonds-des-Negres, in southern Haiti, the local residents organized a meeting to explain that their primary needs were water, electricity, and a school. They told Etienne, “We are hungry, but we don’t want charity. We don’t need those old clothes that people send here, because that competes with our tailors. What we want is sewing machines to set up a sewing cooperative.”

Local peasants wanted to know if Etienne could help them find an agronomist who could show them how to crossbreed two strains of lemon. “We weren’t prepared for that kind of clarity” says Etienne, still looking surprised. “We aren’t learning about that in the press here.”

“Most Haitians are less interested in the presidential elections, in big government, than they are in solving the unemployment problem, in figuring out a way to develop their local economies,” says Lionel Legros, who teaches science in Creole and English to Haitian children at Walt Whitman Junior High School in Brooklyn, and has a weekly Creole radio program on WKCR. Legros explains that decentralization is a major demand in the provinces where people have watched their villages die and children starve while services, wealth and power concentrated in Port-au-Prince.

For the 38 year-old Legros, who cut his political teeth on the radical student movement at Columbia, a grass-root democratic movement in Haiti is a dream come true. When he went to visit Haiti this spring, his first visit since boyhood, he got sick the first day: “I guess it was just so overwhelming.”

Legros also works one night a week at the leftist Haitian Information Center. Its small office above a furniture store on Flatbush Avenue is crowded with dog-eared papers and books. One wall is covered with posters protesting the Duvalier regime, another wall is devoted to images of Charlemagne Peraulte.

For years, the news from Haiti — about oppositional organizing, problems, abuses by the regime – had to be smuggled out. “The center has always been an antenna for things happening in Haiti,” Legros claims. Some of the information would turn up in his early Sunday morning radio program. Recently, after nine year of producing the show, Legros has been getting pressure from the station’s management, which claims it has received threats of lawsuits and even bombs because of political opinions and personal attacks aired on the program. More recently, Haiti Observateur editor, Raymond Joseph, protested to the station when Legros called him “an enemy of the Haitian people.” Legros does not deny making the statement after Joseph publicly accused a Haitian professor of being a Communist and advocating violent revolution in Haiti. He claims he invited Joseph on the show afterward. WKCR’s management is concerned about FCC guidelines and the fact that it cannot monitor the Haitian program because it’s in Creole. Similar concerns led to the cancellation of six days a week of Creole programming on WNYE, the Medgar Evers College station, this spring. The management, alerted that political attacks against rivals in the community were taking place, stipulated that producers must broadcast in English and pay more for the use of station facilities. The Haitian community was the loser.

The bitter attacks and disputes in the community, says Legros, have to do with “who is going to have influence in the Haitian diaspora in New York. This is after all, the most important community outside Haiti – and it is economically and politically important to Haiti.”

But political accusations are not restricted to radio programs. Raymond Joseph, who has published Haiti Observateur with his brother, Leo, for 16 years, says he is often the target of attack by New York’s other Haitian papers, Haiti Progres and Horizon d’Haiti. “They constantly accuse me of being a CIA agent, of taking CIA money,” sighs the ebullient and elf-sized Joseph. Back in the ‘60s, the Josephs started a shortwave radio station to broadcast to Haiti. Like many other Haitian oppositional groups, they got some help from the Johnson administration, which had continued the efforts begun under Kennedy to destabilize Duvalier. When asked whether there was any CIA backing involved, Joseph says, “I didn’t check where the money came from.”

Lionel Legros says leftists in the community here disassociated themselves from all the CIA backed invasion schemes. “On my show I have always argued that the Haitian people will overthow Duvalier. Raymond Joseph is always promoting a presidential solution and defending American policy in Haiti.”

Raymond Joseph describes himself as a centrist. “I have always believed in coalitions – excluding the Communists. And the newspaper takes a center position.” For several years Joseph has worked with the Haitian Committee for Unity, an umbrella organization that formed to promote municipal, legislative and presidential elections in Haiti. Several of it prominent members have returned to Haiti to run for president, but Joseph doesn’t think any of the candidates so far have the right stuff. “Some are only popular in New York,” says Joseph, raising his eyebrows and smiling. “In Haiti most people are more interested in jobs, in improving agriculture, education and health care.”

Haitians have also continued to protest against the Duvalierist junta, which has been reluctant to cooperate with civic, church and trade-union leaders. Joseph is more concerned about how the center will hold, “given the activity on both the right and the left. It’ a big job for people in the center to try to control what’s going on and try to steer Haiti toward a democratic future. The Communists see us as a menace,” says Joseph. “The Communists back Haiti Progres.”

The offices of the leftist Haiti Progres are a couple of blocks from the Haitian Information Center on Flatbush, but, says Legros, “We keep out distance. We know what each other are doing. We just can’t work together.” Legros is reluctant to explain whether it’s a conflict of style, substance or both.

Haiti Progres claims a circulation of 40,000 and, like Haiti Observateur, has just opened offices in Haiti. Its articles and editorials reflect the acute intelligence of its editor, Ben Dupuy. On a Wednesday afternoon, the mostly white staff is putting the paper to bed. The suave-looking Dupuy dressed in a beige tropical suit the same color as his skin, makes me a coffee on the espresso machine and proceeds to interview the interviewer.

Dupuy won’t talk unless he knows my perspective. Perspective? I don’t know I’m just trying to find some things out about the community here, its response to events in Haiti. Since he’s an editor of one of the two leading newspapers, I want to know what concerns him. This is going nowhere. Dupuy delivers a lecture on the myth of objective journalism. The importance of perspective, of position. I’m disgusted, not at him but at myself. Because I have given that same lecture in classrooms to captive students. Did they feel the way I do now? I repent. Not that I don’t’ agree with him. It’s the delivery – accusatory, judgmental, self-righteous.

Dupuy still demands my perspective. Okay, okay, I went to Haiti after Duvalier left, to write about liberation theology I’m not Catholic or religious, but I’m sympathetic to the progressive work of the church and the grass-roots movement in Haiti and think more reporters ought to be writing about it.

Dupuy asks me again what my perspective is on this piece, and I repeat what I said before. He looks away. He has given up on my perspective and starts explaining carefully, methodically, the quagmire of U.S AID, IMF and World Bank policy in Haiti.

“The real issue is independence” says Dupuy, who argues that the U.S. wants to determine Haiti’s economic direction to ensure a cheap manufacturing facility and a market for American goods. “The fear of communism as a rationale for supporting the junta is a smokescreen,” he says. In the service of that fear, the U.S. has been giving Haiti $54 million annually. In February of this year, AID proposed an additional $21.7 million; $10 million of it just went to the junta. In addition, the Haitian government has received $6 million in military aid since Duvalier left, “assistance” that Haitians both here and in Haiti have protested “The real concern is control,” Dupuy insists.

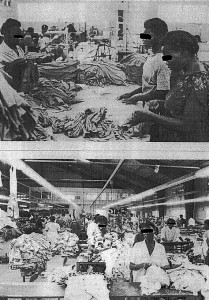

In 1981, U.S. AID and the World Bank outlined a plan for Haiti’s industrial development that has resulted in a concentration of over 300 mostly American –owned companies near Port-au-Prince’s airport, assembling imported materials for export to the American market. Salaries are approximately $3 a day. Since Duvalier left, workers at those plants have been striking and demanding trade unions, higher wages and improved social services. The World Bank strategy opposes unions, benefits and services. “The only ones who profit are the factory owners,” claims Dupuy, who believes the overall scheme, like that outlined for other Latin American countries, promotes austerity and stifles indigenous development to make interest payments to the banks.

As in Latin America, those sympathetic with liberation theology in Haiti are also critical of the American plan that treats people as statistics and focuses on GNP rather than distribution of wealth or local development. “We want to determine our own way,” says Father Smarth. “The U.S is looking for greater dependency.”

Dupuy produces a U.S. AID Action Plan drawn up in February after Duvalier’s departure. Among other things it calls for the dismantling of the country’s food, oil and sugar companies, nationalized industries, while simultaneously calling for reduced tariffs on imports. To Dupuy, this can only lead to further ruination of Haiti’s economy, and total dependence on the U.S: “It destroys the indigenous agricultural industry as does the donation of food by U.S. AID” Dupuy sees more and more Haitians comprehending this process. During a recent storm, when U.S. AID food was flown in, the people refused it. “Food has always been given as a panacea, as control, in Haiti,” says Dupuy.

Josh Dewind, who has been studying the impact of these economic policies on immigration says, “they will do little to stop the flow of Haitians to the US. In fact, Haitians will continue to leave those conditions.

In her steamy kitchen, Therese is standing over a huge boiling pot of green plantains. The rice and djon djon (a mushroom sauce) are on a back burner, pigs’ knuckles are steaming alongside Saturday dinner for a houseful that usually includes a recent arrival whom Therese has helped come to New York. This afternoon, Therese is frowning. She’s worried about her plans to visit Haiti, because ‘”There’s so much confusion.” She’s also worried about reports of attacks on Vodou priests.

Many priests became Tonton Makout as part of papa Doc’s brilliant manipulation of Vodou. By turning these natural community leaders into police, Duvalier brought their communities under control. The trade-off for priests was protection. In the past, anti-superstition campaigns launched by the Catholic Church and the government had led to the murder of Vodouists. Since Jean-Claude Duvalier left some Makout priests have been killed and temples have been attacked again – this time because they are symbols of state abuse. But for Therese, these attacks also symbolize the recurring attack on the religion itself. Sure, some priests, delirious with power in Haiti’s macho culture, have done bad things, but so do corporate executives, politicians and western doctors. It doesn’t mean all business, politics or medicine is evil..

The “evil” accusations against Vodou are deeply troubling to Therese. She is a respected healer, with clients who come from Connecticut and New Jersey, and others who pay for her to go to Montreal or Jamaica so they can enlist her powers as a spiritual guide, herbalist, significant dreamer, and practical adviser. The African spirits (in their Haitian mutation) that she seeks to communicate with and through have very human personalities, are considered more accessible than God and offer worldly advice. There is no compartmentalization of secular and spiritual, no absolute dualism of good and evil. While Therese recognized that some priests exploit Vodou to augment their power, she also knows that it was a Vodou ceremony that launched the slave revolt in the early 1800s and that Vodou family networks buffered people during the hardships of the Duvalier era.

Today, Therese has another problem, one that will require both spiritual and secular treatment. She’s got to raise $2000 (the standard cost to pay off the right people to get a Haitian passport) to “bring out” yet another nephew who needs a complicated operation – and a job.

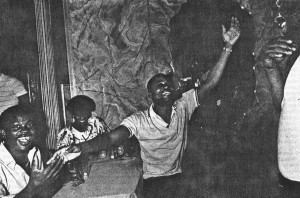

On Friday night at Club Cenegal on Flatbush Avenue, the restraint of the well-dressed couples drops when they hit the floor and lock into the slow grind. Coupe Cloue is singing tonight, his songs filled with double entendres way beyond the risqué: Coupe Cloue, the preacher-rapper whose songs mock the pretensions of Haitian men and women in their love-making and taking. In the middle of one of his hilarious and “tres naughty” love raps, he spins off about Haiti – “Liberty, equality, fraternity, solidarity,” and the grinding couples unlock to raise their hands in the air and cheer wildly. Then their hips lock again and the couples are back into an embrace taking the compa rhythm down to half-time. Most are moving around a pleasurable amount of flesh, a symbol of health, happiness, and success in the Haitian community; a symbol of the possibilities here; a symbol rarely seen in Haiti.

I can’t help thinking about the gaunt children and adults back in Haiti, the families dependent on the hard work of the people in this room. Yet the dances in Haiti, whether indoors or outdoors, are more vibrant, more fun, freer. And while our cheers for liberty come easy in this club, it’s the people back home who stood up and continue to stand up against guns. For the majority in Haiti, there was nothing left to lose. The majority in New York have a lot to lose by going back to devastated economy under a Duvalierist junta. Still, at Club Cenegal the postures, mannerisms, attitudes, the rum, the language and tempos that fill this room are all Haitian. One culture. Two worlds.

i like my country……….