By posting s short documentary that I made forty years ago on this archival website, I learned much more aboutl the healing power of the world’s most maligned religion. A version of this article can be seen on Medium.com.

- Hi, My Name is John… I’m also from Haiti. I seriously in need of some answers now. Thank you. Kind Regards

John’s message popped up a few days ago on the “Comments” page of my archival website where I have posted descriptions and clips of dozens of my TV and radio documentaries along with my published articles.

I created this website back in 2011 to “house” forty plus years of my work as a journalist and filmmaker. As the years kept stacking, I added new work. Although there are some TV programs and interviews as well as articles yet to be posted it now has 90 posts or pages, many including short video or audio clips — documentaries about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa; about human rights trials in Florida involving two Salvadoran Generals; about slavery and the American Revolution; or world religions and their responses to the environmental crisis, to name just a few. Most of my “films” (in fact all were shot on video) were made for PBS broadcast and many in collaboration with Bill Moyers.

Among the more than two dozen radio docs and features posted here, (made for a variety of public and commercial radio outlets) are The Immigrant Experience, Women Classic Blues Singers, Stories and Storytellers, Kids Talk About Divorce, and the efforts by domestics in New York City to organize. Articles I have posted range from the first Cowboy Poetry festival in Elko, Nevada (1984) to a critique of travel in the 21st Century (2018). In other words, the posts — the work — represents a smorgasbord of ideas, themes and issues.

As with most websites, I can study the metrics. I know how many hits, reads or views my site attracts daily and what part of the world those curiosity seekers come from. And anybody can comment on any of it, although I play God first to approve comments before posting.

Consistently, over the years, the one page that has elicited the most views — three times more than the next in line — is a TV feature story I produced for one of the first network magazine programs, The World, at NBC in 1979. The story is called Manbo–A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. As soon as I posted it on my site, the comments began arriving.

- — Hi, I am a Haitian descendant, I’ve been persecuted from many different ways ever since I came to N.Y. I can’t keep job and specially finding a woman to love me. I came to this website that speaks highly about mama Lola vodou.

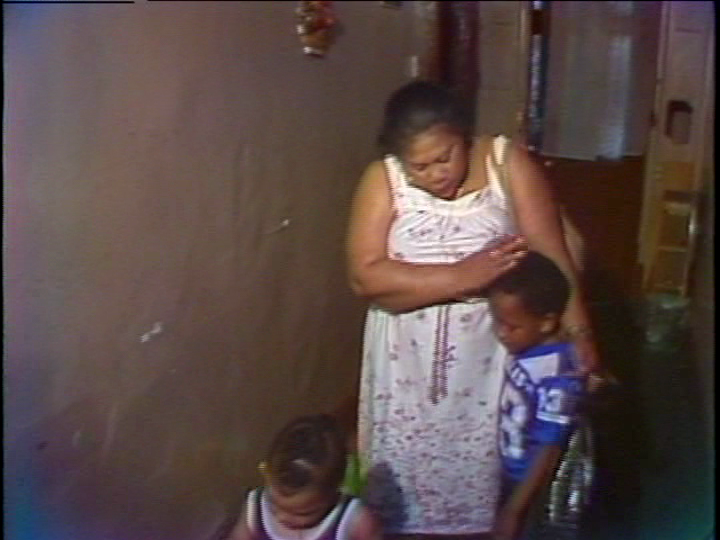

When I produced this TV story back in ’79 Mama Lola was unknown outside a small intimate family and community circle of Vodou devotees in New York. An emigrant who joined the mass exodus of Haitians during the Duvalier years (60s and 70s), she worked as a domestic while building a discreet and devoted clientele as a manbo — a Vodou priestess. She had created a hounfor (temple) and altar in her Brooklyn basement and would regularly receive clients for readings, healing procedures as well as ceremonies, assisted by her daughter, Maggie. Just as Mama Lola received her spiritual training from her mother, Maggie was becoming a Vodou initiate, a priestess in training.

Two of Mama Lola’s three sons were still at home and in school. Maggie and her two infant kids also lived in Lola’s house. A matrilineal household.

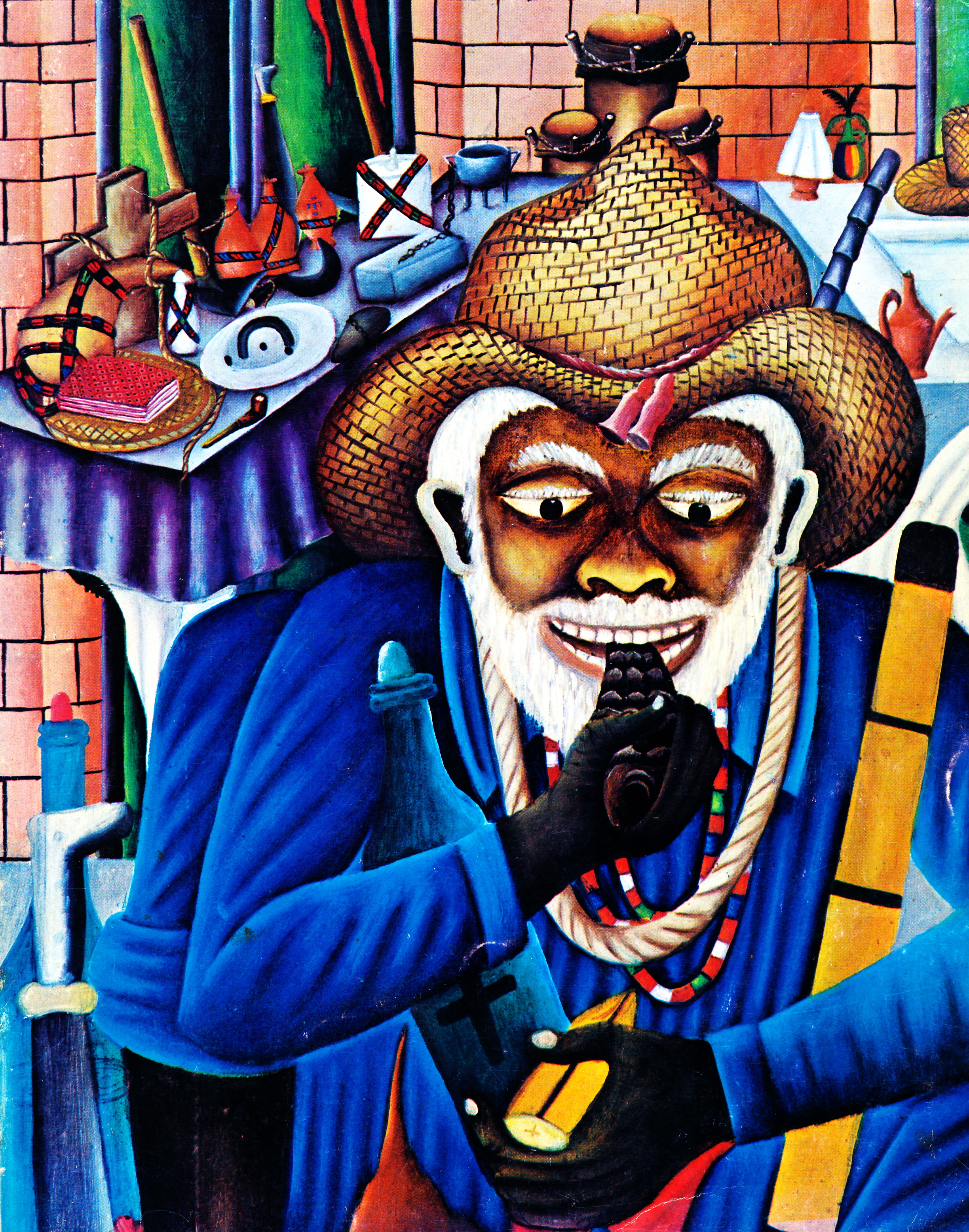

I met Mama Lola through Karen McCarthy Brown, an anthropologist and scholar of religion, in 1977 when the Brooklyn Museum sent me to Haiti with a video camera and microphone to produce a dozen short video docs about Haitian artists and their world including Vodou*. These short docs were part of the first major retrospective of Haitian art in the U.S.

*Vodou means spirit in the West African languages, Fon and Ewe.

The museum also hired Brown, who had written a book about Vodou ceremonial imagery, to study and collect images of Vodou altars in the New York Haitian community. One day, while editing material I had shot at a ceremony in Haiti, I invited Karen into my editing room. “Why is this man wearing a red dress?” A rich relationship ensued whereby we discovered the similarities between journalism and anthropology with all of its seductions and ethical challenges. How to hear and report the truth of another person. Another culture. Another universe.

“What the ethnographer studies,” Karen said, “is how people create meaning or significance in their lives. How they interpret objects and events.” I wished that journalists were more attuned to this sensibility.

(Several of the video docs about Haitian artists and a festival called Ra-Ra can be screened on my website)

- — I will like to know if can you please help me with an ex-boyfriend that I’m having problems with if you can please call me at any time at xxx-xxx-xxxx I would appreciate it that way I can explain more about what’s going on

- — I would like to get a reading, if possible other help as well. seriously in need, please help my kids.

About the time of the museum exhibition (1978) Karen had begun to develop a relationship with Mama Lola and I was eventually invited to attend ceremonies at her home. Coincidentally, I had been invited to pitch a few story ideas for NBC’s magazine program. After receiving permission from Mama Lola to film an interview with her and her daughter, to film card readings, a healing session and also a ceremony, Karen and I pitched a story outline to the deciders at NBC. They, predictably, were enthused about the exotic prospect of seeing a Vodou ceremony.

We saw it as an immigrant story including the usual low-paying jobs, but in the case of Haitian immigrants — more than 400,000 in New York at that time — it meant coping with racial and language prejudices while also being associated with the maligned and grossly misunderstood religion, Vodou.

The racism and the demonizing of Vodou meant that many Haitian immigrants denied that they practiced or believed in it. And all of this was before Haitians were blamed for the AIDS epidemic as it broke out in the early 80s.

This was a story of dual universes. In the opening scene we see Lola at her job cleaning a Manhattan apartment, then returning by subway to her world in Brooklyn. To a community where she is a respected spiritual healer. We see her altar room where she receives clients for card readings and consultations. They complain of job and immigration problems, heart-aches or difficulties with children. In another scene we see a practitioner receiving one of her sacred baths. Because of the fears of recrimination around Vodou, nobody would agree to having their faces revealed on TV.

- — I would like to get spiritual help as soon as possible for my family.

- — I was looking for somebody to help me with a situation and I live in New York and wanted to know if the problem could be taken care of. Do you have any recommendations of the best vodou priestess since you said Mana Lola is now retired and do you have a location, please, need help.

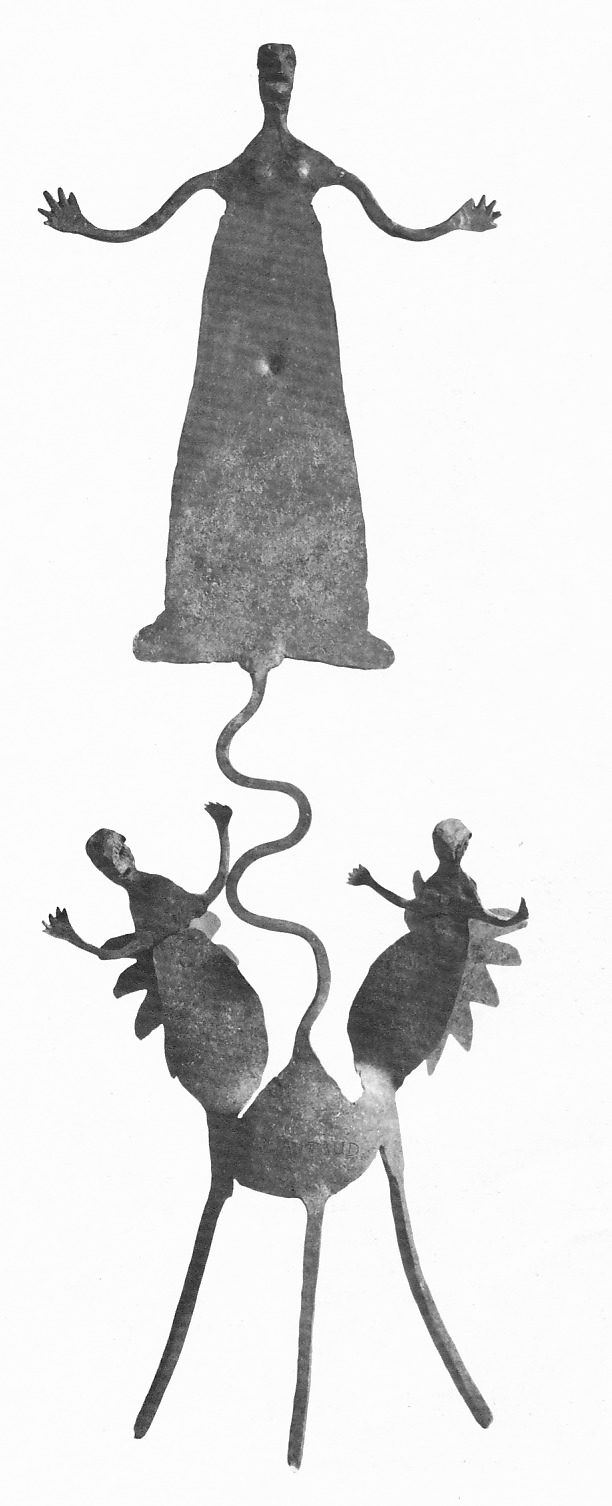

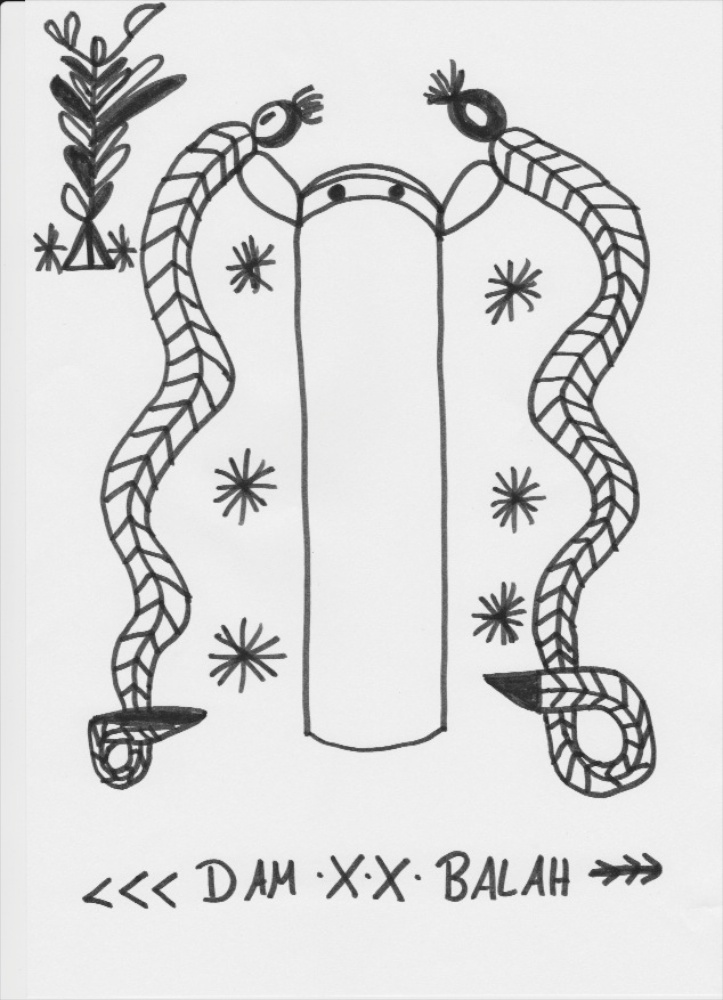

The interview with Lola and Maggie helps to unravel the mysteries of the religion, especially about the African spirits, the lwas, that came with the enslaved to the new world and merged with the Catholic saints of the slave owners, the masters, the colonialists — a phenomenon that scholars call syncretism. Images of the Virgin Mary and various Catholic Saints decorate Mama Lola’s temple and altar and are clearly understood as representing some of the vast Vodou pantheon of spirits — Llegba, Ogoun, Damballa, Papa Zaka, Erzuli, Ghede. For Mama Lola’s community — as for most Haitians — these are familiar characters — spirits who have human traits. During the ceremony the lwas or loas possess Mama Lola and talk through her with advice addressing the sufferings of the devotees who are seeking their counsel.

“When I came to New York as a young woman, I didn’t think I needed the spirits anymore,” Lola says. “But I was wrong. The spirits have helped me a lot here,” Lola describes the difficulties of earning a living, struggling with English, making her way in the city. “Yes, I needed those spirits to survive my life. The spirits protect me. That’s why I serve the spirits.”

The reason I am telling this story in text rather than directing you, dear reader, to a video clip or the full TV feature story is that in all of my archives this was the only video that disintegrated over the years. Some of the other videos shot in Haiti before this story have softened visually but are still highly viewable. The deterioration, well known to video producers, is traced to a particular quality of video tape that was sold in the late ’70s. Consequently, when posting this story on my site I was only able to capture a few still frames from the original video to add to a text description.

Yet, the responses keep flowing in.

- — I need some help with my marriage. Someone is trying hard to destroy my marriage. Can you help please

- — I really need to talk to a voodoo priestess asap anyone with information who would help me thanks

Even though I repeatedly answered the early responses that this was not a service website, that Mama Lola was retired (I posted this story on my site some 30 years after producing it), and that there was no way to contact her through my site, still the pleas for help kept arriving. And for some time now I have stopped approving them for posting on the site. But that hasn’t stopped the flow. The responses reveal a world of pain. Soul pain.

- — I need help can you please help me I’m lost.

- — I lost everything, and family. I want my wife to come back to me asap. I want my daughter and step daughter back. I want my house back. I want my job back with Lyft and Uber. Help me regain my life back now please. xxx-xxx-xxxx Call me

The responses reveal a world of pain. Soul pain.

In our TV story we witness Lola and Maggie preparing for a ceremony — what Lola calls a “party for the spirits.” The dining table is spread with cakes and cookies, grapes and watermelon, candles and objects that they believe the spirit enjoys. Streamers are strung across the ceiling. Lola anoints the space with her asson — her sacred beaded rattle. On her linoleum floor she draws a veve — a complex symbol for the spirit who is being celebrated and called upon here. A chicken will be sacrificed and cooked, then served to the participants.

Haitians know that this is a far cry from a hounfor or Vodou temple in Haiti with its dirt floor and sacred pole at the center around which veves are drawn and hours of hypnotic drumming directs and shapes the dancing and unfolding of events.

In Brooklyn Lola doesn’t want to attract critical attention from neighbors so she doesn’t hire drummers. When our cameras are rolling at Lola’s house, this ceremony begins, like all Vodou ceremonies do, with prayers calling for some of the spirits. Lola and Maggie are dressed in white, as the initiates and devotees in Haiti would be. And, as in Haiti, the dancing and chanting of prayers is punctuated periodically with “Ayibobo” (a kind of “Amen”). Mama Lola sprays rum from her mouth on the floor. As in all ceremonies in her house, Mama Lola will become possessed by one or more of the spirits being invoked that day.

On camera Lola and Maggie describe the lies that are told about Vodou, the religion that has sustained them. “So many lies,” repeats Maggie.

I would like to think that since we first produced that story forty years ago, that the attitudes in the media and on the ground about Vodou would have changed. That the voice of Edwidge Danticat, a remarkable Haitian-American storyteller, novelist and memoirist, would have educated readers about some of the complexities of Haitian culture, including its religion. Her stories bear witness to the violence that Haitians have suffered historically as well as after arriving on these shores. Yet it seems that almost every time major journalism outlets refer to Vodou it is in a derogatory or mocking manner.

During the 1980s and 90s when Haitians struggled to recover from two decades of Duvalier dictatorship, when their freely elected leader, Aristide, was deposed in a coup, not once, but twice, reporters often linked Vodou with the violence in Haiti. While everyone would acknowledge that Papa Doc had manipulated the religion for his own ends, President Aristide, the former Catholic priest, had brought back a new respect for Vodou so steeped in African beliefs.

Vodou has also been vilified because a Vodou ceremony was credited with inspiring slaves to revolt against their French masters igniting the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) — the first and only overthrow by slaves of their masters to create an independent republic. Instead of embracing the Haitian Revolution as part of a significant 18th C trilogy along with the American and French Revolutions, the new U.S. government along with other slave trading colonialist countries blockaded and essentially gagged the new black republic since news of that revolution would undermine their highly profitable slave trade and labor.

The Haitian Revolution was “silenced” by historians, other scholars and reporters according to Michel-Rolf Trouillot, a Haitian-American historian and anthropologist in his provocative book “Silencing the Past.” He compares this silencing of the Haitian Revolution with Holocaust deniers and the misinterpretations of the Alamo.

In their ahistorical writing reporters often don’t consider what happened during the two centuries following the Haitian Revolution. France literally made Haiti pay for their revolt by imposing a back-breaking debt — 21 billion dollars — recompense for their “property” loss that has crippled Haiti for two hundred years.

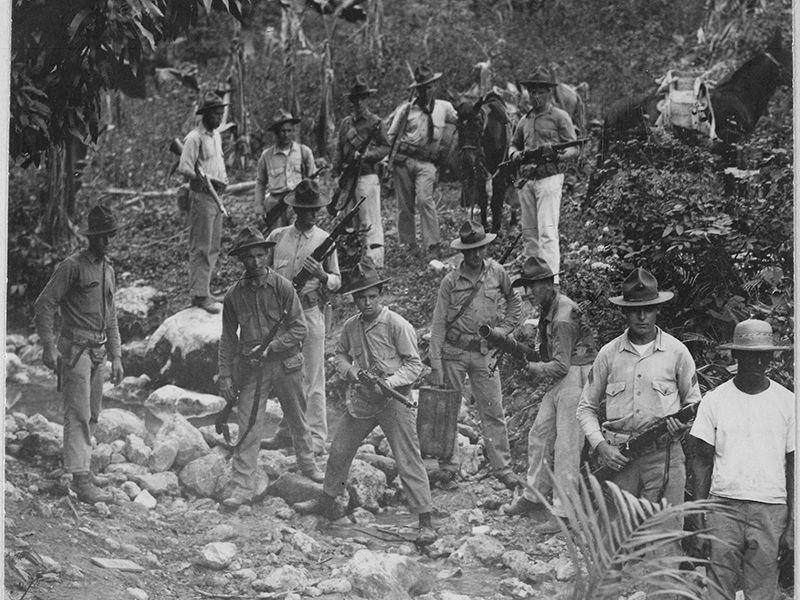

By the dawning of the 20th Century Haiti would discover a new interloper on their shores. A humiliating occupation by the U.S. marines that morphed into continual interference for the rest of their contemporary history. Of course, it doesn’t mean that Haitians had no agency in their own troubles with establishing a stable government or sustaining economy. But it is important to understand the price they paid for their revolution and the odds of a struggling nation to defend itself against the meddling of a powerful neighbor.

Within three days of the devastating earthquake in Haiti in January 2010, David Brooks blamed part of Haiti’s perpetual problems of poverty and resistance to development on Vodou, which, he claimed, “teaches that life is precarious and planning is futile.”

- — I would like to get spiritual help as soon as possible for my family

- — I need help with my marriage. Someone is trying to destroy my marriage. Can you help please.

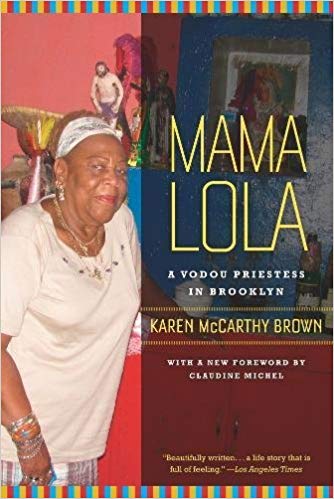

“It is no exaggeration to say that Haitians believe that living and suffering are inseparable,” says Karen Brown in a book she wrote about Mama Lola a decade after our TV story. “Healing is at the heart of the religions that African slaves bequeathed to their descendants…There is no Vodou ritual, small or large, individual or communal, which is not a healing rite,” she continues.

Everyone in Mama Lola’s family style Vodou practice seeks a therapeutic result when the spirits arrive by possessing her. The spirits then speak through Mama Lola to the supplicants, giving advice, counseling, soothing. There is always the potential for catharsis.

Given the range of problems Mama Lola addresses, from health and work, to family and love, Brown suggests, “She combines the skills of a medical doctor, a psychotherapist, a social worker and a priest.”

- — Hi. I would like to know if you do work for people like a voodoo work to help with a problem let say bring someone you love back like I want a man to be back in my life after everything I sacrificed for him And he decided to hurt me and leave. If yes don’t hesitate to contact me

- — I need to talk to a vodou priestess because me and my family need prayer and help. Anyone with information that would help us would be so appreciated.

Vodou functions like most religions with their rituals of community gathering to pray and sing. Haitians usually sacrifice an animal to be cooked and distributed to the congregants while Catholics eat and drink symbolic materials representing the body and blood of Jesus Christ. In most world religions all of this is a form of devotion, of faith, that is meant to address suffering of everyday life, and the terrible pain of losing loved ones. Most religions address the anxieties of death by offering idealized concepts of life in the hereafter. That hereafter is offered to those living by the moral code put forth by the religious texts. Adherents seek absolution for their sins in order to gain entry.

Vodou, like many indigenous religions in sub-Saharan Africa, has a more complex notion of good and evil embracing the idea that both reside in everyone and that the moral conversation is endless. A survival ethic often rules. And the daily presence of the spirits — honoring them, placating them, consulting them — is part of that process of moral behavior and healing. Vodou also differs in its approach to death. Adherents believe that those who pass to the afterlife join up with those not yet born, creating a continuity. The ancestors who have passed play a key role in the lives of Vodou devotees. There is a continuum of past, present and future.

Lola communes with her ancestors through dreams, she tells us on camera.

And what about God, many outsiders ask. Mama Lola will explain that the spirits — the lwas or loas — are the mediators between God (Bondye) and the living. Bondye does not get involved in the day to day life of human beings. “He’s too busy,” Lola tells Karen Brown. Haitian Vodou devotees are usually also practicing Catholics. And yes, the Catholic moral dictates can butt up against the tolerance and situational morality of Vodou.

Occasionally news stories have emerged where a fatal fire in an New York apartment or house was caused by vodou candles or a child killed through a purposeful act of evil that the perpetrator then blamed on Vodou. Mama Lola distances herself from these stories of abuse, but they have contributed to disparaging the religion and driving it further underground.

I have never seen a reporter compare the occasional news of vodou misused to the enormous sexual abuse scandal in the Catholic Church. Or the consequences of the political meddling of the fundamentalist controlled Christian evangelical churches of the U.S. Or the violent, terrorists who claim Islam as their religion. Or Buddhists committing genocide in Myanmar. Or in the U.S. the participation of many religious denominations, like the Baptists for example, in rationalizing slavery or opposing women’s or gay rights. Yet, included in the Vodou spiritual pantheon is Ghede, who protects children and gays. And women have always had access to the “priesthood” as Manbos.

Meanwhile, respondents to my post on Mama Lola continue to search for solutions to their painful predicaments:

- — I need help it’s 5 if us in my family that’s all I can tell you it’s getting bad… Too much evil asap contact me thanks

- — I am interested in Vodon. I was first initiated by my father and he passed before I could go to the next step, I have tracing Mama Lola for two years, I met one of her spiritual child. He told me he would introduce me to the daughter. I know Mama Lola has retire, I just do not want to put into the wrong hands. I take this very serious. Please assist me.

In a final sequence for our TV story, we shot Lola being possessed by various spirits. Cousin Zaka, the spirit of agriculture, Papa Ghede, and Ogoun, the most powerful of all.

Except…and it’s a big exception… Mama Lola is alone at this party for the spirits that we are shooting. Not exactly alone. Maggie and the kids are there. But nobody from Mama Lola’s community, none of her devotees, would agree to attend with cameras present. That’s how fear, humiliation and prejudice worked in 1979 New York. We used a variety of photographic images from other ceremonies that Karen had attended and shot with a still camera. But the story, devoid of an exotic ending — live animal sacrifices, wild drumming and delirious people — never satisfied the powers of NBC and never aired. Karen showed it in classrooms for years afterward until it deteriorated. But in its defunct state, posted on my site, it continues to attract damaged, hurting and needy souls.

- — J so beaucoup de problemes, je voulais savoir qu es ce qui m arrive. Merci.

- — I need help with a spell is it possible you or another priestess can assist me with it please let me know thank you.

Karen Brown became initiated as a vodou priestess a year after our TV story effort. In 1991 her book, Mama Lola, a Vodou priestess in Brooklyn, was published. It is a radical approach to anthropology as it weaves the story of her relationship with Mama Lola while decoding Mama Lola’s narrative in the effort to unravel the belief and practices of Vodou. Karen referred to it as an “ethnographic, spiritual biography.” However it is classified it was the first serious treatment of Vodou by academia, especially in the field of religious studies. Brown, who joined the ancestors much too early in 2015, believed Haiti had something to teach the world. To understand that statement I direct you to her book.

Largely through the success of the book, Lola was invited to speak at museums and universities from California to Benin. She was hired as a consultant to work on the UCLA Fowler Art Museum “Sacred Arts of Haiti” show in 1999 which traveled to the Museum of Natural History in New York. She consecrated the altars for both venues. Her own practice broadened as she was invited to the west coast, Montreal, Miami and New Orleans regularly to initiate new practitioners to the religion and often took initiates to Haiti for ceremonies there. Maggie continued to assist her mother while working as a health aide. Maggie’s daughter, Marcia, has chosen to be initiated as a Vodou priestess like her mother, grand-mother and great-grandmother, continuing a line of spiritual healers.

- — I’m of Haitian descent and also looking for Voodoo priestess in the NYC area.Thanks

Meanwhile, Dowoti Desir, a Haitian-American who was an art and anthropology student intern on the important exhibit of Haitian art at the Brooklyn Museum back in 1977, is now an initiated Vodou priestess with an academic and activist practice and lectures widely. She insists that “Vodou has been a source of empowerment for generations of Haitians.”

The point of all of this should be obvious. One would hope that by the 21st Century we would recognize human suffering everywhere, but most especially among immigrants, migrants and refugees, especially among people of color, among the poor, among the struggling classes, broken families, broken lives— and be able to not only honor our cultural differences but acknowledge our commonalities, our life predicaments, our suffering, our needs. Our soul pain. And that people may seek solutions and guidance — from organic and chemical substances to law and justice, from psychotherapy to dancing, music, and art. Many search for meaning and healing in spirituality and faith in any variety of religions including Vodou. Or in all of it.

- — I’m seeking some help if possible. Please.

- — I want to know if you do love spells. Thank you

This Was wonderful as always. Really great images and such a celebration of Mama Lola and Karin Brown. Thanks for sending this. Best.

Awesome article Much needed now as before . Proud Haitian Woman