out of fear of the Tonton Macoutes (Duvalier’s dreaded secret police). Haitians would not talk about the Macoutes or anyone of their problems, because complaints to the wrong person could end in arrest, beatings, torture, or even death.

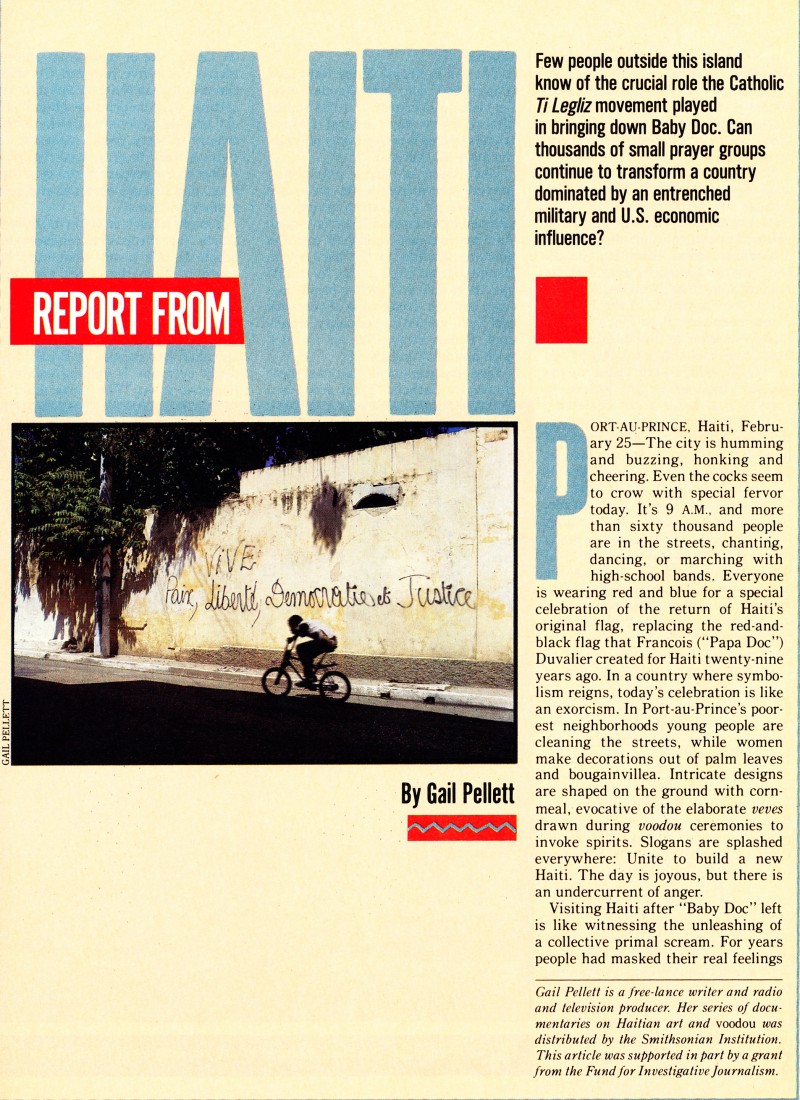

Now, across this small country — about the size of the state of Maryland — feelings are being released in every form imaginable. Political graffiti is smeared in red paint on adobe walls, demanding work, education, health care, justice. Teenagers wear-T-shirts reading Operation Dechouke (Haitian Creole for “uproot”). In the Port-au-Prince cemetery, Papa Doc’s mausoleum is smashed by furious protesters. Mansions — including a number owned by the Duvaliers — are burnt to the ground. Businesses are gutted — a supermarket here, a car dealership there. The six million inhabitants of the western Hemisphere’s poorest and hungriest nation are angrily bidding good riddance to their detested dictator.

But amid the anger and destruction , there are also signs of gratitude. Throughout the countryside, crosses and altars are lovingly erected. In many towns the yellow-and-white colors of the Catholic church fly alongside the nation’s new red-and-blue flag. And in Port-au-Prince, market women are selling plastic bags inscribed Merci legliz. On this day of celebration of the end of the Duvalier regime, the people of Haiti know that this change in power is due, at least in part, to the work of the church—and its offshoot Christian base communities, groups centered in native “little churches” (in creole, Ti Legliz).

But amid the anger and destruction , there are also signs of gratitude. Throughout the countryside, crosses and altars are lovingly erected. In many towns the yellow-and-white colors of the Catholic church fly alongside the nation’s new red-and-blue flag. And in Port-au-Prince, market women are selling plastic bags inscribed Merci legliz. On this day of celebration of the end of the Duvalier regime, the people of Haiti know that this change in power is due, at least in part, to the work of the church—and its offshoot Christian base communities, groups centered in native “little churches” (in creole, Ti Legliz).

It is already dark when we leave the main road that links the densely packed communities clinging to the possibilities of prosperity I Port-au-Prince. I inch the car up the narrow roller-coaster alley because, like everywhere in Haiti after dark, the road serves as a living room. It’s Saturday night, and a thick wall of people separate in front of my headlights. I park the car where the road ends, and then my Haitian companion and I walk the rest of the way along narrow paths that snake through a congested neighborhood of concrete block-and-plaster houses. There’s no light, so I try to sense the location of the wastewater streams that trickle everywhere in this city.

The air is heavy. Since Baby Doc (Papa Doc’s son, Jean-Claude Duvalier) left on February 7, it has rained almost every day. Several Haitian friends tell me it is God’s way of washing away all that evil.

The sound of voices murmuring prayers comes from a tiny two-room house as we approach. Sixteen people are jammed into a circle in the front room. Another four are squashed into the doorway leading to the back room. Ranging from their teens to middle age, these men and women begin singing a spirited Creole song about work and food, justice and equality. Hands clap. Bodies sway The air is thick with humidity and sweat.

The sound of voices murmuring prayers comes from a tiny two-room house as we approach. Sixteen people are jammed into a circle in the front room. Another four are squashed into the doorway leading to the back room. Ranging from their teens to middle age, these men and women begin singing a spirited Creole song about work and food, justice and equality. Hands clap. Bodies sway The air is thick with humidity and sweat.

Like 80 percent of all Haitians, these people are Catholics. Their group is a Ti Legliz, one of more than an estimated thirty-five hundred Christian communities in Haiti. In this informal setting with no priest or church official present, groups of anywhere from twenty to forty people meet once or twice a week to pray, read the Bible, reflect on the gospel’s meaning in their lives, and discuss personal and community problems.

Tonight a truck driver in his thirties starts the discussion, encouraging people to talk about what has happened to them that week and their feelings.

A woman angrily complains that Albert Pierre, familiar to all in the room as the hated Chief of Police under Duvalier, has escaped to Brazil. Suddenly everyone is talking excitedly. Someone says, “The junta must do everything to get him back.”

“I don’t think they are serious about getting any of them back,” responds another.

“I don’t think they know how to get him back,” says a man in his 20s.

Soon all are discussing post-Duvalier justice. What is the right way to deal with former Tonton Macoutes? Across the country, people are killing them. Many Macoutes have gone into hiding “This can’t go on – this killing, the wrecking of houses, and this burning . We need a justice system,” a voice injects.

No resolution is reached, but all who wish to speak are heard. Between rounds of talk, there are more songs. And then the conversation turns to workaday lives. A wiry woman , the mother of two girls playing in the back room, talks about her difficulty supporting her family on $30 a month in a country where a chicken costs $3. A gaunt man describes how his child swallowed glass and had to be treated at a hospital. A nervous young man talks about his unsuccessful search for work (unemployment in Haiti is estimated at 50 percent; it may be much higher). Another man brings up a demonstration he took part in at the Customs House, where the people are trying to remove corrupt administrators.

The humidity is unbearable. Someone puts a fan on a table in the center of the group. It adds precious little coolness, but the meeting continues. A man of about twenty-five reads a selection from the Bible. And the rain begins. The reading is from Matthew – the story of Jesus in the wilderness being tempted by the devil. An office worker, Alexandre, begins to comment on the selection, pointing out its significance to current events in Haiti. “We’re being tempted, too,” Alexandre says, “tempted to take justice in our own hands. : a But people are restless; the sounds of rain crashing down on the tin roof makes it difficult to hear. Finally someone passes around several bowls of marinade, a spicy deep-fried bread. There are final prayers and a song, and then the twenty people scatter back to their homes.

The Ti Legliz are a Haitian variation of the Christian communities that have spread throughout Latin America in the last twenty years. These little churchs are the structural form of the liberation theology that has been articulated by priests and bishops like Father Gustavo Gutierrez of Peru and the late Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador. Haiti’s Catholic bishops, priests and lay workers explain that liberation theology begins with people, not God. “It is not spirituality in the sky,” one seminarian says,” but addresses the concrete conditions of life on earth. It sees Jesus as a brother, as spiritual support for changing the condition of poverty and injustice”

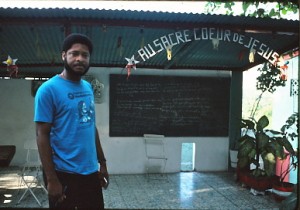

The name Ti Legliz was coined by Father Pollux Byas, a fifty-year-old priest in Pilate, a town of forty thousand, spread out on coffee growing hills in Haiti’s northwest, far from the racket of Port-au-Prince. Pilate – an hour’s drive off the highway along a terrible road that is washed over by five small rivers – is where the base communities started in Haiti more than ten years ago.

Now, Byas explains, there are more than three hundred in his parish. “They meet twice a week — once for prayer, gospel and sharing “During the second weekly meeting, he says, they deal with needs – health care, food, housing. “It’s a movement of community, of solving problems collectively.”

The Ti Legliz stress literacy, education, and organizing to solve problems. Equally important for the immediate future are the movement’s efforts to provide necessary goods and services. For example several Ti Leliz in Cap Haitien, Haiti’s second largest city, have started nonprofit stores that provide food, building materials, and medicine at lower prices. Other groups are developing agricultural cooperatives and schools to train the unemployed.

“The most important part of the Ti Legliz movement is that it encourages people to think, to ask questions, to calculate and analyze their problems, says Father Albert Gouin, a forty-eight-year-old priest. The Ti Legliz, according to Gouin, emphasize participation and community. Encouraging people to move beyond resignation and fatalism. The Ti Legliz movement uses trained animateurs, (like the truck driver in the meeting I attended), lay workers who are of the same social class as the group, to stimulate discussion, read the Bible (others may not be able to read), and “animate” reflection and analysis. In describing the process, Gouin uses a word I hear from priests and lay workers throughout Haiti consciencization. This new word in the Creole vocabulary means “consciousness raising.”

The movement receives support and guidance from Catholic church workers. “We are the resource people,” says one nun, a school principal who also works with youth groups. In Gonaives , the Bishop’s Mansion provides work space for a group designing literacy and agricultural projects and an education program for peasants. Haitians are quick o point out, however, that the Ti Legliz is not run by the church, but by lay people.

Haitian church officials are just as quick to point out that the Ti Legliz movement and Haitian liberation theology are not something that they have studiously copied from their Latin American neighbors. “We don’t learn liberation theology from books,” Bishop Francois Gayot, head of the Haitian Conference of Bishops, tells me when we talk in his hometown of Cap Haitien. “We looked at Tonton Macoutes, at the abuse of government functionaries, their corruption. We asked, “What does God think about this? What are the causes? What are the distortions between the word of God and reality?

“When you see the cause you can find the remedy,” Gayot concludes. “This is how we learn liberation theology, not in books from Latin America.”

While the Catholic church is now a force for change in Haiti, it was not always so. For more than a century the church aligned itself with the ruling elite. But two events of the ‘60s laid the groundwork for a socially conscious church in Haiti. The first came, oddly, through Papa Doc Duvalier, who “nationalized” the church, replacing foreign-born priests and bishops with Haitian natives.

Secondly, Vatican II led to the church’s identification with the poor and the oppressed. In Haiti where church officials previously worked to educate and serve the upper classes, energy and resources now were turned to the poor majority. This meant liturgical changes as well – masses sung in Creole, not the elite’s French; voodou drums now accompanying new hymns that call for equality and justice. In 1980 the church began speaking out about abuses by the Haitian government.

When Gayot was elected president of the Conference of Bishops in 1982, “he made an enormous difference in Haiti, because he was committed to the fight for hman rights,” says Father William Smarth, a priest exiled by Duvalier in 1969. Under Gayot’s leadership the church began pressing harder for reforms and issued statements complaining about human rights abuses and widespread poverty.

When Pope John Paul II came to Haiti in 1983, he electrified many church workers by stating, “everything here must change.” Then in January 1985 Gayot and the Conference of Bishops composed a letter to youth, which was read from many Haitian pulpits. It challenged Haiti’s young people to action during the United Nations-sponsored International Youth year. “I have seen the affliction of my people and heard their cry. I have come to deliver them,” the letter quoted from Exodus. It went on to appeal for involvement: “Stand up: 1985 is your year! What do you want to make of it?” The church then organized a March for Youth. On February 2, 1985 tens of thousands of young people walked from church to church all over the country. Sixty thousand marched in Port-au-Prince alone, where they carried banners reading. We march for peace, participation, justice, democracy. In April 1985 the church released a paper critical of the Duvalier government’s policies and practices.

Through its Creole-language radio station, Radio Soleil, the church also offered a voice for charges against the government. As a result, radio Soleil was frequently shut down by Duvalier’s police. Three months before Duvalier left, Haiti’s youngest bishop, Willy Romulus, encouraged citizens to write or telephone their complaints and protests to the station. Soon after the campaign began, Romulus’ life was threatened. When the locals heard this, thousands poured into the streets surrounding his residence to protect him – including peasants from the nearby countryside. The peasant “security guards’ slept overnight in the streets to ensure Romulus’ protection. The audacious free-speech campaign of Radio Soleil is credited by almost everyone with puncturing Duvalier’s last illusions of legitimacy.

A DAY IN LATE February 1986, 8:30 AM. – Already more than thirty people are lined up outside the old school building on Rue aMarre in downtown Port-au-Prince. Inside this building are the offices of Radio Soleil. These people are here to voice complaints and make suggestions. It has been weeks since Duvalier’s fall. The Tonton Macoutes have been disarmed, killed, or forced into hiding. In the absence of a working judicial or parliamentary system, Radio Soleil is functioning as the town meeting for the country.

A huge, overweight man in his fifties comes to the microphone to defend himself. His neighbors claim he was a Tonton Macoute; he says he was not. Here at Radio Soleil, he says, all he wants is a chance to speak for himself. He is given the chance.

A group of teenage boys fall into the station out of breath, having run all the way from their town on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince. They have been accused of attacking the temple of a local voodou priest, and they claim the priest has hired someone to burn down their home. They want to explain their situation on the radio, hoping their statements will be believed.

A phone call comes in from Port-au-Paix in the far north. An old peasant woman – perhaps she is calling from a local church telephone since few Haitians have their own phones – is complaining about the kind of aid that comes to Haiti from other nations “We need tools not clothing and food” she yells through the crackling telephone line.

The line of people outside the station grows longer. Meanwhile, a member of the radio station’s staff displays the letters that have been received recently. There are stacks and stacks, each letter representing a problem – hunger, high food prices, lack of work or services, problems with wages or working hours, abuse by local authorities, a dispute over land or money. Somehow, it is hoped Radio Soleil will help resolve these dilemmas. Since 80 percent of Haitians are illiterate, many of these letters have been dictated to priests or to the few other Haitians schooled in reading and writing.

Teaching the Haitian people to read and write is a major concern of the church today. The bishops have launched an extensive drive that aims to make three million people literate in five years. “New winds are blowing here,” Gayot told a rally of tens of thousands in Port-au_Prince in March. “In five year there will be no more illiteracy.”

The literacy drive will use Creole, the language of the people. The campaign’s name in Creole is Goute Sel, which means “taste of salt.” Popular mythology in Haiti says that the food of zombies – people stupefied by voodou priests – must be prepared without salt. The implication is that illiterate people are also zombies and the “salt” of reading will offer the Haitian people the potential for a better life. The literacy program will also use the methods of Brazil’s educational philosopher, Paulo Freire. “It’s not just a program to read and write,” explains Father Jean Hanssens, a Dutch priest who trains Ti Legliz animateurs in central Haiti. “It’s a consciousness-raising method of education. It makes people aware of their dignity, their rights as citizens.” The method, Hanssens explains, is based on teaching key words like community, democracy, and market.

It is 8 p.m. on a Wednesday. Eight hundred people, mostly women from their twenties to their fifties, are gathered in Saint Gerard’s Church, up a steep hill on Port-au-Prince’s back edge. We have been listening for two hours to a passionate sermon about the right to work and equality. As each point is made, a chorus of women’s voices punctuate it with a key word – “truth” or “justice.” The sermon is also broken up by songs. Outside the church teenagers use the few electric lights on the grounds and street to do their homework and read books.

Saint Gerard’s has a reputation for excellent work with young people, thanks to its priest, father Gabriel Beinaime, who has been working here since 1978. On weekends some fifteen hundred teenagers participate in either adult literacy (three hundred are teaching classes) or reforestation (they are planting in the watershed area behind Port-au-Prince). Bienaime says. As he shows me an outdoor classroom built into the hillside, he explains that the most important part of the youth activities is consciousness raising. “They are learning to analyze problems.”

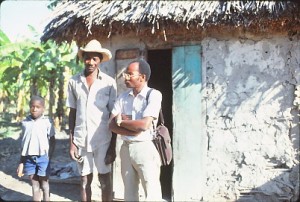

The city of Gonaives sits at the edge of a desert in northern Haiti. There are no trees for shade, only dust and heat and ras le bol – people fed up with the situation. Here I meet thirty-one-year old Luciano Pharaon who left the seminary to devote his time to teaching and organizing as a lay worker. Pharaon introduces me to some peasants in the nearby countryside who breed pigs. Jacque Antoine is wearing the work clothes of most peasants – a loose cotton shirt over cutoff pants that reveal his sinewy legs. He wears a straw hat against the merciless sun. As Antoine takes us over to a pen to see his prized pig, Pharaon tells me. “The pig is like a bank for the peasant.” But in 1978 swine fever broke out among Haitian pigs. The Duvalier government undertook a pig eradication program and slaughtered thousands of Haitian pigs. The peasants were suspicious from the start, unconvinced that all pigs should be killed. They grew increasingly disenchanted when, after a long wait, the government started offering a new breed of pig, a U.S. variety unsuitable for conditions in Haiti. The pig problem was a major factor in the protest demonstrations that began here two years ago. Today Pharaon and his friends are helping a number of peasants in the area with a new variety of pig that is sturdier and will bring more money on the market.

As Antoine and Pharaon chat, another peasant joins the conversation. His kay (the typical peasant’s small mud house with thatched roof) stands a few yards from Antoine’s. Other kays dot the countryside nearby – a reminder of the density of population, seven hundred people to every square kilometer of arable land, experts have estimated. And only 40 percent of the land is arable, and much of that is on mountain slopes. Seventy-five percent of Haiti’s population are peasant farmers, and survival is a desperate battle for two thirds of them.

Survival is also a daily battle for unskilled workers. Pharaon is working on that problem, too. Two years ago he and a few friends founded a vocational school with money provided by Haitian migrants to Montreal. Pharaon takes me to his school, where thirty young men are busy hammering and sanding amid bench presses, drills and stacks of old lumber. The students learn carpentry and build furniture to sell. “The school is free,” Pharaon tells me. “The students can sell what they make to pay for the cost of materials and earn a little. We’re self-supporting.”

Pharaon says these last words with pride. Here, as in the literacy campaign, there is more than specific skills being taught. “There is also an intellectual component.” He says. “We discuss social and political problems. The goal is learning how to shape a better future.”

Pharaon’s school, the first of its kind in Gonaives, speaks to the neglect of the provinces under Duvalier. Only the church provided educational and health services. Government services and wealth became concentrated in Port-au-Prince, sparking protests in the provinces. And it is in the provinces now that the most provocative graffiti and slogans appear. In Gonaives a banner reads, Liberty or Death. Another in Cap Haitien says “Welcome to the Bronx. We want decentralization “– referring to the U.S neighborhood most symbolic of neglect.

The government did not let the church’s activities go unpunished. When Chi-Rho, a Catholic youth organization, sponsored a woman’s consciousness-raising event on Mother’s Day last year in Gonaives, the police disrupted it. In early 1986 Tonton Macoutes surrounded the house of the Scheut missionaries and took their money. Other priests and lay workers have been beaten and imprisoned. In late 1982 Gerard Duclerville, a lay worker, was arrested during his training session with Ti Legliz animateurs. He was known for his early-morning radio talks about Latin American liberation theology. In jail he was badly beaten. The church protested and he was released just before the Pope’s visit in March 1983.

In the context of growing civilian protest (riots in Gonaives and Cap Haitien and the revolt of peasants in the Artibonnite valley against a hydroelectric dam that would force them off their land), the government stepped up its attack on the church. Priests were threatened, Tonton Macoutes entered churches with guns, grabbed microphone away from priests and intimidated congregations and members of Ti Legliz.

In April, 1984 a seventy-eight-year-old priest, Albert Desmet, was beaten to death by police, and in November, 1984 the government arrested more than two hundred Catholic lay workers who were working on adult education and literacy. Their thirty days in jail, where a number were beaten was considered a warning.

Father Pollux Byas in Pilate laughs when I ask him if he was ever frightened about government reaction to his work. “We priests have a saying that we walk with our coffins under our arms.”

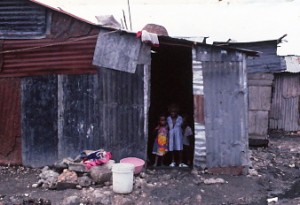

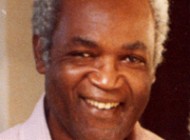

Attacks against Catholic activists further deepened their resolve. Gerard Duclerville who was badly beaten by the police and was left permanently deaf in one ear, returned to the Ti Legliz movement after his release from jail. Today, the gray-haired Duclerville works with some 250 animateurs in Port-au-Prince. He also teaches occupational skills at a simple facility in City Simone (renamed City Soleil after Duvalier left), a squalid shantytown of 250,000 people on the outskirts of Port-au-Prince.. “Families go for days without food here,” says Duclerville, as we watch a nude child with a distended belly eat from a muddy garbage heap.

THE DUVALIERS did not invent all of Haiti’s problems, but Jean-Claude’s departure has left an economy in shambles. His policies contributed to the conditions that has left more than 70 percent of school-age children with some form of nutritional deficiency.

Driving into the countryside, I watch townsfolk and peasants bathing in the irrigation and wastewater ditches. And each morning after my shower at the guesthouse, I walk onto the veranda and watch a child cup a leaf under a trickle of wastewater across the street. He uses the leaf as a funnel to fill a plastic bottle. Unsanitary water is the leading cause of disease in Haiti.

Even though the church has launched an educational movement preparing Haitians to determine their own future and has sharpened its analysis of structural poverty, its leaders are also reluctant to dictate an economic plan. “We are not technicians,” says Bishop Gayot. “Our role is not to present an economic or political plan, about to emphasize some fundamental values to underline all plans for Haiti.”

Gayot explains that church leaders hope that the interim government postpones elections for a year or so to allow political parties and candidates enough time to prepare. Haiti has had little experience with democracy or democratic institutions. In this interim period, however, Gayot is concerned with the potential for manipulation from both the Left and the Right. “I’m sure Haiti is looking for an original way to democracy,” he says, “not capitalistic, not Marxist.”

The church is supporting a number of worker demands, including trade unions, higher wages, and improved services. Pursuing these goals, it finds itself in conflict with a competing vision for Haiti – the US economic plan.

BACK IN 1981 the U.S. government and the World Bank devised a new industrial strategy for Haiti as part of the Caribbean Basin Initiative. It emphasizes assembly production for export to the U.S. market.

“Haiti’s largest natural resource is cheap labor” says Claude Levy, president of the Haitian Association of Industries, an organization that receives funds from the United States. “In the international market, the United States is losing to Asia, largely because of unionized labor. The answer for U.S. companies is to come to places like Haiti, where there are lower operating costs.”

“The whole country is a free zone,” Levy says. “For example, thirty U.S. companies use one complex. We provide the buildings, the contacts in government, the telex, the workers. They bring in the equipment and technical supervision.”

More than three hundred assembly plants in Haiti now produce garments and baseballs and assemble audio-cassettes and other electronic components. The minimum wage at the plants, which border the road to Port-au-Prince’s airport, is $3 a day. Although Levy claims some piece workers can make as much as $15 a day, the recent movement for a $1-an-hour minimum wage implies this must be rare, if at all possible. Levy is opposed to the $1-an-hour wage. “We can’t let wages go up, or we will no longer be competitive with the rest of the Caribbean. We can’t have unions in Haiti. It would be disastrous for business.”

A picture emerges of a giant sweatshop circling Port-au-Prince and serving the U.S. Market. No unions or benefits, if one is to interpret correctly a June 1985 World Bank memorandum. After detailing the disastrous state of Haiti’s economy, the report says Haiti will have to be export oriented. “Consumption, especially that of the public sector, will have to be markedly restrained in order to limit the growth of consumer goods, imports and to shift most of GNP growth into exports.”

Josh DeWind, director of the Immigration Research Program at Columbia University, is highly critical of this new strategy “The proposal to spur development through exports has led to an increase in the pressure for migration. To compete, salaries are kept low, and Haitians leave as a result,” he says. Furthermore, DeWind claims this strategy has failed in Puerto Rico. “The World Bank only looks at GNP, not at the distribution of wealth.”

IF THE ECONOMIC future is cloudy for Haiti, the political one is even more so. “The country needs a way to make a transition from a military to a civilian government,” says Karen McCarthy Brown, a sociologist at Drew University in Madison, New Jersey who has worked in Haiti and with Haitian immigrants in this country for fourteen years. “The key question is — will the United States, which has been calling the shots in Haiti for some time, react? Will it aid repression by sending a large amount of aid to the military, or will it let the Haitians find their way to their own form of government, even if it is unstable for a period of time?”

This thought has occurred to many others, particularly the Haitian clergy. “That’s why the U.S. flag was used in many demonstrations,” explained one priest, “to show the United States we were not communists, so it should not react negatively and interfere.”

Meanwhile, the church has unleashed a movement that will keep pushing for economic solutions and political change. In Port-au-Prince’s finest vocational school, students have organized themselves, kicked out the old director and instituted a government committee of two students, two professors, and two administrators. They have elected a new director based on specific qualifications that include technical expertise, connections with the industrial sector and a humanitarian interest in students’ lives. “They understand that the school is a microcosm of society” one instructor says. It’s a democratic model for citizen participation, but if the economy in Haiti doesn’t improve, the benefit may be limited “We probably aren’t going to find jobs here,” one student tells me as I leave the school,e “or if we do, the pay is nothing.”

Will the church’s program of education, consciousness raising and collective problem solving be given the opportunity for far-reaching change with the detachment and support of the Untied States? Or will the traditional resolution – an elite backed by a military strongman, in turn backed by U.S. aid and military hardware – end up determining the future of the country?

It is too early to guess the outcome, too early to imagine what will become of Haiti after Goute Sel and conscientization. And it is still far too early to determine which vision of Haiti’s future will prevail.

Thank you for publishing this article on line.

The murder of my uncle, Albert Desmet, described in the article, was very sad news fo me as a teenager in the 1980’s but until reading this article I had never really understood the political background to his death.

It had always been my understanding that his death had been as the result of an intruder or thief; the knowledge that it was at the hands of the police is comforting as I can only assume that he was seen as a problem and perhaps therefore, in some way, his death contributed to fall of the regime.

Laurence Desmet, Liverpool, UK

Beautiful article and beautiful story. Cesar

Dear Gail,

It was almost an omen to read your article on Haiti. In 1986 I went there for the first time and met with a good friend, once a priest, activist and prisoner of Duvalier the 1960’s. Jean Claude Bajeux was again a target of persecution in the days I was there and stayed with me at The Montana. It was from him I learned of the role so many priests had played in bringing down Duvalier as he reflected on the reality of Haiti. Your article brought back those conversations and yesterday my friend Marcia was visiting us and informed me that Jean Claude had recently died.

Thank you for the gift of bringing back those memories of Jean Claude Bajeux and the time spent with him in Haiti. He and his wife Silvie have a very special place each time I think of Haiti and its people.

Abrazo,

Diego

Sent from my ipad

Hey Gail Pellett. Your Article on Liberation Theology in Haiti was very informative for me! Before I continue my purpose for this message, please allow me to briefly introduce myself. My name is Kevin A. Hicks, currently pursuing to be a well-known artist, and I go by the stage name Leveille. My mother was born in Haiti; My father is African-American. Unfortunately, I grew up not knowing my dad. Fortunately, I grew up on my mom side of the family and learned the beautiful ways of my Haitian people. However, my Uncle who passed years ago and who was also a preacher, always called me “Ti Legliz” and I assumed because as a child I would reenact his ceremonies. I do speak creole, but my spelling and reading of this language is off. So today, thinking of my Uncle, I decided to look up the proper way to spell “little church” and discovered your amazing Article. Now I feel him calling me “Ti Legliz” means something much more. I will continue to look into more of your works and studies. I am also a basic entry level author, looking to meet other producers and authors of your caliber. Thanks for your time, and stay blessed!

[…] Haitian Liberation Theology differed from Latin American Liberation Theology due to its bottom-up or peasant-led movement. Priests and bishops were not the founding members of the Ti Legliz Movement in Haiti, but they did join the effort later on. Haitian Liberation Theology believed their theology began with individuals and not God in the sky, and that faith had to deal with life on earth. Jesus was described as one’s brother and as “spiritual support for changing the condition of poverty and injustice.” […]