“If you can’t do it on a horse, it ain’t worth doin’,” Melvin Whipple sighs pushing back his smoke-colored hat. Whipple should know. He has spent most of his 65 years working cattle — on horseback. It’s 2 a.m. and we’re on a train somewhere between Salt Lake City, Utah and Elko, Nevada. For two hours Whipple has been talking horses and cattle to another cowpoke, Everett Brisendine. At 79, Brisendine still enters the occasional rodeo when he’s not working on his ranch in Chino Valley, Arizona.

“If you can’t do it on a horse, it ain’t worth doin’,” Melvin Whipple sighs pushing back his smoke-colored hat. Whipple should know. He has spent most of his 65 years working cattle — on horseback. It’s 2 a.m. and we’re on a train somewhere between Salt Lake City, Utah and Elko, Nevada. For two hours Whipple has been talking horses and cattle to another cowpoke, Everett Brisendine. At 79, Brisendine still enters the occasional rodeo when he’s not working on his ranch in Chino Valley, Arizona.

Whipple’s small frame looks like a piece of beef jerky, his face like a topographical map of the Arizona rangeland where he worked cattle for several decades. Like Brisendine, he walks as if he’s got a horse between his legs. And like Brisendine, he has written a lot of poems about life in the saddle. Their dialogue is spiced with poetic lines. Before I go to fetch some beers, Brisendine recites his tribute to old cowboys, which ends. “They never really die, you know, they just smell that way.”

In the lounge car a group of young wranglers form Montana, North Dakota and Colorado are sharing tricks of the trade. “I give ’em a lot o’ leg,” snorts Nyle Henderson, an energetic 31-year-old horse-breaker with a handlebar mustache and a wide-brimmed black hat. It can take a good three years to break a horse and train it to work cattle, so the others listen intently as he describes his use of a snaffle bit. It’s insider talk. Yet despite his baffling terminology, I am riveted to Henderson. He has the gift of the storyteller, weaving “true” story into “tall tale,” and then reciting a rhyme based on that story, about an old mule name Ruth.

For the next three days, these men — and women — wearing big hats from the American Wst will recite what folklorists call “insider poetry” — stories in metered rhyme about their lives and their heritage.

It’s fitting that the first cowboy poetry gathering should take place in Elko, a traditional cattleman’s town. Close by there are still vast expanses of open range where cowboying is practiced much as it always has been, where it a still take four days to move a herd of cattle 50 miles at roundup. It is near here that buckaroos like 34-year-old Waddie Mitchell live and work and continue a tradition that most of us from the urban world never knew about: composing and reciting cowboy verse. One poem he likes to recite begins like this:

Though you’re not exactly blue

Yet you don’t feel like you do

In the winter, or on the long hot summer days;

For your feelin’s and the weather

Seem to sort of go together,

And you’re quiet in the dreamy autumn haze.

When the last big steer is goaded

Up the chute, and safely loaded

And the summer crew has ceased to hit the ball;

And, a feller starts a draggin’

To the home ranch with the wagon —

When they’ve finished shippin’

Bruce Kiskadon wrote these lines back in the 1920s. He’s been dead for more than 30 years, but his poetry is still memorized by cowpunchers throughout the West. Kiskaddon is only one of the late-lamented poet laureates of cowboy life. Badger Clark and Curley Fletcher have also bitten the dust. Their rhyming pentameters were passed around the campfire at the end of a long dirty day or printed in pocket-size books and stockmen’s journals.

Cowboy poetry can be traced back to the earliest days of cattle herding more than a hundred years ago. The act of making rhyming verse seems to have emerged from the solitary nature of the work, the long hours spent alone on a horse. It was an continues to be a way to amuse other wranglers at the end of the day or to liven things up while washing down the dust in bars.

Poetry and rhymes may no longer be the fashion, but the 100 or so cowboy poet who traced to Elko are sticking to their guns. “I hate that (modern) poetry with a passion,” says Henderson, who traces these feelings back to his school days. “My teacher would hand you a poem on a sheet of paper. The first lines stretched from here to the end of the room. None of it rhymed or made any sense and after I got done stumblin’ my way through it, the teacher would look at me and ask the question. “What’s the poet tryin’ to tell ya?” Nyle pauses for comedic effect. “And I’d say, “I figured he wasn’t tryin’ to tell me nothin’ or, if he was, he done a poor job ’cause’ there weren’t none of it sunk in.” And the school teacher would say “Wrong again.” I graduated from high school thinkin’ my name was ‘Wrong Again.’ Anyway I made this here poem called ‘I Hate Poetry.’

I hate poetry. I can’t really say why

And yet I write some. At least I try.

I write about things that I like best

Old horses, and cowpokes and places out West.

But most of my poems are special, you see.

Because they’re about things that have happened to me…

Stories about things that have “happened to me” make up the bulk of the poetry readings in the Elko Convention Center. Gentle, good-humored poetry celebrating a highly skilled, dangerous and low-paid occupation. Of course, there is some exaggeration. “Wherever you find a cowboy, you’ll find lying,” Melvin Whipple chuckles. These embellished tales, known as “windies,” are big laugh-getters. “It can get pretty boring out there on the range,” Whipple explains.

While the audience enjoys the windies, it’s the gritty occupational details of life on horseback that really enliven the proceedings. In the hallways of the convention center, young buckaroos in marine blue silk scarves listen raptly as senior citizens with bowed legs and plaid shirts describe difficult and dangerous moments on the range.

“I’m not interested in poetry for poetry’s sake,” announces Duane Reece, a tall handsome rancher. “What’s important to me is the message. It’s dedication to the work. It should be done right.” Reece was born on a ranch in Arizona 47 years ago and has “worked cattle in every state west of the Mississippi.” His poems are all about his trade — the roundup, “the only thing I know about…and people.”

“I’m not interested in poetry for poetry’s sake,” announces Duane Reece, a tall handsome rancher. “What’s important to me is the message. It’s dedication to the work. It should be done right.” Reece was born on a ranch in Arizona 47 years ago and has “worked cattle in every state west of the Mississippi.” His poems are all about his trade — the roundup, “the only thing I know about…and people.”

Reece has a keen eye for the intricacies of cattle herding: “I emphasize the skills” he explains, “because they have been disregarded in recent years. Now there are so many impostors. There are very few bona fide lifelong cattlemen left – it’s all corporations now, people interested in tax write-offs. They have no way to judge their employees. Proper skills aren’t respected.”

Reece isn’t the only one concerned bout the disappearance of authentic cowboys. “Some of these guys here haven’t spent much time on a horse,” laughs one old cowhand looking around the convention center. In response to my obvious question he explains. “I can tell by how they walk, how they talk. Aw, heck, I know just by lookin’ at their faces. I can read ’em like a horse.”

Although some of the rhymes are recited by dudes who haven’t spent their entire lives roping cattle, one type of cowboy is definitely missing. Nyle Henderson draws the wildest laughter with his unflattering description of an urban cowboy:

I sat alone in the corner a sippin’ my beer

When a fellow I didn’t know began to draw near.

Now I’d spotted him once before, earlier that night.

Now he stood there before me. I laughed at the sight.

He looked like a brand new windup toy

I said “I can see by your outfit you’re a cowboy”

Now I can tell you for sure he was really decked out.

It musta cost him a fortune. I have no doubt.

He had on wing-tipped boots and feathers covered up his hat.

He had silver on his belt and all of that.

There was genuine pearl snaps on his brightly flowered shirt.

He wouldn’t a looked funnier if he’s been wearin’ a skirt.

He had on dark glasses and a pair of them designer jeans.

He looked like a picture in one of them magazines.

With a filter tip cigarette hangin’ from his lip.

I guessed he just wasn’t old enough to dip.

But I had to say one thing as I stared at this stranger.

Now he’s what I’d call a real Rexall Ranger.

But accordin’ to what I’ve read every once in a while.

In the cities, fellows like this are now the style.

As he left without makin’ any further intrusion.

I watched him go and I reached this conclusion

That if to be a cowboy you gotta dress like that duck

Well, the I’m gonna quit and get me a job drivin’ a truck.

While more than one cowpoke is moved to tears while extolling his favorite “hoss,” women are seldom mentioned. And when the subject of women does come up, it is not always in a favorable light. One cowhand recites an old poem by the popular Curley Fletcher, one in which women are referred to as “poison” to be strenuously avoided.

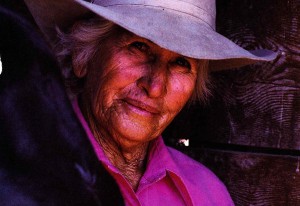

Despite the absence of female “pardners” in the poetry, there are several feisty lady cowpokes at the gathering. George Sicking reads her poems in a hesitant voice, but when she is not in front of a microphone she talks a blue streak. She has a way of conversing about cattle that makes you wonder if anything else is worth talking about. Sicking took her first cowgirl job at 23 and has been working cattle ever since. Now, at 64, she runs her own ranch in western Nevada.

I ask her if there are many other women who ride. “Yes, but ridin’ isn’t the only part. There’s such things as learnin’ to pack a mule, shoein’ a horse, ropin’ a cow and tyin’ her down. There’s a lot to it. Cowboyin’s a complicated business. You have to know animals. Be able to deliver a calf or treat a sick animal. And if you own your own ranch, you gotta keep books and know a bit of law.

After she recited her poem “To Be a Top Hand” (I just about broke my neck tryin’/To be and do/All those things a good cowboy just/Naturally knew), I asked her how other women related to her working the roundup. She said they could be vicious: “When their husbands returned and said what a good hand I was, they’d have to pull me down some way or another. Maybe they’d tell tales of promiscuity, or they’d say, ‘Well, your skin is terrible,’ or ‘You oughta’ comb your hair,’ or ‘You look just like a man.'”

Sicking shrugs it off. “I can handle it now,” she says. “It took every bit of intelligence and strength I had to get where I wanted.”

Widowed ten years ago Sicking recalls that she met her husband at a rodeo. “The day he came after me to get married, I was off ropin’ wild burro,” she laughs, “so we had to get married the next day” She and her husband worked for a lot of outfits before getting their own ranch. “We were always pardners. He was just as apt to be cookin’ in the kitchen as I was. It was just who was handy. And, as far as the kids were concerned, if I had to go work a bunch of cattle, he made sure he stayed close enough to take care of them.”

Georgia Sicking may not reveal her exceptional strengths and skills in her poetry, but Jo Marie Casteel shoots it straight. This 35-year-old rancher from Vale, South Dakota, makes a clear case for why she wants to be treated as an equal, in her poem “Women’s Lib”:

Now I pride myself in being

A vital part of this outfit.

I’m a liberated lady

And I damn sure don’t just knit.

For years, across the country,

We gals have took the brunt

So listen up, dear man of mine,

I’m goin’ to make it blunt!

I do the same chores that you do,

I pull more than my fair share

I pitch the hay and shovel cake,

And I do it with a flair…

After reciting her poem, Casteel tells me that she and her husband, Tom, run a 10,000 acre ranch with 500 head of cattle and 600 sheep and they do it without hired help. It’s only 20 miles from the ranch where she was raised. “It’s all I know” she says. “In our family everybody worked, did everything”

Casteel says proudly that she and Tom are equal partners in everything, “including the decision making.” Tom traveled to Elko with her to lend his support. It’s the first vacation they’ve ever had.

Although she had two years of college, Casteel was never attracted to city life or white-collar work. As her poem puts it:

Now I figure I’m sure lucky

No slave to clock or bell,

And I’m breathin’ all God’s beauty

There ain’t nothin’ I must sell.

“We respect our heritage,” Casteel tells me. “A lot of things they did a hundred years ago we do today, and we are passing on these traditions to our children. Much of Casteel’s poetry is a tribute to a special breed of “rugged individuals,” an affirmation of the values of the old days when there were…

No fences in sight to slow a man down,

Just prairies and mountains galore

The rush of rivers over the land

There is space and freedom and more.

Space and freedom. In cowboy mythology — whether the old dime novel, Westerns, or Marlboro advertisements — the hero on horseback personifies free spirit. He is tough, independent, decisive, his own man. Rooted in partial truths, this mythological hero emerged precisely at a time in American history when government and big business were redefining America. The cowboy was pictured as the last holdout.

The young buckaroos of the New West still cling to this mythic vision. Despite the foul weather, long hours and low pay ($500 a month plus room and board), they drift from outfit to outfit and repeat that they are free: “I may be broke, have only a saddle and a bedroll, but it’s freedom,” says Bill Black, who has worked for 22 outfits in nine years. “I can’t imagine working in a factory or a mine- the same thing every day,” says Waddie Mitchell, who has buckarooed all his life.

But modern America — with its strip mining, corporate cattle raising, missile testing and federal land management — continues to encroach on these cowboy’s freedom. Poet after poet in Elko decries barbed wire fences, longtime symbol of civilization’s restraints. From Melvin Whipple:

The cowboy uttered to his Horse, Ol’ friend the country’s gone

There ain’t no cowboys anymore, Now it’s time we’re movin’ on

Barbed wire fence and pickup trucks rule the range t’day

The Bureau of Land Management has come out West t’stay

A federal man patrols this land ‘nd scouts the grass ‘nd trees

And now barbed wire hems us in, Ol’ Hoss! We’re just not free

The mustangs are gone, the wild horse bands that used t’roam this range

They call it all Progression. There’s nothin’ quite the same…

Whipple, without much formal education, has written about 40 poems, moving tributes to the range pioneers and the values and freedom of the past. After cowboying all his life, he had to give up his Arizona ranch not too long ago and now punches a time clock at a feedlot in Hereford, Texas. Whipple says he hates it. “They don’t know how to treat cattle,” and consequently they don’t respect the skills of the cowboy. A way of life has been lost.

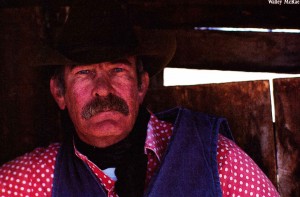

At a noontime panel discussion, several other cowboy-rancher-poets express concern for the “future the cow” — and themselves. The range is shrinking, big corporations are absorbing more and more and some ranches feel that they are only a few steps behind the small farmers. Walley McRae, a third-generation Montana rancher and past chairman of the Northern Plains Resource Council, says cowboys have been too reticent. The council, he says, has helped “us show our rage.”

McRae’s family have been working their land for over 100 years. In recent years, several energy companies wanted to strip mine it. Some of his neighbors have acquiesced, taken the money, and run. But McRae is holding out and fighting back. His angry poem “Crisis” says it all:

In times such as these, in our energy squeeze,

You must try the “big picture” to see

If untempted by booty, then think of your duty.

If you’re selfless, then you must agree;

Our country must grow or the gray faceless foe

Will surely stalk o’er our grave

For Growth made us great. It must not abate.

It’s no monster, you see, Growth’s our slave.

We’ll win in a rout, if we get the coal out.

We’ll all be the winners, you see.

We’ll not freeze in the dark. We’ll continue our lark.

And coal — good black coal– holds the key.

On their shrill voices go. Drifting, sifting like snow.

I resist them with all of my might.

For their cloying sweet song is grievously wrong,

Deep within me, I know that I’m right.