I had been editing scripts at Radio Beijing* for several weeks before I began teaching classes on broadcast journalism for the staff of the English department. I kept notes on the daily broadcast so that the class could discuss problems of content, form and style. In the first class I asked ths staff how often they listened to the final program. The reply was a roomful of puzzled faces.

“How many of you ever listen to the broadcast?” A chair squeaked.

“But if you don’t listen, how do you expect somebody thousands of miles from here to listen?”

I shouldn’t have been surprised, I supposed, when Zhang Qingnian, the leader of the features section, cleared her throat and responded. “The comrades decided a long time ago that the program was boring.”

It was my first indication that there was little that I would have to say about the programming that m Chinese co-workers did not already know.

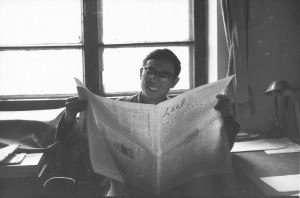

I had also noted that every morning, when I arrived in the office, the workers in both the features and news sections were listening to Voice of America.

FRIENDSHIP

Radio Beijing’s programs about China are beamed at the rest of the world in 49 languages. Each language department hires at least one “foreign expert” who polishes scripts and sometimes announces. The largest departments are English and Japanese. A staff of forty in the English department produces a one-hour daily program of news and features that is rebroadcast nineteen times a day. News is updated every eight hours.

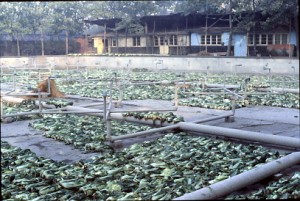

“Friendship” and “modernization” are major themes of both news and features. Reports of scientific and cultural exchanges underscore China’s policy of friendship with other countries while proof that the Four Modernizations are in full swing is provided by reports on the increase in kumquat production in Hubei, the increasing numbers of hydro-electric power stations on the Yangtze River, the use of lasers in medical operations, and the greater availability of television sets and other consumer products. In the course of the hour, peasants are rarely mentioned. Eighty percent of the Chinese are peasants.

A third theme dominates news stories: anti-Soviet hegemonism. One common genre of news story, what I call “banquet news,” usually combines friendship and anti-soviet hegemonism. At these endless banquets Chinese government officials and visiting representatives of other governments give speeches about the threat of security posed by the Soviet Union ad the importance of friendship between the two assembled governments.

The single source of information for the twenty-minute newscast is Xinhua, the New China News Agency, which now has reporters stationed in most world capitals. Not long after I arrived at Radio Beijing, Ma Riuliu, the leader of the news section, sat in the brown plastic-covered armchair next to my desk. “We’re thinking about getting more news wire services,” Ma began, “like AP, UPI, and Reuters. What do you think?”

Ma Riuliu – called Lao Ma, which means “old horse” — is in his early forties. He’s short and peaks with the accent of Canton, his family home He has a big nose for a Chinese and his hair is cropped close. Ma’s eyes, circled by 1950’s style clear plastic-rimmed glasses, fixed eagerly on mine.

“It would provide more variety of news,” I said, “but you know it’s expensive to subscribe to those services.”

I was already painfully aware of the economic reality at Radio Beijing. Despite the heavy heat of Beijing’s summer only those offices in which foreign experts worked have electric fans. The halls were dark. Most comrades used ball-point pen refills wrapped tightly with paper. We used straight pins instead of paper clips. There wasn’t one good microphone available for interviews. There was no Xerox machine available for anyone but the top leaders in Central Broadcasting, the super-agency that runs both domestic and overseas broadcasting. And, I had been told by Ma, that for economic reasons they had never in Radio Beijing’s thirty-year history spliced a piece of tape. As someone who had spent thousands of hours in editing booths with tape coiling in pyramids at my feet, this fact was more significant than any other.

There was also the foreign-currency problem. “I understand it’s expensive,” Ma said, twisting in his chair. Ma was nervous and shy. He had the habit of looking away as he spoke. “We could tap off the machines at Xinhua.”

“I think that might be illegal” I said.

Ma chortled, awkwardly. His mouth twists mischievously to the side of his face when he smiles. Suddenly, he was serious again.

“Do you know how to operate them? Could you teach us to use them?”

“Sure, that’s easy. It only takes a few minutes to learn to operate them. The real problem is that they produce huge volumes of information. Who is going to read all that stuff quickly? And more important, who’s going to make the decision about what to broadcast?”

“Oh, I hadn’t thought of that.” Ma’s laughter was more relaxed less forced this time.

It was an improbable conversation anywhere, perhaps, but especially in China where technology and science hover as a new cosmology over a land where the majority of people still do everything with their hands where a billion hearts and minds have been enlightened by the politics of self-reliance not by the philosophers of industrial progress, and where the question of who makes decisions produces paralysis.

I, who had come from the city of frantic speed, from a culture of risk-taking, from a profession of instantaneous history, at first thought the decision-making sludge in China was a result of two thousand years of bureaucratic practice. “You must be patient,” my co-workers would tell me time and again.

Later, I would understand the overlay of thirty years of tacking between two lines: One line, usually associated with Mao, called for more political participation and social revolution combined with slower industrial development. The other line, associated with Deng Xiaoping agues for faster industrialization and more centralized control. The result was entrenched bureaucrats fearful of decisions that might be judged “incorrect” with the next tack.

Ma and I laughed together and it was this lack of self-consciousness that I grew to love about the Chinese. For all their caution with foreigners, their emotional control, it was possible to have an ego-less conversation with a person in authority. But I would never hear anything more about the wire services.

PITFALLS

About forty minutes of the broadcast hour is devoted to longer features under snappy program titles like China in Construction, Culture in China, Travel Talk, etc.

More than half of these scripts originate from a smoke-filled room opposite the English Department. After only a month on the job I was blaming most of our problems on the group of serious-looking comrades who sat in that room – the Chinese editors.

The scripts emerging form their desks were translated into all 49 languages and were consistently dreadful. They were too simplistic, to the point of cant. Sometimes it was a matter of organization, or arguments poorly developed. There was a tendency to assign equal importance to all information. Occasionally, so many questions were left unanswered that I suspected the script might have the opposite of the effect intended.

Some feature scripts were copied directly from Chinese publications printed in English like Women in China, China Reconstructs, or Sports in China. There is no concept of plagiarism, and so there are no copyright laws. The author of the original article would not be credited unless he or she was in a leadership position, “a responsible member” as my co-workers were fond of saying. No effort was made to check the accuracy of the original article.

Periodically, special features appeared from the New China News Agency. Sometimes written directly in English they were usually more substantial, exploring the complexity of current problems and issues clearly and cogently. They were written in a popular and conversational English, making them more suitable for broadcast.

By far the most interesting and lively programs were those produced by members of the staff who went outside the grounds of Radio Beijing to gather interviews. By the time I left, about one-quarter of the features included interviews done by staffers with visiting English-speaking delegations, prominent Chinese who spoke English or Chinese-speakers who would later be voiced-over.

Most broadcasts had all the classic pitfalls of radio journalism: long, complicated sentences, unnecessary use of the past tense and passive voice, too many statistics and lists. The formal language and print style ensured lifeless delivery. The overall effect was like listening to magazine articles. In fact, program segments usually began with “This is an article about…,” a device that I later traced to Radio Moscow.

While some announcers have pleasant voices, there was little indication that they cared about what they were saying. There was no anchor to connect pieces of the program or speak directly to the listener. For years, announcers were nameless, but a few months after I arrived this changed, to the delight of long-time listeners.

AMBIENCE

Nothing in the ambience of Radio Beijing felt familiar to me as radio. There was none of the electricity of human energy and anxiety that characterizes news and public affairs operations in the U.S. There was none of the excitement that comes as reporters race in and out to cover stories, locate sources, chase down interviews, argue with editors, or fight for access to editing booths. While I was surprised to find so many western character types in the department (the selfless and the selfish, the petty and the kind, the opportunist and the retiring, the mischievous and the cautious), one species of American broadcasting personality was missing: the competitive egomaniac.

I also never sensed the thrill of a reporter who captures the essence of a story in the cadence of a human voice as it articulates an old idea in a fresh way, or a new idea with startling power. There was none of the fear of failure as the clock ticked and you faced miles of tape, seemingly disconnected arguments, and a mass of details that had to be written into an intelligible two-minute report. It was more like rip and read.

There was none of the nervous marathon against the second hand of the clock, but rather a dogged sense of clock time that portioned the day into routines of fetching hot water, cleaning the office, reading the People’s Daily, attending political education meetings, exercising during morning and afternoon breaks, and sleeping away long lunch hours. Several large round clocks hung suspended from the high dark ceilings along the corridors of Radio Beijing. Each one worked for only a few minutes each day. Each pointed to a different time.

Perhaps it is unfair to compare Radio Beijing with the radio environments I have worked in – WBCN-FM in Boston which during the early 1970s had one of the liveliest, most controversial and creative news and public affairs departments in commercial radio; WBAI, the most eclectic of the Pacifica stations, where I had been Public Affairs director. I had also produced for National Public Radio’s All Things Considered, the best news magazine program in the U.S. Of course, these are exceptional even in the American broadcasting scene, but they were my experience, my history. They were my frame of reference in China.

When I listened to the homey tones of Voice of America’s daily news magazine with its smooth vision of American pluralism, I realized that I might have been frustrated working there, too. Yet that is the comparable medium to Radio Beijing. Compared to domestic American radio, Voice of America’s programming is less hectic and diverse; VOA is more cautious and puts more emphasis on the virtues of “the America way.” Likewise, China’s domestic radio programming offers a richer variety of humor, music and information than does Radio Beijing.

QUICKSAND

When I arrived at Radio Beijing I felt like I had hit quicksand at eighty miles an hour. Nobody in the officee would talk about anything going on in Beijing, China or the world. When I asked my co-workers questions about news events, the response was usually silence or giggles.

After several months of complaining about the information vacuum and explaining that it was vital for the development of the staff’s English skills, and consequently for the programming, to discuss current events in English, one of my co-workers ran into the office with an offering: “Gail, a Japanese woman just gave birth to a fourteen pound baby!” I wanted to hug Zhang Wei, but, of course, this was not the news I was looking for. I wanted to discuss politics, economics, and social issues.

Halfway through the year, after I had resigned myself to the permissible conversations about the weather, food, proper clothing for the seasons, and Chinese festivals, one comrade finally had the forthright courage to tell me: “If someone is seen talking to you longer than is necessary to work on a script, someone else may report them to the leaders. They risk losing everything, housing, health care, their children’s education. That’s what has happened in the past. People are frightened to talk too much to you.”

This is the contradiction that foreign experts are confronted with in China. The government invites us to share our skills, then treats us as social lepers. Perhaps that is too harsh. Although the experience varies somewhat, the unwritten rule is “you can’s make friends at your work unit.” People’s Liberation Army guards stand at the entrance to the buildings where foreigners live to discourage Chinese visitors.

There is no sense belaboring this fact of Chiense-foreign relations except to say that it leads to an emotional rawness among “experts.” Tempers flare; segregation, surveillance, and distrust sour otherwise pleasant people; some become alcoholics (two were sent home from Beijing last year with alcohol poisoning); others leave “speaking bitterness.”

Of course in Beijing foreigners can “hang out” together. But I did not go to China to spend my time with Kuwaiti diplomats, Canadian journalists, German students, Sri Lankan exiles, and American anthropologists. However, vital the friendships of these other foreigners became, I sacrificed a progression in my career in the U.S. to have a direct experience – living and working relationships with the Chinese. I wanted to relate to whole people: at work, in their homes, with their families, learning about their ideas, feelings, doubts, hopes and dreams.

Fortunately, the human spirit prevails; despite the very real fear and considerable risks to the Chinese, ”experts” do make Chinese friends and this is the most precious gift we bring home.

But at Radio Beijing my efforts to relate beyond the superficial niceties were blunted. It took some time, however, for me to appreciate that I also contributed to the situation. I was, after all, a journalist form a capitalist country working indise one of the most important propaganda institutions in China. I am outgoing, demonstrative, emotional, talkative, impatient, argumentative – qualities not admired in Old or New China. My own anger at the lack of discussion about world politics or local events often prohibited me from perceiving what some of my co-workers were communicating in subtle ways – about their lives about those things which did concern them, like money, food prices, crowded housing, the generational war, or their frustration about the limits on their own power to change things, to affect decisions, to change jobs or move to another town.

As I look back now, from this emotional distance, I realize how much I learned from that year with the staff in the English department. But in the midst of it, I who had come from the culture of immediate intimacy, narcissistic confession, and the American news industry, felt totally frustrated.

The staff in the English department were hired to be translators, not reporters. They are all graduates of foreign language institutes who were assigned to Radio Beijing upon graduation. In China, there is little job choice or mobility. Upon graduating from middle school to university, people are assigned to a work unit, usually for life.

While there is a training institute for radio and TV workers in domestic broadcasting, there is no comparable training for Radio Beijing employees. Most of the staff never write anything original in English, and have no reportorial skills. Some, who have worked in the department for more than twenty years, have never done an interview.

Division of labor is minimal. There are no secretaries or receptionist. Everyone does his or her own typing and is capable of doing the engineering, too. During the Cultural Revolution engineers were “re-assigned” to less prestigious tasks, as were other technically proficient people. This was part of the challenge to the power of the technocrats. Now, the engineers are back.

In the English department, workers move back and forth between the News and Features sections interchangeably. In the Features section, where I worked, the leader disbursed the Chinese language scripts to the translators, who would be assigned to a program for several months or a year at a time. After the translator types up the English script it would come to me for editing. I sent it back to the translator who then typed up the “good” version which would go to the section leader for final editing and approval before the announcer read it.

Those with the best voices and command of the language become announcers. They are coached by “veteran” announcers who in turn were trained by past “foreign experts” none of whom had any previous experience in broadcasting.

I was the first “expert” to be hired who had broadcasting experience. In addition to editing feature scripts, I conducted workshops on broadcast journalism, interviewing and announcing. I also taught a series of classes on the history of American broadcasting and on “ issues in American society.” The purpose was to improve the staff’s understanding of their competition and their audience – so they might more effectively address that audience.

I sensed that the serious motivation problem had to do in part with a feeling of alienation from the audience.

Although most of the workers had an excellent grasp of formal British English grammar, they had little feel for the living language of North America. When I arrived the department library offered nothing more recent than nineteenth-century English novels. Newsweek was incomprehensible to them (possibly a blessing).

The staff’s lack of knowledge about American society and culture has a number of contributing causes. First, traditional Chinese xenophobia coupled with Han chauvinism helps to shape one of the most conservative cultures in the world. Secondly, the simplistic analysis provided by Party theoreticians about western capitalist countries has led to absurd judgments. For example, the Ministry of Culture has pronounced western classical music good, whereas blues, jazz and roc n’ roll are labeled bourgeois, evil and decadent. Furthermore, with the closing off to the West during ten years of the Cultural Revolution, knowledge of western culture and social trends slipped further into a black hole. Of course, most Americans are equally ignorant of China for many of the same reasons. But people working in news, information or educational services cannot rationalize such ignorance.

In the English department at Radio Beijing, part of the audience problem has to do with listener feed-back. “Listeners don’t usually say anything about the programming” said one young staffer in the Letters section. “They only want their frequency cards confirmed.”

The Letters section was run by four comades who handled a bewildering pile of listeners’ mail.

“Many of our American listeners seem to be fourteen-year-old boys,” said Fan, looking at me as if I was secretly responsible for this peculiar phenomenon of American culture. Shy and nervous, Fan has the sweet, self-conscious demeanor of a sixteen-year-old although she is past forty.

“Americans listen to radio for music and news headlines,” I tried to explain “In the U.S. few people have short-wave radios. Short-wave has been a hobby with young boys since the1920s and is part of the fascination with the technology of radio rather than with the content of programming.

Fan looked at me disappointed. I, too, wished I had a sexier or more radical explanation. Since most radios manufactured or sold in China have short-wave bands, this tiny sub-culture of short-wave listeners in the land of high-tech seemed odd.

In addition to the steady stream of frequency cards that listeners from the English-speaking world sent in for confirmation, there were other puzzling and comical gifts.

“What does this mean?” Fan’s smile was both teasing and tentative as she handed me a postcard of a motel in Palm Springs. I guessed that for someone who has sat in a dusty, cold, gloomy, cavernous office six days a week for twenty years or more without vacations or travel or a sexual revolution, the image of a shiny motel surrounded by palm trees and signs boasting pool and TV must seem surreal.

Fan’s desk was always littered with recent offerings from the other side: photographs of a listener’s children, postcards of churches, a package of Big Red chewing gum, a Catholic prayer with gold-leaf trim on stiff paper suitable for framing, and a card enclosing a five-dollar bill with a scribbled note: “Go out and buy yourself a drink.”

One afternoon as I sat at my desk editing a script about a model worker who sold buttons in Tianjin, the usual office sounds of typewriters, Mandarin gossip and gutteral spitting were suddenly overpowered by the screams of the Sex Pistols. I ran down the hall to trace the source. Walking into one of the large offices, I found eight comrades from the English department paralyzed in their chairs, looking straight ahead as if in deep shock, while a tape deck blasted out punk rock. “It’s a gift form an American listener,” frowned Lao Ma.

INTRIGUE

Another “audience” dilemma had to do with the weekly program Travel Talk. The script originated from the Chinese editorial department. The translator, Yan Aizhen, had never been to any of the places she was describing in English. Yan had a rare sensibility for English and consistently produced the best translations throughout the year, yet the final products were often embarrassing. Part of the problem is the different sensibilities of eastern and western cultures. For example, the Chinese are fond of exact measurements of structures and relics, yet the scripts seldom described a local inhabitant. Westerners who travel to non-western countries are usually intrigued by local culture, tradition, dress, food and crafts, as well as information about accommodations, which few of these scripts included.

Because Yan was such a superb translator, I began to appreciate some of the problems of translation. The Travel Talk scripts often included poems by famous Chinese scholars who used to roam the country leaving behind romantic lyrics about China’s scenic wonders. The richness of their poetry comes from the ambiguities and images of the ideographic characters. The literal translations into English are pretentious and, by now, a form of verbal kitcsch.

Furthermore, Yan had a problem shared by the other translators: Since they had not originated the script, they could not answer my requests for information essential to improving the piece. Our efforts to send the scripts back to the original reporters for more information were futile.

If it was a local story, our leader, Zhang Qingnian, along with the translator, would spend hours tracing down more information. The result was usually a remarkable improvement over the original. One of the Chinese puzzles for me was why the Chinese editorial department was allowed to continue such low-quality production. While the reporting of the magazines China Reconstructs and Women in China, for example, tends to be amateurish, it is still superior to that of Radio Beijing.

Yan Aizhen seemed caught in a sad irony. The Travel Talk program was meant to lure tourists to China as part of the new opening to the West and the need for a lucrative tourist industry to generate badly needed foreign currency. Meanwhile, Yan, like most Chinese, has neither the money nor the time off from work to travel within her own country, to say nothing of the hard currency, passport and time needed to go abroad.

The absence of annual vacations, however, does not mean that Chinese workers do not take time off. I was always fascinated by the ways in which my co-workers made “down time” for themselves: perhaps something as simple as goofing off in the office, gossiping or slipping out to do some grocery shopping or get haircuts on company time, or taking sick leave for a simple cold, which could become months for an operation or a family funeral.

Unmarried workers are given twenty days annual home leave to visit their families in other cities during Spring Festival. And time off is also granted to married people with sick family in other cities.

In general, I was impressed by the organizational “caring” for the welfare of workers. One staffer whose husband was abroad studying was sent to the hospital for an emergency operation The department organized a constant vigil at her bedside during the first week after the operation. When another comrade stayed at home for a month or more after one of her parents died, she was visited regularly by a representative of the department.

There is a fine line, however, between the welfare benefits provided by the work unit and the potential for control over the workers’ private lives. In China, the work unit organizes and distributes health care and housing as well as ration tickets for staple foods and consumer goods like bicycles, sewing machines, stoves, and TV sets and even tickets for performances and films. The work unit also grants permission for marriages and divorces.

In state enterprises and agencies, bureaucracy combined with scarcity has inspired corruption and favoritism, in the form of guanxi (I’ll scratch your back if you’ll scratch mine) or houmen, the “back door” (connections necessary to get almost anything). The severity of these types of abuses among Party cadres has led to widespread disillusionment.

As one bright young worker in the English department said, “Gail, it doesn’t matter how hard we work, or how long or how good our work is, what matters is that we get along with the right people.” A bureaucratic truth under any system, except that in China even the corner grocery is part of the bureaucracy.

If I found the lack of enthusiasm among the staff disappointing and the ineffectiveness of much of the programming troubling, the department leaders seemed locked into a frustrating situation. By and large, the middle-aged intellectuals of China are engaged in a tough battle. They are the ones who have devoted a lifetime to building New China, have been victimized during periods of “purification,” and now look behind them to a younger generation that is less educated and more disillusioned as a result of the Cultural Revolution and its aftermath. On the other hand, these cadres have difficulties with those above them.

Zhang Qingnian, the leader of the Features section, had been to college in the United States and chose to return to Beijing after Liberation to help create New China. She worked overtime every day. Along with other department leaders, she was trying to implement changes: sending young staff member to study journalism in the U.S., directing staffers to do more interviews and to originate more creative programming. Several times she said to me, “Please put your criticisms in writing, so we can give them to the top leaders. Maybe they will listen to you because you are a “foreign expert.” They do not seem to listen to us.”

I also saw the frustrations of the younger staff members who felt there was little real opportunity or incentive for them to explore their creative potential, or to affect decisions in the department. Several had been sent to Canada or England to study for two years during the early 1970s. Since their return they have had little opportunity to put into practice what they learned.

TALENT

China is bursting with talent and self-confidence. There was Li Shutian, a forty-year–old graduate of Nankai University, whose desk bordered mine. Li produced the Learn to Speak Chinese program and was working on an accompanying textbook. His comprehension of linguistics and the English language, especially considering that he had never lived in an English-speaking country, was astounding.

There was Su Xiangming, one of the best announcers, who had worked in the department for more than twenty years. She had never done an interview. Last spring she did the first group interview on China’s national TV station for the Sunday English program. Questioning half a dozen Public Broadcasting Service executives from the U.S. she did an excellent job.

There was twenty-three-year-old Sha-Sha, one of the youngest of the staff, who simply picked up a tape recorder and a microphone one day and went out to interview a group of visiting American sociologists. She had never interviewed anyone before and the result was impressive.

Then there was Wang, a forty-year-old bachelor, a rare species in China. Wang spoke not a word to me for six months “He’s shy,” said Li Shutain. “That’s why he’s a bachelor. He was in love once but he was too shy to tell his girlfriend.” One cold December afternoon after a lunch hour shopping trip, I returned to the office with a harmonica I had bought. “Who knows how to play?” I asked. Up jumped Wang to play the most soulful renditions of “Red River Valley” “Home on the Range,” and “Aulde Lange Syne.” His feeling and skill at the harp were so powerful we asked him to play again and again. Wang was also an exceptional translator.

During the past couple of years, staffers have been sent to Japan, England and the U.S to cover sports events and even to downtown Beijing to cover, again for the first time, the National People’s Congress. And they’ve done fine jobs. There are, of course, others in the department who have no inclination for radio or reporting at all.

If modernization is going to be more than a slogan, there will have to be some systemic changes: more job mobility, an educational system that nurtures more creative and critical thinking and working environments that provide more leeway for experimentation, for creative expression and for risky decision-making. China has, perhaps, the greatest story of the twentieth century to tell. While western scholars have helped us to understand some of the moments, it is finally a story which can be told only by the Chinese. Radio Beijing and other propaganda agencies have an enormous responsibility. But if the workers themselves cannot stand to listen to their own telling of that tale, how can they expect that anyone else will?

*In 1980 we still used “Peking,” not “Beijing.” However, to be politically correct I have used Beijing in this printing of the article.

Hi Gail, read your article with great interest. What an amazing career you have had. My husband and I visited China in’87. We loved the trip, but realized we were just shown a certain aspect that they wanted to showcase. We had a young local guide who gave us great insight into his own up bringing and life for his parents and their families.

Hi Gail, I was one of the British airways crews that took the early BA flights into Peking. We only had a short stay (hours) then (1980) but I had to go and experience Peking as it was. My memories of the airport car park was that it was full of bicycles, thousands of them. I think I saw maybe ten cars total, all looking more like 1930’s vehicles. Every one was wearing either a Khaki green or blue suit, without exception. Some students had come to the airport especially to try and talk some English so being in BA uniform I was an easy target. Within minutes I was swamped by people as if I was a film star, all wanting me to say something in English! When I did it went deathly quite as they listened. I felt so embarrassed, I

Thank you, Steve, for these impressions. Wonderful! I am just about to publish a memoir from my year working at Radio Beijing, so stay tuned! You can see a little excerpt from it on my website under the title “China in a Box – Memoir” Thanks again for taking time to visit my site and add your experiences…Gail

I am going through my China slides – ready for digitalisation – and was checking up some details when I found your article which I think is a very accurate account of what it was like to work in Radio Beijing. I worked there from 1978-1983 helping to set up a local radio station for foreigners and remember you for two things in particular: one of the foreign experts offered to carry your case when you arrived and you were not pleased making it quite clear that you could carry it yourself(!) and I remember you complaining that you had taken some photos of the local area which the Chinese did not like as they thought they did not show China in a good light. I remember thinking [maybe something to do with coal] that they were good photos of actual life which no-one should be ashamed of. I am retired now but have very fond memories of my time in Beijing and of the friends I made there. I too went back and visited the new radio building in 2006 with my daughter Lulu, who was born in Beijing, and we met up with former colleagues. It was while trying to find a photo of the old radio building [which I haven’t yet found] that I came cross your article. My one regret is that I had a very basic camera so my photos are not as good quality as yours.

Hello Yvonne, I am sorry for the delay in responding to your comment on my archival website. Thank you for being in touch. Which language department were you in? Somehow I have no recollection of the first incident you report here about my behavior (!). I wrote a memoir about my time there “Forbidden Fruit: 1980 Beijing” published in 2016 in which I describe my arrival and that incident escapes me. But it is all so long ago now. I was able to write my memoir because I kept detailed journals and copies of all my letters home. i will write a personal note to your email so that you will have mine, if you’d like further communication. Best, Gail