The $100 million music that’s bigger than jazz, classical, soul and gospel

I AM DRIVING ALONG a freeway in northern New Jersey, a landscape of petrochemical time bombs. It’s late afternoon and raining. The traffic moves like sludge. I search the AM only dial on my rental car and hit on a heavy funk up-tempo beat with a woman’s husky belting, the lyrics drowning in layers of good-time rock. The DJ says something about Bonnie Bramlett and I feel thrilled that old familiar rock names are still stirring my juices. A heavy-metal band begins, guitars careen and buzz, rhythms crash around me, evoking Led Zeppelin (if you’re over 25) or Iron Maiden (if you’re not), Voices shriek beneath dozens of track overlays and I’m relieved when the final bars segue into a new wave piece. Now a woman’s punky voice drones pleasantly above the tantalizing beat. She sing-talks something about privatized lives so I remember to listen for her name. The perky DJ yodels that this is Sheila Walsh, the hottest Christian singer in England. We’re listening to Top 40 Christian rock radio, Hackensack, N.J.

While the music biz occasionally buzzes with news of the latest religious conversion – yes, there are others besides Bob Dylan, like Bonnie Bramlett, Maria Muldaur, Phillip Bailey (Earth, Wind and Fire), B.J. Thomas (“Rainbows Keep Fallin’ On My Head”), songwriter T-Bone Burnette and members of U2 and Kansas — the real news for us seculars is that the fundamentalists have been moving into rock n’ roll.

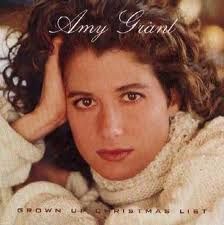

You’ve probably heard of Amy Grant. From The New York Times to Rolling Stone, Grant has been getting good press, reporting her Grammy’s album sales and concert hall sellouts along with her attitudes about sex (okay in private with your husband). At 24, she is the biggest selling artist in the field; her eight LPs have sold more than 3 million copies and her “Age to Age” album is now platinum. Grant describes her music as “pop, rock and ballads that happen to have Christian lyrics.” The Christianity is low-key, Jesus and God are rarely mentioned.

Buy there’s more. Grant is just the tip of a religious iceberg in the rock ‘n’ roll sea. Swelling beneath the surface is a “genre”: a marketplace phenomenon and ideological subculture. Referred to in trade publications as Contemporary Christian Music (CCM), it’s called Christian rock on the streets. These days it outsells jazz, classical, black soul and traditional gospel.

Two major labels and numerous smaller ones claim a $100 million–a-year business in CCM with rosters of more than 80 artists and groups whose musical styles echo every idiom of pop music from soft-rock ballads to heavy-metal guitars, from Latin funk to punky new wave.

Christian rockers who five years ago were playing in churches in the Bible Belt states now sell out 6,000 to 12,000 seat auditoriums from Oakland to New York. They record in the best studios of Nashville and L.A., New York and London, use some of the most sought-after producers and are booked by some of the feistiest promoters in the business. From staging to album covers, synthesizers to PR, Christian slick is indistinguishable from secular slick. Of the 1500 Christian radio stations in the country, almost all play CCM some of the time and about 50 have adopted a Top-40 format featuring CCM between teaching and preaching.

The CCM scene even has its own glossy monthly, Contemporary Christian Magazine, which reviews Christian artists, albums and rock videos and lists rigorous concert tour schedules. It’s here where you might find an ad for Stryper, the heavy-metal band that slogans itself as “Heavenly Metal for Righteous Headbangers.” Another ad promotes a three-day festival featuring “22 bands on 3 stages…the full range of soft rock, new wave, heavy metal sound …plus 80 hours of teaching.”

A less righteous publication, Performance, which carries concert news for the pop field has been tracing the ticket sales success of Petra, which along with Amy Grant, is poised to storm the secular pop market.

With six albums under its belt, combined album sales exceeding $1 million and a 55 –city national tour this year (in many 10,000 seat venues), Petra is the first CCM band to sign a distribution contract with a company definitely not listed in the Christian yellow pages. A & M records. Petra’s members use the latest in sound equipment, computerized lighting, smoke on stage and aggressive booking by the same promoters as the Police. Petra’s competition, says former manager, Mark Hollingsworth, is not so much Amy Grant as the pop bans their music is compared to – Foreigner, Journey and Styx.

Petra’s songs skip the subtlety. They are direct in their pop lingo, rush-to-salvation message, like these lines form the title cut of the group’s album “More Power to Ya”:

More power to ya, when you’re standing on his word

When you’re trusting with your whole heart in the message you have heard

More power to ya, when we’re all in one accord

CHRISTIAN ROCK BEGAN in the Jesus People movement of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, when Christian pop culture exploded into music festivals, beach baptisms and Broadway musicals like “Jesus Christ Superstar” and “Godspell.” As with every change of form and pace, there were movers and shakers. One of the most central to the emergence of CCM was Billy Ray Hearn who in the early 1960s introduced folk guitar to the Texas church where he was choir director. Later he added drums and electricity.

A decade later, by then working with Word (the largest Christian music company) he formed the subsidiary Myrrh label to nurture rock ‘n’ roll. Word signed up grant in 1976 and the rest is music business history; CCM now accounts for 85 percent of Word’s business.

Hearn left Word to form his own communications company, Sparrow, and in nine years since has built it into the largest independently owned Christian music company (Word is owned by ABC). About the new music he nurtured, Hearn says, “The lyrics are about life from a Christian point of view. They promote Christian values and a Christian life style.”

But which Christian values? Which point of view There is a passionate ethical and ideological debate raging within the Christian community these days and a staggering range of political activism in the name of Christ, from bombing abortion clinics to opposing Reagan’s policies in Central America, from banning books in schools to supporting farm workers in a dispute with Campbell Soup Co. It’s an ideological struggle over how to view the church and the world and the relationship between the two.

There’s no such debate among the Christian rockers, whose world, virtually without exception, is that of fundamentalists and conservative Christians battling liberalism, humanism and evil under the banner of the Lord. Petra’s “More Power to Ya’ album focuses almost entirely on this holy war. The cover design depicts space-age war. The song “Stand Up” calls the faithful to battle.

The battle cry is getting louder,

The countdown’s close to the final hour

The enemy is on every side

But still no match for the

Crucified

Victory unto Victory

We are soldiers in His army

Stand up. Take a stand for Jesus

Stand up. So the whole world sees us.

“I’m pretty conservative,” says Bob Hartman, lead vocalist and songwriter for Petra. “I consider myself fundamentalist in beliefs…an evangelical.” Ideologically, the fundamentalist view is antiabortion, antigay, anti-humanist and anti-evolution among other things.

Steve Taylor, one of the most creative lyricists in the CCM field, writes songs to new-wave music that oppose gays and abortion as well as address other fundamentalist concerns like the ethical flabbiness of the church, media and public schools. From his song, “Meet the Press”:

Meet the Press,

When the godless chair the judgment seat

We can thank the godless media elite

They can silence those who fall from their grace

With a note that says “we haven’t the space’

A Christian can’t get equal time

Unless he’s a looney committing a crime

If Taylor’s lyrics are more politically direct than those of CCM artists who are gearing up for the pop market, he shares a tone with all of them that is part of the fundamentalist appeal: a sense that modern society has failed to deliver us whole. Amy Grant’s lyrics allude to materialism, alienation, the loneliness of privatized lives and the loss of the spiritual, a bundle of concerns shared by traditionalists, humanists and many left-liberals.

But then fundamentalists go their own way. Petra’s songs echo the general fundamentalist position that something has gone terribly wrong in our times. Evil abounds.

Redeeming the time for the days are evil

The whole world’s in such upheaval…

There is a way that leads to life

The few that find it never die

When the end comes, the fundamentalists will shoot straight up (during something called the Rapture) and be saved. The rest of us will melt. Picking up on that theme., Taylor’s recent album is called “Meltdown.” Its title cut “Meltdown at Madame Tussaud’s” describes how all the wax replicas of secular heroes will melt into each other. “There they go down the same drain.”

Despite the preoccupation of many Christian rockers with Jesus’ imminent return however, they don’t hesitate to invest in sophisticated video and sound equipment just in case there’s time for a little more evangelizing, a little more music-making before the end comes. And despite the shortcomings of the modern world that many of their songs decry the singers of those songs clasp pop music commercial styles in firm embrace.

SO WHAT HAPPENED to all those fundamentalists who used to burn rock ’n’ roll records? Are they now eating the placards that once read “Rock is the devil’s music?” Well , yes…and no. One of the toughest critics of rock ’n’ roll in the 60’s was Bob Larson, who wrote several books damning the devil’s music. But Larson has changed his tune. Now he writes a regular column for Contemporary Christian Magazine.

Larson, host of a two-hour daily live satellite radio talk show (“with the largest radio audience in America”) says he still sees most secular rock as “rank hedonism.” Once critical of the immature Christian rockers, he now feels they have developed their talents to such a degree that “their poetic seriousness is more profound than anything you’ll find in the old hymn books.”

Petra defends what it’s doing in its PR kit by citing Psalm 33:3 “Sing unto him a new song, play skillfully with a loud noise.” The band’s concert notes include the Scripture that motivates each song. “We’re missionaries, and missionaries, must learn the language of the people they are trying to reach,” Petra songwriter Hartman told Christian Contemporary Magazine.

“We spend part of the concert in worship,” the 35 year old ex-Bible study teacher says. “We have counselors available for kids who want them.”

Larson argues that the typical Christian rock concert is entertainment, not workshop, but says that doesn’t invalidate it. “There’s nothing wrong with Christian entertainment,” he says. “Any effective religion has always been entertaining.”

BUT CAN CHRISTIAN rock reach beyond the already convinced? Rock ‘n’ roll has at various times represented rebellion: against parents, school, ,authority and war. Its greatest rebellion has been against the sensual straitjacket of white Protestant America. At base and at its best, rock ’n’ roll is a celebration of human sensuality.

This quality seems to trap fundamentalist rockers in a form-function dilemma. It is the music more often than the lyrics that makes our juices flow on turnpikes; it is the music that defines what we mean by rock ’n’ roll.

Larson explains that for conservatives and fundamentalists, social dancing between men and women is taboo. “Erotic gesticulations to attract partners of the opposite sex are wrong.” When I ask him about the thousands of young kids who leap to their feet in a Petra concert to clap and shriek, he says “Movements before the Lord are different.”

DESPITE his tolerance for Christian rock, Larson draws the line at Stryper, a heavy-metal band of four guys in their early twenties form the L.A. bar band scene who have found Christ but still appear in early Farrah Fawcett hairdos and skintight costumes.

Robert Sweet, Stryper’s 25-year-old drummer, concedes they are called “low-life scum” and “trash” by some of their Christian critics. But he is unfazed. “We’re here to rock ‘n roll and have a good time,” he says. “You’re not supposed to have a lousy time with Jesus…We’re metal missionaries. God has laid on our hearts to look and play the way we do with this message.”

The fact that three-quarters of their audience is women doesn’t imply the group is “sensual,” he says. “Jesus drew a lot of beautiful women to his side.”

More than any other band, Stryper is pushing to its limits the question of whether Christian rockers can de-sensualize rock ’n’ roll by adding fundamentalist lyrics.

Played by whites for white audiences, Christian rock is bleached from the roots of rock ’n’ roll – spiritual roots, in point of fact. The name rock ‘n ’roll came from the Southern Black church, where the musical expression itself drew partly from West African cultures that did not separate the spiritual form the secular, the spirit form the body. It was Christianity, and more particularly white Protestant fundamentalism, that wrenched apart what once was an integrated whole.

Significantly, musician converts from the pop world (both black and white) often look to Black gospel when they turn to religious music-making. “I was literally zapped by the Holy Spirit during a laying-on of hands at a Black pentecostal church in L.A.,“ says Maria Muldaur of her conversion five year ago. She now expresses her beliefs in “black bluesy gospel. It’s the most spiritually rich music I know.”

For Muldaur, Christian rock is too bland. “They are so subtle in their lyrics that you don’t know whether they’re singing to the Lord or a boyfriend,” she complains. “It’s so watered down. What I like about old-fashioned gospel music is it calls God by name.”

Rock has been fed by many tributaries: gospel, blues, rockabilly country, western, folk, jazz, salsa and reggae. It is constantly pulling from authentic traditions rooted in experience an experience that also sometimes includes the spiritual. Fundamentalist rock, if it is “just a communicative tool” (as Billy Ray Hearn justified it), misses this authenticity.

The stompin, swinging, swaying, yelling kids of Petra’s concerts may be an “ecumenical breakthrough,” as Bob Larson pronounces them. The music that turns them on, to quote Larson further, may indeed be strengthening the fundamentalist world with “a kind of revivalism that couldn’t be accomplished any other way.”

But somehow the nonconvert listener doesn’t hear in Petra or the other groups rocking and rolling in Christian radioland what seems so plain in much of the music of the pop world’s converts – Muldaur or Bob Dylan or Johnny Cash or Little Richard or Arlo Guthrie or the more mystical Van Morrison. Unheard is the ambivalence between the spiritual and the sensual, the sacred and the secular, that may be sprawling an original religious music for our times.

For me, out on the freeway, surrounded by dark satanic chemical refineries, I will continue to search my radio dial for the best of rock ‘n’ roll that affirms my sensuality in the midst of a consumer and militarist culture bent on destroying it.