One Dies Before The Other

The fall light is fading in Renate Sami’s book-lined apartment near Savigny Platz in Berlin’s former West Side. Sami is fiddling with her DVD player so that I can watch her film – “A Year/Ein Jahr” – that will premier this Monday, Oct. 10, at the New York Film Festival – part of a weekend long screening of avant-garde films. “It’s only 12 minutes,” she muses. “A year in 12 minutes.”

“A year/Ein Jahr” is a delicate, simple piece shot on a Handy Cam through Sami’s kitchen window. Two trees. One a chestnut. The other, a maple. The seasons change. The trees are in her courtyard, quite ethereal, up against an eroding grey stucco wall. It’s stark at times, lovely at others as the seasons’ light changes. Natural sounds from the courtyard – construction workers hammering, and drilling, voices echoing, a radio somewhere, birds, and classical music playing in Renate’s apartment. “It’s all simply recorded by the in-camera microphone,” she claims.

“I started to film in early spring and went on through summer, fall and winter. The tree put on leaves and lost them. There was sunshine and rain, hail and a storm, snow and there were birds: I saw a sparrow and heard many others; I heard a blackbird, a pigeon and some crows. There was faint music sometimes and a church bell ringing from very far. And suddenly one evening behind a window that had always been dark a lamp was turned on and off again.”

Sami breaks the sound and visuals suddenly by silent cuts to black. “It’s similar to a poem,” she says. “I think we hear more when you have silences in between.’

Renate Sami didn’t become a filmmaker until she was forty. She grew up in a working class family in Berlin, never thinking for a moment about making movies. She never went to film school. She was ten years old when the war ended. Coming of age in a war shattered Berlin, whether conscious at the time or not, she did what many German women her age did, left the country married to a foreign man. At eighteen, she married an Egyptian, moved to Cairo and raised a child.

When Sami returned to Berlin in the 1960s she studied English and found work translating poetry, articles and books. She says that her awakening happened in the late 1960’s when she visited New York for the first time. There she stumbled into avant-garde artists: she met Ellen Stewart from La Mama, heard the music of John Cage and met Irene Fornes, the playwright.

“I didn’t begin making films until after I got out of jail in 1971,” admits Sami.

Jail? How does that figure into motherhood, poetry and the avant-garde? Sami explains: When she returned to Berlin after those few critical weeks in New York the anti-Vietnam war movement was exploding. She – along with thousands of others – were demonstrating against the U.S. bombing of Cambodia. At one particular protest after the killing of 4 Kent State students by U.S. National Guardsmen “there was an event in Berlin where molotov cocktails were thrown at an Amerika Haus. The police began rounding up dozens of people. I was arrested on my way to a pub.” Those arrested were “in detention while awaiting trial.” All the charges against her were eventually dropped . But it was a year of her life.

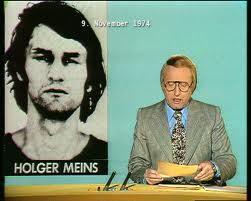

One day while in prison, Sami was taken into a courtyard for exercise. “I heard someone calling my name. It was Holger Meins – calling from a barred window. He was a student filmmaker whose work I greatly admired.” It was shocking to see his face behind bars. He was charged with terrorist activities because of his association with The Red Army Faction (Rote Armee Fraktion) referred to in the media and by the police as the Baader- Meinhof group. (Members always referred to themselves as “The Red Army Faction” which they considered a party or movement, while the police designation of “Baader-Meinhof” was meant to demean them as a terrorist gang.) Holger Meins eventually died in prison while on a hunger strike. Thousands came to his funeral. “I made my first film about him,“ says Sami. I used the funds that the government gave me for my “wrongful imprisonment.”

“I couldn’t believe that this quiet, thoughtful young student could become a violent revolutionary,” says Sami. “He had been a painter before he became a filmmaker. He had produced a very important film about homeless people in Berlin. I wanted to know how that kind of person becomes radicalized and moves toward revolutionary violence. So I decided to make a film about him. I couldn’t interview him – that was forbidden by the prison authorities — but I interviewed many of his fellow students. It was very revealing…I was exploring how people get caught up in political movements for many different reasons, from many different perspectives.” Many of Holger Meins’ fellow students, whom Sami interviewed for the film. have since become leading experimental video artists and well known filmmakers.

“They were all very attracted to him,” Sami adds. “I wanted to know why he had joined this group. It was a time when the student movement was splintering into all of these factions. Many were influenced by guerilla movements in Latin America and were opposed to an increasingly intolerant police state that was emerging in Germany. Some activists chose violence. I think you had the same thing in the United States.” Sami moved into a commune and continued to do political work with a loose group called “Rote Hilfe” or “Red Help” (named after a group in the 1920s). “We published letters from prisoners, protests of the lawyers, and announcements of the hunger strike, etc. Today, there are still people in jail who have never been charged.”

Sami’s next film was radically different. A science fiction fantasy taken from a Ralph Ellison story combined with an indigenous myth about a woman who becomes a jaguar. “I was reading a lot of Levi Strauss at the time.” She laughs. This film was popular with the critics but not commercially successful. It’s now in the art House film archive in Munich.

Since those early films, Sami has gone on to make numerous documentary and experimental films – combining intimate diary-like visuals with text – often poetry — and music. They are personal and idiosyncratic. “Sometimes I’m inspired by a subject, a view, a sentence and the film grows from that.” She shoots on everything from 16 mm to Mini DV. She has also worked as co-producer or director on other colleagues films.

For almost a decade Sami, together with experimental filmmakers, Ute Aurand and Milena Gierke, curated weekly screenings in Berlin of an international range of avant garde and experimental films. Now she is looking at footage she shot in Tangiers in the 90s when she was pursuing an idea about Jane Bowles, a largely neglected story-teller and playwright. “I shot lots of simple road-movie type footage around Tangiers and met with Paul Bowles – her partner. Now, I see it all with different eyes and I want to do something with it. We’ll see.”

Sami hands me a quotation from the critic and author, Victor Schklovsky, that has inspired her thinking about her work and although I am in Berlin to study German this is beyond my capabilities. She roughly translates:

“To make us perceive life again, so that we can feel things again, feel the stoniness of stone, we have something called art. Art aims at giving us a feel for the thing. A feeling that is seeing and not only recognizing.” (Art as Technique)

The sun has almost set and I am thinking about the two trees which I can still see out her kitchen window… splendid in this Indian summer – late September in Berlin. In her film, one of the trees dies much earlier than the other as fall turns into winter. I am struck by how a younger person might not have the patience to see this. And I am thinking about the meaning for Sami’s generation and mine. And how our experiences may vary yet our perceptions about life may converge as time passes. And one dies before the other.

New York Film Festival Views From the Avant Garde Series

Monday, October 10, 1:30 pm

Francesca Beale Theater, Lincoln Center

© Gail Pellett, October, 2011

Thought provoking and lyrical article. Never knew this history about Holger Meins. Makes you want to see the film…

what a great story! I love the “no film school” part, the mere drive of the woman who is then swept up in the dramatic history of her time – right at the center of it, with her camera. And then makes the most of it!

Great story. I’ll definitely watch the movie.

Renate Sami the most sympatic person i ever met.

Sören from Denmark

Hello! ekeeeac interesting ekeeeac site! I’m really like it! Very, very ekeeeac good!

An insight into people and a situation I have not read about. Now to research Sami more!

The greatest wohmen i ever met.