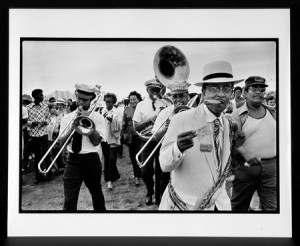

The Dirty Dozen Brass Band, with its signature “half beat, heartbeat, hip-grinding, belly-rolling kind of shake ’em up beat,” has helped revive the street-dancing brass ensemble sound in New Orleans.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS AGO New Orleans was midwife to the birth of jazz, a freewheeling sound that since has spawned a growing family of genius. The offspring have scattered and transformed the sound through so many bloodstreams that some jazz buffs have forgotten the music’s Louisiana ancestry. But the street parade tradition where it all began remains alive and well in the music of the Dirty Dozen Brass Band, a group receiving international acclaim for its reinvigoration of the granddaddy of jazz.

The street bands of the Crescent City have been marching in parades and funerals, playing at picnics and rallies since before the turn of the century. Ensembles such as the Olympia Brass Band which celebrated its 50th anniversary last year, have been blowing their up-tempo rhythms and down home tunes in New Orleans streets whenever anybody in the neighborhood organized an excuse – which could be several times a week. The Dirty Dozen musicians grew up in this atmosphere, where a funeral is both a party and street parade, a joyous celebration of life in the face of death – an attitude that seems to drive much of New Orleans culture.

The music of the street bands however never traveled much beyond the boundaries of New Orleans. Now the Dirty Dozen has taken that traditional music, updated it, experimented with it, and broadcast its unique sound far beyond the city limits. In 1984 the musicians packed clubs and concert halls throughout the United states and Europe and recorded their first album., My Feet Can’t Fail Me Now, named after one of their original tunes.

During the reign of be-bop and cool jazz in the ‘50s and ‘60s, the brass band faded in importance but endured in the parades of New Orleans. When Danny Barker, an accomplished banjoist and jazz historian began organizing young boys into marching bands at the Fairview Baptist Church in the late 60s, he spawned a new generation of enthusiast for this quintessential dancing music.

The Dirty Dozen musicians, all in their 20s and 30s, were members of Barker’s bands. They also come from musical families. They formed the Dirty Dozen in 1978, a regrouping of an earlier kazoo band that played at the Dirty Dozen Social and Pleasure Club. In New Orleans the neighborhood social clubs hire bands for picnics and other functions, and club members contribute to the syncopated footsteps in street parades.

Gregory Davis, trumpeter and spokesperson for the Dirty Dozen, was a music major at Loyola University in New Orleans when he joined the band. He says the what distinguishes the Dirty Dozen is its mobility. The band takes jazz into the streets and gets people moving. He explains:

“Dancing stopped when bebop came in – because of the tempo. When the cool era arrived, everybody was sitting. That’s when R & B (rhythm and blues) became the dance music and jazz was for listening. But we’re a jazz band that you can listen to and dance to.” For example, Davis recalls a concert in Berlin:

“We followed Buddy Rich’s big band…By the end of the evening 5,000 people were dancing. And they brought us back for three encores. We came in playing right on the auditorium floor, rather than on stage.”

Playing the Dozens…

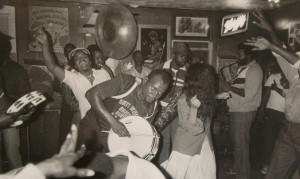

This intimacy between musician and dancer characterizes the street band tradition. In the funeral parades youngsters and old folks gyrate down the street in and around members of the band. In the Glass House, a tiny club on South Saratoga Street in New Orleans, the Dirty Dozen has played every Monday night for several years, wailing right next to the dancers.

The Glass House is not recommended for the timid. Located in a tough and economically depressed neighborhood, it sometimes has offered more excitement than its patrons bargained for, but here musicians soar with dancers. The scene is joyous, gymnastic and wild.

The phrase dirty dozen derives form a game called “playing the dozens.” Two contestants abuse each other with clever and cruel insults. One wins when the other breaks down or replace words with blows. At the Glass House rhythm has become the challenger. How many ways can one move to the beat? Musicians and dancer move together, joined in a community celebration.

The eight members of the band (two saxes, a trombone, two trumpets, a tuba, a snare drum and a bass drum) create rhythmic intensity in a tightly connected ensemble. Davis explains that the beat is unique to New Orleans and the marching-band tradition, emphasizing what normally is the offbeat. “the tuba has a lot to do with defining that beat,” he adds.

New Orleans musicians trace that beat to African drum rhythms forbidden during slavery because they were considered too dangerous. Danny Barker describes this New Orleans rhythm as “a half beat, a heartbeat, hip-grinding, belly-rolling kind of shake ’em up beat.”

The Dirty Dozen has done more than revive the street-dancing brass ensemble sound. Its members have updated the tradition by integrating arrangements of Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker and Thelonius Monk into their repertoire. And their phrasing pays homage to other jazz greats such as Miles Davis. Much of this sophisticated arrangement has been the inspiration of saxophonist Roger Lewis, who played with Fats Domino’s band before joining the Dirty Dozen. Despite the superb solos of Lewis and trumpeter, Davis, however, the band is not a vehicle for single egos. Its members have preserved the collective harmonies of the traditional bands and skillfully pushed the hard-driving beat, says Davis:

“Look, we all grew up with a rich R & B tradition, progressive jazz, and street bands, so we wanted to bring all of that together, and we wanted it to be dance music…We added season and pepper. We experiment with the rhythm, the tunes, and the chord changes.” To charges that the Dirty Dozen has increased the tempo of old street standards, Davis replies:

“It’s just that the traditional street bands began to sound slow compared to disco and R & B. But that traditional music was always up tempo. We’re simply putting more life into it.”

And how did the old street-band musicians react to hearing a Charlie Parker tune played in a funeral parade? Davis recalls:

“They were very critical. They said, ‘You’ll weaken the tradition. You can’t do that to the music.’”

But the test was on the streets of New Orleans, and success came when people liked the up-tempo innovations. National and international recognition followed, as did a revival of traditional jazz. According to Davis there were only four working street bands when the Dirty Dozen began. Now that number has tripled.

In the past year the band has performed at jazz festivals and clubs throughout the United States, Canada, Japan, Europe, and the Caribbean. Their second album, a live recording of a performance at the Montreux festival in Switzerland, should be in stores before the end of winter. How do these young musicians feel about such success? Davis believes they owe a lot to their manager and their booking agent. He explains, “It doesn’t matter how talented you are as a musician, without good business contacts you go nowhere.”

And how has the international exposure affected the Dirty Dozen Band’s music? Says Davis:

“The contact with other musicians at festivals has inspired us all. It makes us want to expand what we’re doing.”

In the past the band played two or three funerals a week as well as several parades and other functions each month. Now their touring schedule has eliminated most of those gigs. While Davis regrets that loss, he does not see it as losing touch with the roots of the Dirty Dozen. The gigs at the Glass House remain essential to the growth of their music. Davis explains:

“It’s the one place where we can try a lot of things. Since the music is dance music and people at the Glass House aren’t afraid to really work it out. Its there where we see if the new stuff really works.”