*“Wow” is the word for “yes” in Wolof, the lingua franca in Senegal—one of many words from African indigenous languages that made it into the American linguistic mainstream during slavery.

Created by Gail Pellett and Stephan Van Dam

Why did you choose Senegal? we’ve been asked repeatedly. We’re here to dance we say. Only foreigners look puzzled. Senegalese break out into a knowing laughter. We explain. Because we are New Yorkers, we are following the musical triangle feed-back loop—West Africa, Cuba, New York, Dakar. Senegambia and other West African rhythms came with the enslaved on ships to Havana, New Orleans and the Eastern U.S. In late 19th Century Cuba those rhythms combined with classical melodies by Cervantes that by the 1940s evolved into Son and Mambo. Those rhythms and melodies traveled to New York City with Dizzy Gillespie’s help in the 50s nurturing Latin jazz and the mambo craze that looped back to Dakar in the 60s. As mambo enthusiasts who have also loved the driving rhythms and plaintive voices of Mbalax— by Youssou N’Dour, Cheikh Lo and Baaba Maal—we had heard about the legendary dance floors of Dakar. We are ready to salsa and mambo and learn the high-stepping movements of Mbalax with its complex rhythms and propulsive talking drums.

So here we are. Privileged travelers, guiltily expanding our carbon imprint. Only tonight we are alone in a beautiful club in Dakar. It’s 1 a.m. and we are the only people on the dance floor. We seem to have missed the schedule for live music around town, but the d.j. here is accommodating. Playing what is now considered old fashioned music for the older set – Africando, N’dor, Orchestra Baobab, Baba Maal.

We were told that the dance clubs would be packed. But it’s the wrong night of the week. Wednesday. The action is really Friday & Saturday nights. By then we’ll be in St Louis, 5 hours north of here. Our timing may be off but we have learned from taxi drivers, hotel workers, our guide and numerous others about new music that we are already downloading. More songs in Wolof that we wish we understood.

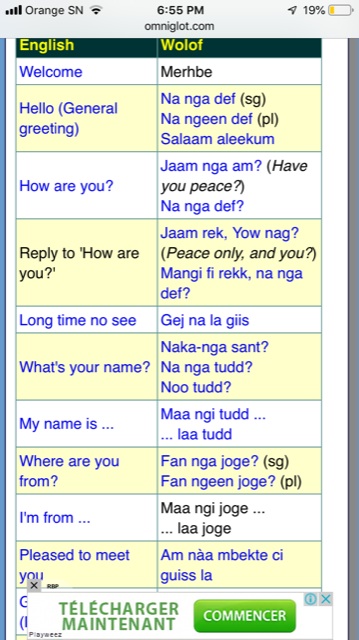

Did I say Wolof? Here we are in a country with 36 indigenous languages although one dominates—Wolof—the real national language. French, the former colonial language is still the official language. In city streets and in taxis, in the rural countryside, few people speak French. It is an administrative and business language which helps to keep a form of neo-colonialism alive. (More on that later).

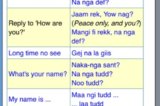

We are language challenged. We speak other colonial languages—English, Spanish and German—we say to disappointed faces. I am floundering in an effort to resuscitate my Canadian high school French while Stephan is tackling Wolof with gusto, eliciting more enthusiastic responses and giggles from everyone we meet. No snooty attitudes here about torturing languages. The bartender in our hotel insists on teaching us the correct pronunciation of Wolof numbers…stretching out the “neeyetttt” and “nyyyyaaar” for Number Two and Number Three. Or is it the other way around? Did we drink that many Flag beers?

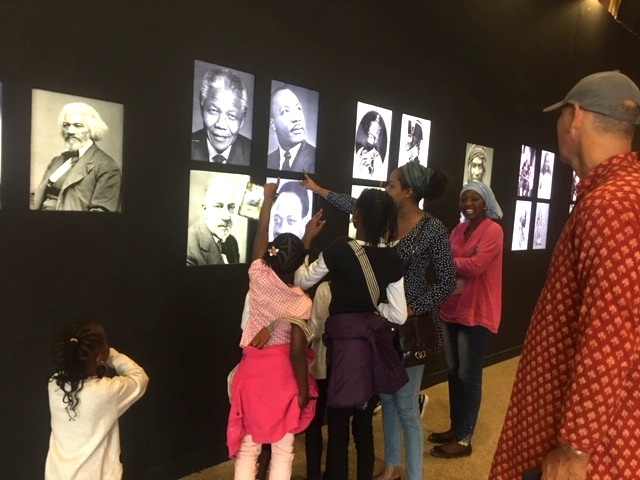

Another focus here is to look at art while learning about history and culture. Perhaps learn a bit about local politics and the economy. A ridiculous agenda for a two week visit without fluency in any local languages, but we have that kind of hubris and pluck. Conscious of our privilege we headed straight to the new Museum of Black Civilizations. Opened only in December of last year, with a prominent plaque out front declaring “China Aid” to make clear who paid for this grand building designed with a large dome at its center as a way to pay homage to a vernacular architectural style in much of Africa.

Repatriation or Reparations

This museum was constructed to be a repository for art that was “taken” or, more accurately, “stolen,” from the African continent by colonial masters and now resides in the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris or a dozen other major museums in Europe and the U.S. It doesn’t look like much has been returned yet. Repatriation, or shall we say “reparations,” is a controversial issue in Europe as it is in the U.S.

Why is this controversial? So much was plundered, taken, exploited, and disrupted on the African Continent (and the Americas & Asia) by European powers from the colonial era, including the most nefarious extraction of all—the Atlantic slave trade. Reparations and repatriation should not even be a question. The countries of Europe and the Americas owe a huge outstanding debt to the continent they carved up as well as to the descendants of former slaves who built their wealth. “Today,” according to the New York Times “the median white family (in the U.S.) has 41 times more wealth than the median African-American family. And things are getting worse.”

Upon entering the Museum of Black Civilizations we are thrilled to witness a gigantic metal sculpture of a baobab tree by the renowned artist, Edouard Duval-Carrié from Haiti. Called appropriately The Tree of Humanity. An acknowledgement of the centrality of the baobab tree to Senegal and much of Africa. In a way it is a metaphor for the role of Africa on the planet.

Maps in the lobby reveal how our start as homo sapiens, our languages and cultures began on this continent and spread outward around the globe.

Africanité and Négritude

It’s significant that this museum was built in Dakar since Senegal’s first president, the poet, Léopold Sédar Senghor, was a leader in the movement to define Africanité and negritude in the 1960s following the independence of so many former African colonies of France and Britain. Many intellectuals, writers and artists engaged in a passionate debate about negritude which Senghor defined as “a group of values common to the oldest inhabitants of Africa.” He walked his talk by committing funding for art museums and schools in Dakar.

I don’t think we can understand much about contemporary Senegalese or Sub-Saharan African culture without knowing more about the Négritude movement. Aimée Césaire, the Martinique writer, coined the term in 1934, and made a famous speech about Négritude at a 1987 international conference in Miami:

“Négritude is a necessary revolt against the European feeling of superiority,” he began. “Négritude is the result of an active attitude of the mind on the offensive. It is a somersault, a somersault of dignity. It is a refusal, and I mean a refusal of oppression. It is a struggle, that is to say, a struggle against inequality. It is also a revolt. … a form of revolt, mainly against the global cultural system as it had been constituted during the last several centuries, a system characterized by a certain number of prejudices, of assumptions which generate a very strict hierarchy. In other words, Négritude has been a revolt against what I shall call European reductionism…as Léopold Sédar Senghor would say, by reducing the concept of universality to its own dimensions; in other words, through its own categories…”

Here is a reference to the whole speech.

A contemporary dialogue about négritude ideas of Senghor vs. Wole Soyinka can be viewed in Manthia Diawara’s 2015 documentary.

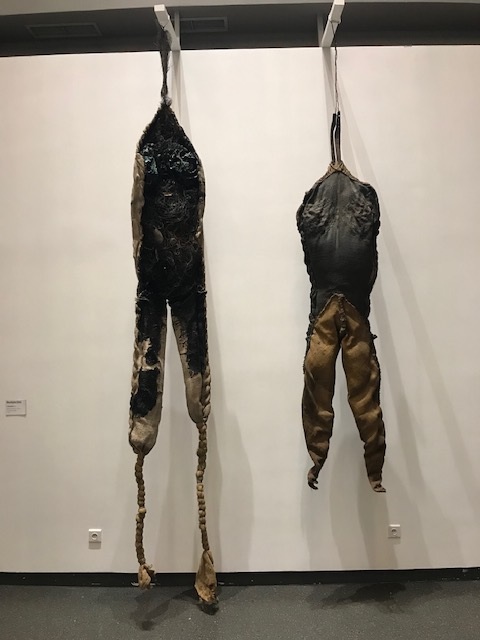

Meanwhile, at the Museum of Black Civilizations, a contemporary exhibit of plastic arts gathers work from the African diaspora provoking more reflection on the Négritude movement that celebrated the diaspora, and encouraged exploration of self and identity, along with ideas of home, home-going and belonging.

A gigantic sculptural wall hanging made of fabric scraps and found materials by Nigerian artist, Olanrewaju Tejuoso, recalls the impetus of Ghanaian artist, El Anatsui’s stitching of liquor wrappers and bottle caps to form hypnotic patterns in enormous flowing fabrics. (We had seen a powerful retrospective of El Anatsui’s work in Munich before heading to Dakar). By repurposing our everyday detritus, both artists are challenging us to think about our own responsibilities on this fragile planet, that is our home. And that creativity might help solve part of our crisis.

Another exhibition hall displays the history of Islam through exquisite renderings of Arabic script from the Koran and images of Bamba, the founder of Senegal’s most powerful Islamic brotherhood, the Mourides. Although there are several other significant brotherhoods here, Bamba’s image is ubiquitous everywhere we go.

We were ill-prepared for the dominance of Islam in Senegal. We knew a little about the Mourides, but the failure of our education about this continent keeps smacking us in the face. We are ashamed of our ignorance as we begin studying about the Kingdoms that predated Islam’s slow drip from the Berber traders descending from the north.

We have so many questions.

There is a theory that these pacifist Sufi branches of Islam may explain why Senegal is one of the rare countries on the continent with a series of peaceful democratic transitions of political leadership.

Our homework is cut out for us. We had not realized that some of the songs we have listened to by N’Dour and Baaba Maal and others address Senegalese history, independence and spiritual life. Cherif, our guide, who prays 5 times a day, explains that the hot new singer, Wally Sec, is preaching moral values for young people in some of his songs. Islam and the popular culture of everyday life have intertwined, he says.

Although few men or women seem to drink alcohol, the music and dancing are celebratory. Sufism? In the late 70s I produced a piece for NPR about the Whirling Dervishes visiting NYC. They are the ecstatic expression of Sufism. Perhaps Mbalax is the Senegalese version of that joyful ecstasy. Just wondering.

We are curious about how women relate to this religion, since only men seem to be entering the mosque and praying on the streets. Somehow, this question is never answered.

We also visit Ourrouss, the private gallery of Ms. Seynabou Guéye in Les Almadies, a toney neighborhood in Northern Dakar. Guéye’s collection features traditional masks and objects from Mali, the Gambia, Burkina Faso, Congo, and Guinea. Why not from Senegal? We learn that much of the traditional art from indigenous and animist societies was suppressed by the powerful Islamist traditions that have occupied religious space here since the 12th Century.

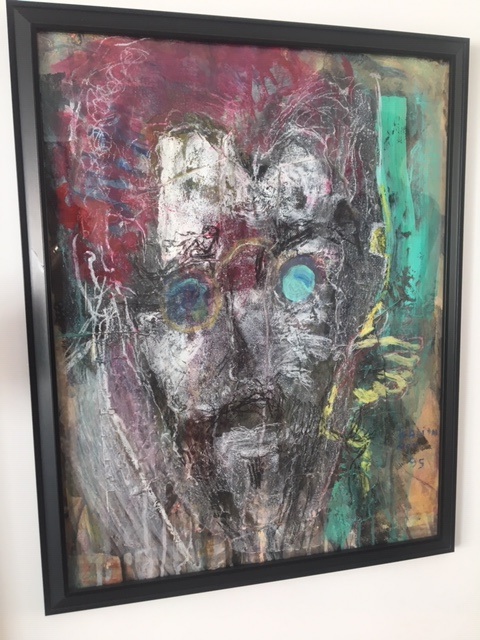

At Ourrouss we see a contemporary exhibit curated by Bara Diokhane, attorney, artist and collector who bounces between New York and Dakar.

The show includes work by Issa Saamb (1945-2017), painter, sculptor, performing artist, writer, and co-founder (along with playwrights and filmmakers) of the Labortoire Agit’Art Movement in the 1970s in Dakar. All part of a contemporary art explosion along with the famous “Art School of Dakar” (from 60s to 80s) inspired and supported by President Senghor’s commitment to cultural funding and the new Negritude and Africanité movement.

Searching out contemporary local artists who emerged from the Agit’Art movement, we visited the Village des Artes on the outskirts of Dakar. Quonset huts were erected here for Chinese workers when the Chinese government built the huge new national soccer stadium back in the mid-80s. When the workers left, more than fifty artists moved in—sculptors, potters, painters, paper makers, and collagists.

One artist, Amadou Dieng, immediately handed us his Manifesto:

“I do not make what is called “AFRICAN paintings.”; I am an AFRICAN who paints.”

Can a man teach another man how to caress a woman? I am self-taught; I therefore spontaneously started to paint. When I am in front of a canvas, All notion of preconception leaves me, And only one desire remains, To start with chaos, and end with order…” his manifesto begins.

We appreciate why Dieng won’t enter exhibitions where he is being defined as an “African” or “Black” artist because our beloved friend, painter & collagist, Paul Gardère, fought this battle his entire career. Originally from Haiti, trained at Yale, influenced by vodou symbology and the history of Western Art, obsessed with the historical implications of the Black Atlantic, his creations have deepened our aesthetic and intellectual life. We hope one day his work will be included in the Museum of Black Civilizations.

Sous-verre

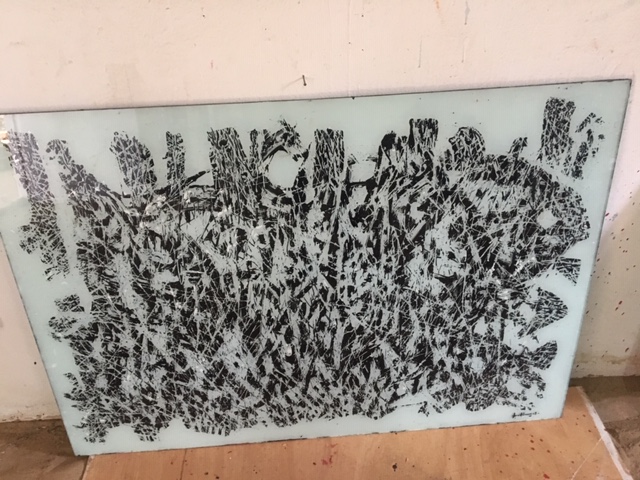

In Dieng’s studio we admire his abstract renderings using the sous-verre technique. This art form—painting on the back of glass— seems mostly to thrive as popular tourist art around Dakar.

We are delighted to discover that this art technique and even some of its patterned form has influenced the paintings of our friend, Gabriele Racke, in East Hampton, NY. Gabriele spent several years in West Africa in the late 70s, and creates whimsical paintings using the sous-verre technique.

The only women artists we discover at the Village des Artistes are two sisters, papermakers and art book makers. Fatou and Aicha. We chat them up as Fatou speaks English and we buy a lovely artisan book with paper made from the bissop (hibiscus) flower to show the paper artisans in San Agustin Etla, Oaxaca, a Zapotec village where we live half the year. Both here and there, the paper creators use flowers, leaves, bark, and seeds to color and texturize their papers.

Outdoor sculpture here in the Village des Artistes is buried in the fine sand and dirt that blows from the Sahara or the Sahel.

Landscape of Sand

We have overpowering reactions to the landscape of Dakar. I don’t know what I thought the landscape of Senegal would be. Somehow being “Sub-Saharan Africa;” meant in my mind’s eye, greenery. Bush. Maybe a little tropical jungle. I wasn’t prepared for it to be desert, barren, sand and more sand. Wind and sand and grit. We are now researching and contemplating the difference between desert, sahel and savanne.

Choking Pollution & Face Masks

On a Monday morning driving from our ocean’s edge hotel to downtown Dakar we are prisoners of choking traffic, exhaust fumes mixed with those powerful Saharan winds slapping us with sand blended with fine dust. There also seems to be a cement plant close to the west side highway that adds to the unbreathable mix. We are wearing face masks even though we are sea side. Everyone says the winds have grown worse in recent years. Climate change. It is the pollution mixed with the Sahara that slows us down. We will miss visiting other art venues like the Material Raw art space as well as the special new museum of Senegal’s most famous artist, the sculptor, Ousmane Sow, who died in 2016.

Marchands Ambulants – Itinerant Vendors

Walking some of the streets of downtown Dakar we are confronted by the congestion—armies of young men migrating to the city from the countryside to join the legions of unemployed youth in the cities—creating an “informal” market of marchands ambulants or itinerant merchants on side-walks and streets. Regular shops and stores are sometimes obliterated by their stalls and physical presence. Sixty percent of Senegal’s population is under 25 and most are unemployed or underemployed in the formal economy.

Marchands ambulants carry their wares on their arms—cell phone covers, phone cards, clocks & watches, textiles, belts, tourist trinkets. Mostly products from China. We learn from a local store owner that when the government tried to “clear” the marchands ambulants from the streets, the reaction was immediate and violent. We recognize this issue from Oaxaca city, in Mexico. The presence of walking vendors reveals the lack or failure of economic opportunity. In Senegal we sense it is a combustive brew waiting to explode.

On the route from the airport to the hotel our driver maneuvered through a phalanx of middle-aged women marchands ambulants selling mostly peanuts, cashews and baobab candies. Peanuts! Delicious peanuts! It was the enslaved from this coast who introduced peanut growing, along with rice growing and irrigation to the plantation owners of the American southeast.

Then we learn it was the French colonial effort to turn peanut growing into a singular cash-crop enterprise that led eventually to desertification and starvation as farmers gave up ancient sustainable mixed crop farming.

We are learning so much. But we know nothing!

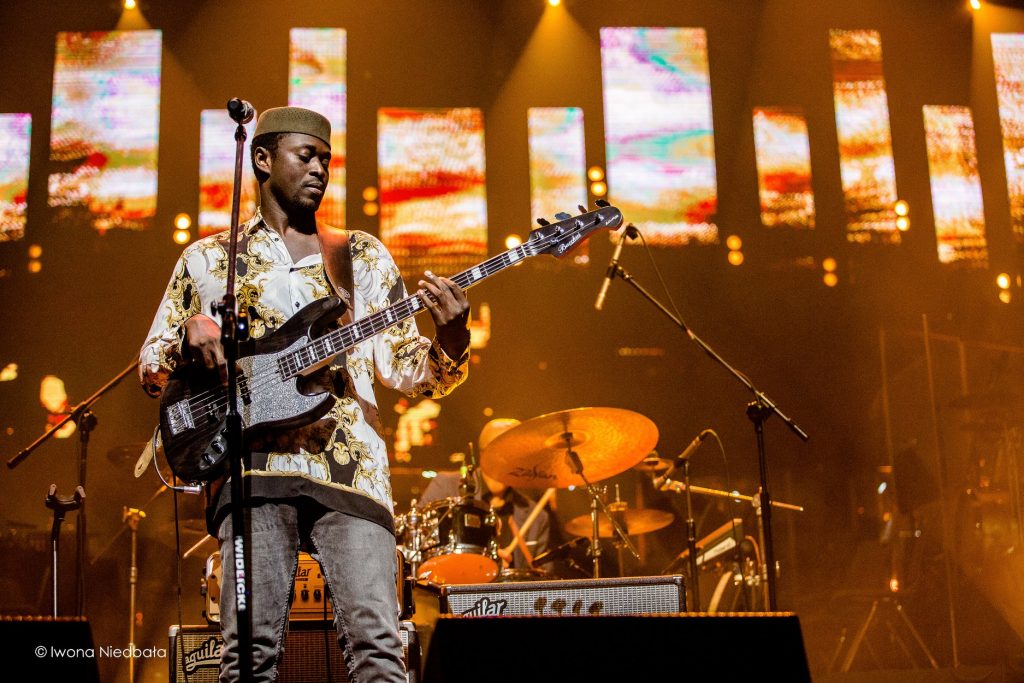

During a traditional Senegalese lunch of yassa poulet (Sweet & sour sauce of onion and spices on chicken) at the French Cultural Institute downtown we meet Alune Wade, the hot new jazz bassist and vocalist, buy his CD and get his signature.

Check out his music here.

Gorée Island

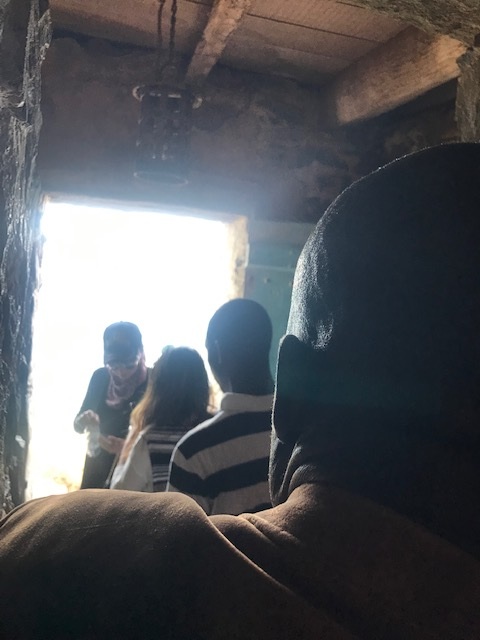

Our trip to the historic Ile de Gorée, a UNESCO site preserving the slave dungeons used for transferring shackled Senegambians to ships was a welcome relief from the pollution of Dakar. Ironic. We had expected this trek to be defined by profound emotions as we contemplated the compounding evils of the Atlantic Slave trade—disruption on both sides of the Atlantic, loss, pain, violence and death, with devastating consequences that continue unfolding in today’s United States and elsewhere. Yet here we are enjoying Gorée’s clear air and bougainvillea smothered 19th century buildings connected by sand covered pathways. No cars on the island! No pollution. Instead, fresh breezes, gentle beauty. Strange and deeply troubling juxtapositions. History and landscape.

We have mixed feelings about visiting the holding dungeons and passageway where enslaved men, women and children were taken to ships. Too many tourists and lines of lively school kids complicate and distance our emotions. We must find our own time to reflect on the horrors and consequences of what went on here.

Outside, sellers of tourist art and trinkets are hustling. We are reminded that no matter how horrible the history here, today’s populace must survive.

My name Fatou. Fatou, ok? Remember me. My name is Mariama. Come. My shop. Mariama. I amYvette. I have good shop. Come my shop. Yvette. My name Yvette.

The famed Dakar market women are assertive, relentless and, yes, aggressive. They were already on the boat when we crossed to Gorée introducing themselves to make sure we would remember their names and search for their market stalls on the island. They are pushing peanuts & cashews, Baobab candies, bracelets, tie-died fabric dresses and pants. When we finally reach their stalls they entangle Stephan because he’s a softer touch. One told him he should get a Senegalese wife who would like to shop!

Migration & its Consequences

On Gorée, it is contemporary reality that stops us in our emotional tracks. Pierces our hearts. A current photo exhibit includes a color shot of a young man on a bike balancing an impossible load– symbolising the informal market.

This image confronts us with why so many men (mostly) risk their lives to migrate to Europe. In fatally inadequate boats. The following black and white photos reveal a body on a beach, covered, accompanied by a companion mourning.

We can fill in the back-story. We have heard and seen the news of the thousands who lose their lives crossing the Mediterranean. We have read about the abuse and exploitation migrants experience along the way. It is this exhibit that forces us to reflect. On the devastation of the slave trade both on the African continent and in the Americas, then years of colonialism and the economic consequences today.

We learn that by 2015 some 10% of the refugees washing ashore in Italy were from Senegal. They are coming mostly from the interior of the country where poverty levels and an exploding youthful population make survival precarious. In their desolate villages the only income they see is from the remittances sent back from those who successfully made it to Europe. Their only dream—reaching Europe. Yes, we have been doing some research. We must try to understand WHERE WE ARE!

Our skulls are already cracking. And our hearts are bursting.

The Sahel & the Baobab

The five hour drive from Dakar to St Louis, the former capital of Colonial French West Africa, is a deep plunge into the landscape of the Sahel. Derived from Arabic, Sahel is the buffer zone between the arid sands of the Sahara and the more humid Savannah further south. We are at the end of the long, long dry season, so to me this feels like it might be the Sahara. But then…trees and bush.

The evocative Baobab tree with its plump trunk and parched and crinkled explosion of barren branches at the top becomes our obsession. The-upside-down tree some call it. Haunting. Beautiful. We try to imagine what it looks like in the rain season to come. With leaves and fruit. Yes, the baobab fruit, leaves and bark are all said to contain a pharmacy of healthful remedies. We have also heard that in parts of Africa the Baobab is dying.

We are grabbing photos out of the dry warm air flowing in the car windows. Here and there bushes of another kind. Acacia trees much larger than we’ve ever seen before.

We expect camels but instead we see frisky goats and scrawny cattle. Cebu says Cherif who accompanies us to St Louis. Rural agricultural settlements hide behind cement brick walls. Mosques. Buses piled high with baggage and the occasional goat.

And always tall, erect, graceful mostly slender bodies moving through the landscape purposeful but unrushed. Stephan keeps pointing to the ram-rod straight, yet elegantly easy posture of the Senegalese, especially men. Since he is tall, he wonders how they manage it. As he looks at them, he stands up straighter.

The perfectly paved two lane road to St Louis is the major truck route from the grand Senegal River in the north and its accompanying wetlands, supplying rice and vegetables for the Dakar market. And of course, fish, a staple of the diet. All must be transported down this road. We pass through small cities and towns. Thiès. Tivaouane. Méckhé. Kébémèr, Louga.

Lunch on the road. Maafe: The peanut/tomato sauce stew of beef and vegetables.

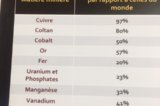

China in Senegal

We also pass the vast caravan of gigantic trucks transporting enormous pipes the Chinese are installing to bring water from the Senegal River to Dakar. (More than 250 kilometers). We are reminded that many deals have been struck between the Chinese and Senegal’s government that may have consequences down the road.

We are re-reading Howard French’s China’s Second Continent. One of the 15 countries he visits in Africa, is Senegal. The subtitle of the book is important here: How a Million Migrants are Building a New Empire in Africa.

One point French makes is that the Lebanese traders and business people who used to dominate Dakar’s shops have been pushed out and replaced by the Chinese. We witnessed some of that in downtown Dakar, but have no idea whether that is a good or bad thing. Or more of the same. We also saw all the Chinese products that the itinerant and stall owning marketers are selling. But China’s overall scheme here is more complex. They must feed themselves and find places for the restless and frustrated of China to go. And the Chinese government will expect full support from Senegal’s leadership for their positions at the U.N. and other international institutions in return for generous loans for infrastructure…or museums.

The irony here, of course, is that migrants from China can come to settle and try out their entrepreneurial skills here while local young men from the countryside, without income or hopes for the future are leaving in significant numbers on perilous journeys northward, eventually crossing the Mediterranean to uncertain outcomes. We think of all this while traveling the road to St Louis and looking out over the vast seemingly barren landscape. Knowing it is not barren. Only windy, parched hard at the end of the long dry season.

We still know nothing!

We are reminded of Youssou N’Dor’s most recent album, History, whereby one song (in English) insists:

“This one’s for my father and his father; It’s about where we come from, not what we run from.”

Lunch with Cherif’s Family

While we had hired a guide, Cherif Ndiaye to help us navigate in Dakar where most taxi drivers speak only Wolof, we decided that for our week in St Louis we wanted to just drift on our own, and, despite all of our language limitations, to engage with locals. Communicating through a translator is too distancing for us.

St Louis, however, was Cherif’s hometown so he generously invited us for a meal with his extended family.

We met Cherif’s wife, daughter and sons, his sister-in-law, nieces and nephews and their children who all live in one compound.

We were delighted to see that some of those fantastic over-stuffed chairs being made and sold in town markets along the highway were happily ensconced here. A surprising aesthetic touch were the crocheted doilies! Just like in my British grandmother’s house in Vancouver, Canada.

We learned that families gather on the ground or floor, with one main dish and everyone eats out of that dish.

Aimée, Cherif’s wife, had made Senegal’s national dish – Thieboudienne – a one pot dish with three kinds of fish, vegetables and rice in a spicy tomato sauce. Everyone eats with their hands.

Communal Eating

Watching ten people squatting around a communal dish on a tablecloth covering the ground, eating with their hands from the same pot, provoked our thinking about how distanced and alienated Western eating culture has become. Individual plates, antiseptic metal instruments. Perhaps eating from the same dish with your hands creates a sense of shared survival and inter-dependency and encourages self-discipline!

Titi!

Cherif’s niece turns us onto Titi – and her songs, Mame Saliou and Guen Gui Deuk become our anthems for the rest of our journey. The latter is a plaintive, soulful song of lovers separated by migration. Long distance love. “You’re there, I’m here and I still love you…I love you. I believe in you…I’m not dreaming.”

St Louis, Fading Former Colonial Capital

Now a UNESCO site, the Isle de St Louis occupies a small island between a long sandy ocean side spit home to a bustling fishing village, and a mainland town where most St Louisians live and shop.

From the mid 1600s St Louis was the original colonial capital of French West Africa. It’s strategic position at the mouth of the grand Senegal River with its rich inland wetlands made it desirable to the Portuguese, the Dutch and the British. But the French prevailed, even if they were late comers. Egyptian, Greek and Arab philosophers and wanderers referred to the Senegal River before the French were even a concept.

St Louis lost its primary place when railroads were built from Bamako, Mali to Dakar to meet the new deep water ports. Dakar became the new capital of French West Africa at the dawn of the 20th Century. Since then St Louis’ colonial buildings have been crumbling. Today, renovated structures share the same block with the deteriorated and collapsed along its sand swept streets. Tourists come for the annual jazz and film festivals. Again, our timing was off, but we loved the sleepiness.

Sleepiness? After being woken early one morning at our St Louis hotel by the passionate call to prayer by a local imam, I wondered if Sam Cooke was in the house! In visits to Istanbul, Fez and parts of India, I had never heard such falsetto, potency and vibrancy in the singing voice of the Imam.

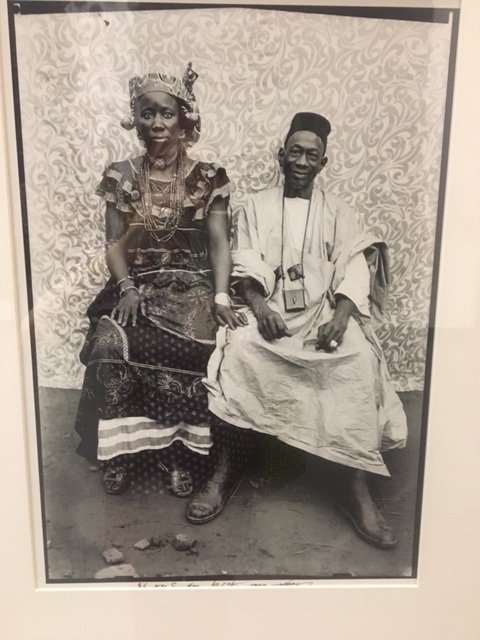

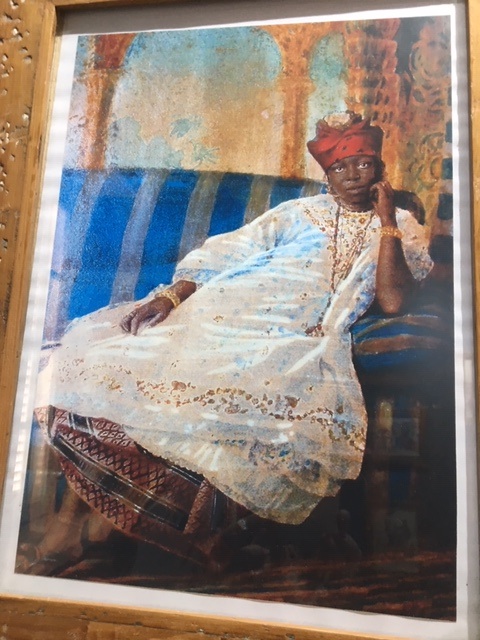

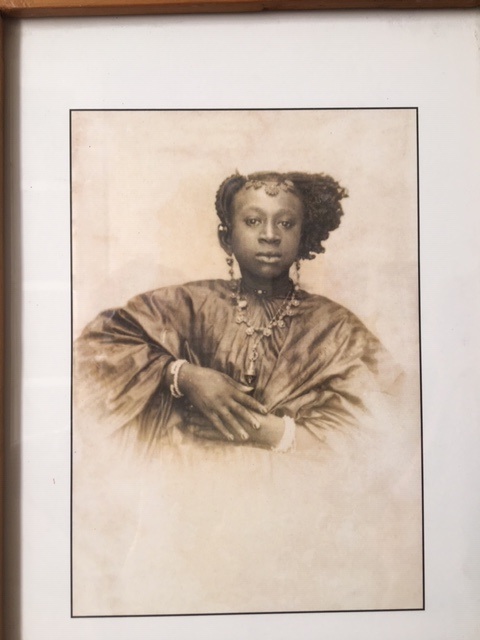

Les Signares

At an exquisite little Museum of Photography we learn about the Signares, African women who partnered with European men and their mixed race daughters. Not until the end of the 19th Century were French traders, officials and soldiers allowed to bring European women to Senegal. The ban was supposedly for sanitary reasons.

The Signares were essential cultural translators and economic negotiators for the trading of materials and acquiring of land and property. Many of them became powerful and wealthy, managing large properties, forming influential clubs and dressing elegantly. They played a role in the slave trade as well, some owning slaves for their own purposes, sometimes to prevent enslaved servants from being sold into the Atlantic slave trade. We learn that these women played a key role in the creation of a Creole class that continues to play a vital role in business and community life in today’s St Louis.

We set out to find the Hotel Louisiane, owned and operated by a female descendant of a signare. We read that the proprietor “pays homage to her foremothers” displaying photographs and objects from the signares of that time. Sadly, the hotel had closed.

Instead we discover the Hotel d’Maison Au Fil du Fleuve, a guest house conjured out of a derelict waterfront warehouse by the irrepressible Marie-Caroline Camara, a contemporary Creole. Her mother was from Normandy, her father was local Senegalese. She is generous in sharing her life and thoughts. We cannot resist photographing the stylish furnishings in her sandy courtyard.

Art on the Body: a Multinational story

We have seen so may gorgeous fabric prints parading around the streets in Dakar, on the road and here in St Louis, creating living moving bodies of art, that we want to know where these fabrics are made.

We discover a surprising story of globalization and appropriation. The Dutch colonists copied Indonesian designs and techniques of wax printing on fabric to evolve highly colorful, abstract or figurative cotton prints which mostly sold in West Africa where the women customers, merchants, and seamstresses would provide a feedback loop of ideas for color and design. Now the Chinese are copying the fabric designs to sell into this same market. So…you can see how global it gets.

It was then a wonderful discovery to find the tie-died fabrics made locally. Yande is the proprietor of this fabric and tailor shop.

In a St Louis crepe shop serving citron banane gingembre, (Lemon, banana, ginger crepes) Stephan cannot stop photographing the Bauhaus design including the furniture as well as the co-ordinated fabric of the Hostess’ hat that matched the furniture and pillows.

Then one day we discovered a local weaver working in an open space off of a side street. He is part of the workshop of Galerie Atelier TËSSS on the corner.

Maï Diop, has run the Gallery and Ateliers TËSSS, a Wolof word for textile, for over 15 years, trying to preserve a fragile heritage.

Originally from Southern France Mai had a career as a film set designer in Paris before heading for Senegal to change her life where she has married into the Diop family.

Our conversation cranks up as we share with her that we live part of the year in a textile region of Mexico—Oaxaca. She knows about Oaxaca and begins to share more about her textile research and work.

She explains that TËSSS was created to save a disappearing, traditional technique and style of weaving in Senegal, called “Mandjak.” She claims that Mandjak weaving “is the most highly perfected, preserving its original cultural tradition” from the Cape Verde Islands off the coast of Senegal as well as the mainland. Yet, due to economic conditions and changes, this art appears to be highly endangered here.

Examples of Manjak textile design

Patterning

Later at, L’Agneau Carnivore, an exquisite book shop also selling extraordinary pieces of traditional West African art we are provoked to think and learn about the significance of patterns and symbols throughout West African art. Perusing a book on the Kuba of the Congo we learn a little about the deep significance of these symbol systems.

Apparently, the specialized non-verbal language of abstract shapes created by indigenous craftspeople was carefully guarded from the queries of colonialists and even Western researchers. These shapes create a semiotics and the West remains largely ignorant of their meaning.

We think again about the exuberant patterns when we visit the ultra stylish shop of the brother-sister team, Riam and Joe Diaw. On the streets and here patterns are often juxtaposed in wild and surprising ways on a single piece of fabric or on a garment with several different fabric designs mashed together.

Conversations about neo-colonialism

The conversation with local customers and friends at the store quickly turns to the frustrations of Senegalese entrepreneurs. According to them, if you are French you can cut through the government bureaucracy in a couple of days to purchase property or get a loan for a business. Local Senegalese face months of paperwork and delays. It adds to the subservient feeling that local owners feel toward the French who dominate in banking, control the currency and own the only telecommunications system in Senegal among other entities.

Over croissants and coffee at our St Louis hotel, a French food scientist tells us that she is here to research why Senegalese women prefer to cook with imported rice rather than their home grown rice which is grown heavily in this region. It has become an economic paradox and one of the slippery slopes of colonialism—building desire for foreign import goods. We are pleased to discover the hotel dining room is using local rice. The next day at the same breakfast table we met a group of Korean businessmen who are in the rice business—clearly on a mission—claiming their rice is “stickier.”

A Plastic Catastrophe

While the streets of St Louis had their own beauty and elegance, the minute we reached the edge of the island or walked the bridge to the fishing village on the sand spit, we were confronted by acres of garbage pollution, mostly plastic. We had seen it along the highway on the trip from Dakar. Plastic detritus everywhere. The morning we took a taxi to the beach from St Louis, we quickly turned away from what were once beautiful expansive white sand ocean beaches because of the volume of garbage, again mostly plastic, everywhere. Plastic bags in the desert, the Sahel, the Savanne, all over the beaches. What have we done?

It provoked our questions about the mosques and the brotherhoods; about government – both municipal and federal; about the French, Belgian and Chinese investors who are so involved in Senegal. Who is responsible for this “catastrophe” of pollution, as one of our drivers put it?

We mention Islam, because devout men and boys wash themselves five times a day before their prayers. Why is the environment not included in that cleansing? With so many unemployed, so many young boys involved in Koranic schools whose tradition is to send their youngest flock out to beg in the streets, why isn’t one of the major projects about cleaning up communities? And where is the government on this issue?

We realize with short reflection how “alienated” we are from our own refuse at home. Whether we rely on municipal garbage trucks or take our own refuse to the recycling center, we then wash our hands of it. Where does it go? Is it sold or dumped in poor communities in the South? China used to buy U.S. garbage. No more. And we in North America create tons more plastic garbage per person because of our more affluent and materialistic lives. In Senegal, there is no escaping or hiding from this global dilemma.

Titi & leaving St Louis

On our drive through the evocative Sahel heading to a birding park south of Dakar we reflect on all we have been learning while listening to the heart-aching songs of our latest idol, Titi. Her crooning about long distance love affairs, of which there must be so many in a country where young men leave to pursue opportunities for survival in Europe, digs deep into our souls while juicing us up with all those talking drums.

In one of our favorites, Guen Gui Duek, she also sings, “They can think whatever they want about me. Let them say whatever they want about me. It’s to me to choose who to love and I chose you.” We are forced to question the pressures upon women to marry, within their brotherhood? village? ethnic group? class? “I’m afraid I’ll wake up and the dream will be over.”

We’re also hooked on N’Dour’s new album, History, and the newly discovered Alune Wade’s album that evokes landscape and culture with minor scales.

Next: Birds!

We ended our Senegal stay with a couple of days at an eco-lodge south of Dakar. A garden oasis surrounded by birds, before returning to a broken and troubled country, the U.S.

Stephan’s bird list: Guinea pidgeon, Pigeon gris, Souimanga eclatant, Souimanga Superb, Souimanga a longue queue, Tourterelle du Cap, Tourterelle Maillée, Tourterelle pleureuse, Purple Galinule, Gonolek de Barberie, Milan parasite, Le corbeau pie, Calao a bec noir, Calao a bec rouge, Agrobate roux, Cordón Blue, Tisserine Gendarme, Travailleur a bec rouge, Pelican Gris, Pelican Blanc, Hirondelle de Deméter, Vanneau epperonné.

Send these 2 around the world – I love to hear about their travels & discoveries!

Wow is the only word. So impressive. So delicious. Kudos.

This is a wonderful, analytic and thoughtful travelogue that immerses us into music and art in Senegal. A great read and lovely photos well chosen. Thank you!

Thank you, Ingrid, Jeanie & Vera for taking time to read and comment.

Wonderful! Superb! Just fascinating. It certainly brightened up my subway ride on this gray rainy day. You both struck the right tone- of politics and art, pleasure and knowledge. the sense of pleasure was palpable. I learned a lot. Travelogue is your metier! But where is the map through the Sahel? I’m waiting for it!

Listening to Titi la lionne while seeing your beautiful photographs, expanding horizons – thank you!

That was our hope – that you would play the music while reading & looking…see you soon, Stefan. Can you send us dates again for your events.

Thanks for your enthusiasm, Nanette!

Please publish this somewhere. It’s the type of travel writing (and photography) that breaks through the crap. Loved it all — and totally jealous that you did not invite me along–though three for dancing is a bit awkward. xxx

Enjoyed your in-depth record of your encounter with Senegal and the many questions it holds for us! And every picture tells a thousand words!

Impecable article!! It felt as if I was there with the two of you!!! You are a National Treasure!!! Say It Loud!!!

This article and the photos are out of this world. Or, rather, they are so deeply in this world, that they took me out of mine. Thank you for bringing these experiences to me.

Thank you for your thoughts on this, Nanette. We have wrestled with the map issue (of course) and haven’t found the right one that we have the rights to…but it’s still a work in progress before this gets published elsewhere.

So glad you were able to enjoy this, Claudio. Thanks for taking time to read and respond!

Your curiosity and courage make you such remarkable travellers. Amazing as always.

Another unforgettable deep dive cultural/political/artistic journey with you and Stephan,

We come away from considering all you’ve brought back wanting more.

Great balance between your investigative chops and your traveler’s delight.

xMirra

Superb! Magnifique! A truly wonderful journey that brings sadness, hope and tears. BRAVO mes amies

Thank you, Bob, for taking all that time to read and respond. I hope you saw the bird list at the end????

Thank you, Mirra, for your generosity of time and thought on this L-O-O-N-G piece! xoxGail

Elsa, dear friend, thank you for taking time to read and comment. Hope to see you soon!!! xoxg

A very insightful narrative by seasoned travellers like you and Stephan….brings back pleasant memories of our several visits over the years. Senegal has always occupied a unique position in the socio-cultural and political history of Africa, and your piece managed to capture its essence. Bravo!

Felicidades! it´s a great blog. I loved the texts and the fotos.

Gail & Stephan –

I’m blown away by the art – and by your photos of the art. I’m also blown away by your deep thirst for understanding. Continuing to read and study during your visit, all the while traveling, looking, talking, listening – and dancing.

Xxsherry