This article originally appeared on Medium.com on September 6, 2018

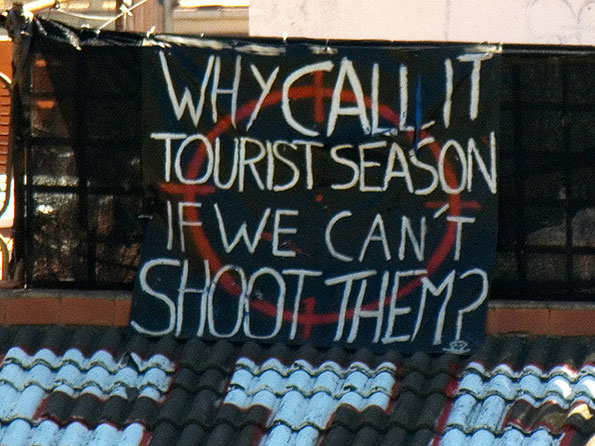

The graffiti screams and shocks. A human silhouette sprayed in black on a wall with a red target blasted on its head and the words “Why call it the tourist season if we can’t shoot them?” This is Barcelona where militants have slashed tires and set fire to tourist buses; where hotels have been paint-bombed and demonstrators filled the streets in a growing resistance movement to mass tourism that many locals see as destroying their city. An article in Euro News 2017 states: “The problem has a name: “terramotourism” or tourism earthquake.”

Opposition is ratcheting up in major tourist destinations around the world—not only in the major cities of Europe. From the closing of heavily trafficked beaches in Bali while tons of tourist garbage is cleared to the banning of visitors from a popular tropical island in Thailand and the UNESCO pronouncements about Venice. The city is dying under the weight of mass tourism.

Venice should be a warning. Once a rich and boisterous financial and trading capital, Venice has witnessed it’s local population shrink to about 50,000—a third of it’s population in the 1950s—while 20 million tourists annually invade from cruise ships and jumbo jets. Shops and services necessary to support a domestic life have all but disappeared.

Tourism can be invasive, exploitative, distorting, and destructive. Fodor’s 2018 travel guide has recommended tourists stop visiting the Galapagos Islands and the Great Wall of China because of environmental degradation from tourism. Besides Venice, they advise to avoid Amsterdam and Phang Nga Park in Thailand.

Mass tourism not only has led to the deterioration of the natural and built worlds but guzzles local natural resources, especially water. Angkor Wat in Siem Reap, Cambodia, is sinking from the overbuilding of hotels that are draining the water table. The temples themselves are disintegrating from too many tourists walking over them and touching everything.

Allison Jane Smith in her provocative article, “The Next Trend in Travel…Don’t.” (published on medium.com earlier this year) quotes a Balinese community activist, Viebeke Lengkong. “It is a question of what kind of services we can actually provide for millions of tourists. Bali is in the middle of a water crisis. Bali is drying up.” This statement could be made for other world tourism hotspots—like Mexico—where a recent report indicated that most of Mexico’s water reservoirs have sunk below the half way mark due to global warming and drought—a vulnerable situation for sustaining the local population. Yet tourist resorts keep popping up on the Mayan Riviera and the Pacific coast.

Venice and Barcelona are not the only places where tourism has overwhelmed local populations. In Tanzania thousands of indigenous residents in rural communities have been moved out and hundreds of homes burnt to make way for bigger game reserves. Jonathan Watts reports in The Guardian (May, 2018) that the Tanzanian government is placing the needs of foreign safari companies— specifically, Thomson Safaris, based in the U.S., and Otterlo Business Corp, based in the United Arab Emirates—above those of Maasai herding communities “as environmental tensions grow on the fringes of the Serengeti national park…although carried out in the name of conservation, these measures enable wealthy foreigners to watch or hunt lions, zebra, wildebeest, giraffes and other wildlife, while the authorities exclude local people and their cattle from watering holes and arable land…”

On Cambodia’s coast, as on tropical coasts elsewhere, local inhabitants—usually traditional fishing communities—have been forcibly moved out to make way for yet more resort hotels. One small fishing town on the Baja, California coast of Mexico successfully organized against a mega American company that wanted to push out local fishermen to build an “eco resort”—on a coast saturated with resorts—that would have endangered already stressed local water supplies. Now, that partially built project lies in ruins and the fishing community has their coastal access back. A documentary film traces that remarkable two and a half year battle. (Patromonio).

Environmentalists remind us that all our long distance jet travel, and increasing numbers and size of cruise ships along with cars, buses and air conditioned hotels and resorts are contributing an enormous carbon footprint. On top of overcrowded World Heritage sites—including the inner historic city of Dubrovnik—as well as pressures on infrastructure and public services comes the disrespect for local culture when luxury international hotel chains replace local facilities so that every accommodation worldwide looks and feels the same. The danger everywhere is the loss of cultural authenticity as the same branded hotel and store chains appear in San Francisco or Shanghai. The flattening of cultural specificity is not just boring, it destroys pride, identity, complexity and souls.

And there are deeper social problems. Child sex trafficking has exploded in tourist meccas like Cambodia. In addition, orphanage tourism has encouraged poor parents to send their children to facilities where tourists can bring gifts and play with the children.

In many of the top tourist cities from Vancouver to New Orleans, Barcelona to Berlin there have been populist movements to regulate AirBnB rentals as they force out locals by raising rents and disrupting communities.

This is not upper class snobbery toward cheap travel enthusiasts. We, of the traveling classes—from backpackers to family reunion excursionists, from business tourists to cruise ship masses, luxury safari goers or digital nomads—we, all of us, are guilty. And while the U.N., governments, business owners and even us tourists will argue that travel can lead to peace and mutual understanding, the solutions to the devastation of environments, cultures, communities and historic sites, can only be tackled politically by governments and through a radical transformation of consciousness globally.

That project will be monumental because the lure of tourist dollars is corrupting. The U.N. World Travel & Tourism Council’s 2018 report reveals that travel and tourism is one of the largest global industries, generating 8.2 trillion U.S. dollars of revenues world wide in 2017, creating some 313 million jobs or one in ten on the planet. The growth rate of the industry has outpaced the growth rate of the global economy. Now there are more than a billion tourist trips crossing borders annually. The United Nations projects that number will be almost double by 2030 as the new Chinese and Indian middle classes hit the road.

Governments welcome tourism as an engine of economic development. Tourism is the top single revenue source for countries from France to Thailand. New York City’s five boroughs are home to a population of roughly 8 million, but city boosterism has led to more than 62 million annual tourists who crowd mostly Manhattan sites, cultural institutions, choke roads with Ubers and taxis, overwhelm sidewalks and the crumbling subway system. But the 67 billion dollars visitors spend supports middle-class jobs even for those without college educations. After 45 years of living in Manhattan, last year my husband and I moved out. One reason, overcrowding from tourism.

Despite the monumental scale of the industry, and its environmental, infrastructure and resource stress, it is seldom treated critically in the press. Travel pages of our shrinking newspapers and magazines cannot be relied upon to raise questions. Again money talks. Advertising revenues for the tourist industry are too sweet. Most travel writers get paid to visit destinations, hotels and restaurants by the industry itself. Recently, a travel editor at the New York Times, one of the few newspapers that doesn’t allow industry supported writing, wrote a glowing report on cruise ship travel pooh-poohing those who have raised critical questions. This is a disservice to the planet…and consequently, the human project.

Elizbeth Becker who has written extensively and critically about the travel and tourism industry worries that the industry “is now so big that it will inevitably be part of conversations about climate change, pollution and migration.”

How did we get here?

Humans have been traveling since we stood up on two feet—the wandering of the human population from Africa across the globe being one of the first grand migrations. Indigenous nomads moved their communities and kingdoms for centuries. And since the Greeks began recording their history we have been reading about the journeys of Odysseus from Homer; or Heroditus’ travels to collect first hand accounts of conflicts in his world radius. Xuanzang, a Buddhist monk from Central China, made a 17 year pilgrimage from Central China to India in the seventh Century and wrote about it. Traveling merchants like Marco Polo ventured further in the opposite direction. Explorers from Asia and the South Pacific followed the currents, winds and stars across half the globe. The Vikings were brave and curious sailors, too. There were religious pilgrims. Crusaders. Knights errant—even if their romantic wanderings were only imagined.

Travel motivated by the hunger for gold, spices and the color red built wealthy cities in Europe. Whether it was the search for a route to Asia, or beaver pelts and sugar, explorers and conquistadors began penetrating the Americas.

The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed adventurers and scientists prowling New World habitats to study the flora and fauna while others in their party were crushing local human cultures, then consuming and marketing the natural resources. The dialectic of travel.

During that great period of imperialism, travel followed empire builders: soldiers, administrators, businessmen, wives, and missionaries rode the seas to the colonies. India, Ceylon, Burma, Australia, New Zealand, Canada. It is no secret that these travelers on the imperial agenda were mostly white.

Migrant settlers and laborers “from the old world” followed in the conquerors footsteps. That massive movement included my grandparents who left a bucolic agricultural village in England after WWI with six kids to venture to the harsh and desolate landscape of the Canadian prairie to farm the rocks. It was a push, pull phenomenon—imperialist in its design—but adventurous, brave travel nevertheless. They remained ignorant that their travel adventure was at the cost of native populations who once roamed widely through a vast swath of the continent, but were now confined to reservations, their livelihood destroyed. More contradictions.

While aristocrats in England sallied off on the Grand Tour of Europe, or sought the exoticism of a newly colonized Arab world, slave traders plied the triangle route trafficking Africans, sugar and rum.

Travel has always produced radically different stories. While privileged travelers on one side of the world crossed borders in pursuit of cultural enlightenment and opportunities, in the United States runaway slaves traveled by night through swamps and ominous forests—facing down unimaginable dangers—to reach freedom and safety often crossing the border into Canada.

Much ink has been spilled for more than a century in an effort to distinguish the traveler from the tourist. Some argue that the traveler takes time, explores the history and language of their destination, and desires a transformative experience. Historically travelers have always despised the ignorant, arrogant or bad-acting tourist. The tourist, according to some, is rushed, only interested in proving their presence at historic sites (hence all those photos and now selfies). The tourist, this argument goes, generally fears the unknown. Perhaps the element of fear is the distinguishing characteristic. Not simply desire.

Camus once argued that all travel involves fear. He saw true travel not as pleasure but as “spiritual testing” that brings us “back to ourselves.”

Jump cut to the 21st Century and the explosion of mass tourism. While cruise ships carrying 3,000 partying passengers ply the Mediterranean—sitting atop the largest septic tanks of human waste on the globe—more than 8,000 migrants and refugees fleeing war, poverty, and climate change have drowned in leaky boats or disappeared in that same sea crossing in search of safety and freedom in Europe. More than 85 million refugees are on the move today or are living in camps outside of their countries. Yes, they are travelers, too. The life threatening travel of refugees has historically disturbed the rarefied notion of travel promising some form of salvation, discovery or transformation.

The travel and tourism industry changed throughout the last century. Travel for escape, relaxation, recreation, hedonism and consumerism gradually replaced travel motivated by curiosity, understanding or enlightenment.

In 1958, I was part of a student group leaving Victoria B.C. on the west coast of Canada for a teacher led tour of Europe. We represented the early stages of mass tourism since we numbered well over one hundred and were about to invade historic buildings, sites and museums in eight countries in less than four weeks. After a train ride across Canada, we flew from Montreal on a prop plane that had to refuel in Gander, Newfoundland, then again in Shannon, Ireland before landing in London. That same year the first jet plane flew from New York to Brussels without refueling. Mass tourism was now officially launched.

Some would argue it began much earlier. Travelers in the late 19th C—mostly British aristocrats—complained about the growing middle class tourist onslaught and their uneducated behavior on the European Grand Tour. Those increasing numbers were expedited by bigger and faster ships.

During the 1960s and 70s, lower airfares and more relaxed passport regulations in Europe meant that tourists from the U.S. were now doing the continental tour in three weeks. Middle class Americans became the biggest tourist class in the world. In the thirty years from 1950 to 1980 global tourists crossing borders multiplied ten times. Larger jets going longer distances with lower cost fuel transported curiosity seekers primarily to Europe. Then in the 1980s with the opening of China followed by the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, a huge new chunk of the globe was now open for visitors.

While U.S. tourists were the greatest source of tourism revenue during the past sixty years, now it is the new Chinese middle class traveling by the millions, outspending Americans and Germans.

The U.N. announced 2017 as the International year of Sustained Tourist Development but it may be too little to late, so that the more radical question may be, should we limit our travel to our own countries…or stay at home? But this tourist catastrophe is so enormous it cannot be left to volunteerism. Like most economic, environmental and social problems, the solutions demand political action.

The Cruise Industry:

The first challenge for governments and international organizations will be to tackle the colossus on the seas—the cruise ship industry, the fastest growing sector of the leisure tourism industry that generated gross revenue of $40 billion in 2016 while transporting almost 27 million passengers. It also produces billions of gallons of sewage, waste water, oily bilge water and food garbage while burning dirty fuel.

A recent article in Germany’s Sueddeutsche Zeitung: (Aug. 6, 2018) titled: Cruises: a Dirty Business: claims that the cruise ships in Europe burn heavy fuel oil, among the dirtiest of fuels like heating oil which contains a variety of metals including nickel. “When they ply Europe’s rivers, they have no filters on their engines.”

According to Damian Bonmati and fellow reporters in a joint project by Univision and Columbia Journalism School, “A ship traveling for one week with 3,000 passengers and crew can generate: 210,000 gallons of sewage, 1 million gallons of gray water (from showers and sinks), more than 130 gallons of hazardous waste, up to eight tons of solid waste, and 25,000 gallons of water contaminated with oil residues.” Meanwhile more and larger ships are coming on line. Some can carry 5,400 people including more than 2,000 crew members.

The Caribbean cruise lines account for more than a third of the total global cruise business and pollution. Three companies dominate those routes: Royal Caribbean, Carnival and Norwegian. Although headquartered in Florida and courting passengers and income mostly from the U.S., they are registered in foreign countries. Royal Caribbean is registered in Liberia, Carnival in Panama and Norwegian in Bermuda. That means they can avoid U.S. tax, labor, environmental and safety laws

The Univision/Columbia J School investigation revealed that in the past decade these companies spent $31 million lobbying the U.S. government and their “spending categories reflect the areas the industry wants to influence: maritime regulations, taxes and the environment…and during those same years these companies paid less than 1% of their income in taxes.”

Since environmental and government scrutiny began two decades ago these companies have become less transparent in their reporting. The U.S. Coast Guard and others at sea have videotaped cruise ships dumping human waste and plastic bags during the night presumably when passengers are sleeping. Rep. Sam Farr (D-CA), tried repeatedly to get the U.S. Congress to approve a tough environmental legislation bill called the Clean Cruise Ship Act. He tried in 2004, 2005, 2008, 2009 and 2013, but failed to get enough support for the measure. Senator Richard Durbin (D-Ill) introduced a similar bill in the Senate in 2013-14 to a similar response. A U.S. Navy vessel currently has to comply with more environmental regulations than a cruise ship.

There are signs of improvement. Newer ships are built with better waste water and sewage treatment and more efficient fuel usage. However almost half of the cruise ships on the planet today are older models that are pollution and safety trouble-makers. And, even on the new ships, the staff works seven-day weeks for meager wages.

Regions, states, and cities are fighting back. In 2016, the International Maritime Organization banned dumping cruise ship waste in the Baltic Sea. Alaska may have strong marine pollution regulations, but this year a Princess cruise ship was caught dumping oil contaminated water in the port of Ketchikan. This after the Caribbean Princess Cruise line (owned by Carnival) was levied the largest fine ever—$40 million—for dumping oil contaminated water in states along the Eastern U.S., Virgin Islands & Puerto Rico dating back to 2013 and then lying about it. States along the Northeast coast of the U.S. have also instituted more stringent regulations for waste dumping in its harbors. But ships may still dump waste three miles out from the coast.

Many cities now realize that they need to retool their ports so that ships when docked can tap into the local power grid rather than run their highly polluting generators. When a cruise ship idles in Venice for a day it is the equivalent of 12,000 car engines idling. But clearly regulations on the industry require international coordination.

A 2016 Friends of the Earth report card identified which cruise ship companies have improved their air pollution and waste management systems (Carnival received the lowest grade). A recent report from Friends of the Earth calls for action against the continued use of heavy fuel oil on the Carnival line in the Arctic seas. “It’s exhaust contains so much soot that when it is emitted into the Arctic Sea ice it speeds melting.”

Air and water contaminant pollution are not the only issues for cruise ships. Noise pollution below the surface is also environmentally disturbing. Alejandra Vargas, writing for the Univision/Columbia Univ. study, reports on the work of scientists who have been measuring decibel levels that cruise ship engines make in the “vast echo chamber of the ocean.” Studies reveal that whales hear a cruise ship’s engines up to an hour away. “This noise is deafening to the animals and prevents them from locating and communicating with one another until the ship is long gone,” says Christine Gabriele who studied the whales and cruise ship audio pollution from 2000 to 2009.

Beyond the considerable threat to the environment by these floating cities, the economic benefits of the cruise industry to host countries and ports are worth examining. Increasingly the Caribbean cruise ships have become entertainment theme parks fused with a spa resort. Destinations seem less important and consequently the economic benefits for host ports may be diminishing.

Martha Honey of CREST tracks the changes in the Caribbean cruise line business. She reports that cruise lines have cut back on the time spent in port while the companies control most of the onshore excursions. According to CREST, 75% of passengers purchase their excursions on board. And while consumer spending is a lucrative part of the cruise ship industry, passengers mostly buy jewelry and watches at stores that pay commissions to the cruise lines. CREST reveals that commissions from on shore excursions and shops can reach up to 100%. “When tourists stay over in port or on their own travel trips,” says Honey, ”they spend almost twelve times what cruise tourists spend so that “stay over” tourism is far more beneficial to local economies.”

Now the cruise ship companies are setting up their own private islands; so there is little benefit whatsoever to the host country businesses after a leasing deal with the current government administrators.

Ironically, some of the strongest regulations on cruise ships come from Bermuda, the tax haven. They control the numbers of ships docking and don’t allow them into ports on weekends thus reducing competition with local hotels. The government requires ships to stay in port for three or four days out of a seven-day itinerary. Such regulations ensure benefits for the local economy that doesn’t happen with day-trippers.

The lure of a cruise is a cheap ticket that includes a comfortable hotel-like room and all the food you can eat. According to the Sueddeutsche Zeiting article, in Germany alone the number of passengers taking cruises has tripled in the past ten years. Anyone happy with an inner cabin can cruise through Europe for ten days for less than 800 Euros. Last year, 740,000 cruise tourists arrived in Dubrovnik—a city of 40,000. These tourists spend only five or six hours in the historic city center, but don’t spend any money. They go back to the ship to eat and sleep.

Some city and state governments are trying to reign in the onslaught and overcrowding created by cruise ship passengers. The Mayor of Dubrovnik, in an effort to ease the overcrowding of his city, worked with the powerful cruise line association. While he has not been successful in reducing the number of ships that visit the city each year, he has managed to stagger the timing of arrivals and departures.

The mayor of Santorini in Greece has managed to set some limits on the numbers of cruise ship passengers that arrive daily on this tiny island. With a local population of 25,000, on their busiest tourist days they get 10,000 visitors which is threatening infrastructure and resources. Local government wants to limit that to 8,000 visitors daily. But business owners are hooked on the spending of day trippers and have resisted change.

Residents of Charleston, South Carolina, unsuccessfully sued to block the South Carolina port authority from opening up to more and larger cruise ships. Locals fear for the congestion and damage to the historic center along with stress on public services while experiencing little in the way of economic benefits.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the Sueddeutsche Zeitung argues for regulations at the European Union level: “Controlling the fuel types would be a beginning…Also why allow a ship to land that is registered elsewhere without paying any taxes especially for all the environmental stress?”

AirBnB:

Another thorny challenge for governments is controlling the impact of AirBnB on the housing market and ultimately local communities. Cheaper tourist accommodations have contributed to the explosion of tourism in global cities. My husband and I have been part of this on-line phenomenon. We have rented out our house on a vacation rental platform in the past and may again in the future. We have taken advantage of great deals for apartments from Mexico City to Vienna. But the rapid expansion of AirBnB apartments and houses has led to too many tourists in some cities and neighborhoods and skewed local housing markets by removing apartments from long-term rentals. There’s the sense in some cities that over-tourism is transforming the social, cultural and commercial fabric of the community. “This affects people’s feeling of place and local identity,” argues Paul Costello on his German Marshall Fund blog, “as well as their predisposition to accept global and technological developments.”

According to Costello, Lisbon saw its home-sharing listings almost double between 2015 and 2017. Midway, the average rent had increased by 23 percent, pushing many residents out of their city. During the past decade, Costello reports, Barcelona lost half the residents from its Gothic neighborhood “where fifty percent of buildings host some tourists.” Almost 90% of those residents leaving said that “they were leaving because of the increase in rents and because daily life had become impossible.”

In New Orleans, writes Nina Feldman in Next City “the average price per whole house rental per night was $229 — very competitive with hotels, and therefore attractive to tourists. On the other hand, a landlord could only get about $45 a night for the same home if they rented to a long-term tenant,”. In New York, according to Scott Stringer, City Controller, “for every one percent of residences listed on AirBnB, rents in the neighborhood went up by 1.8 percent, causing renters overall to pay an additional $616 million in 2016.”

Hotel associations argue that private residences generally are not held to the same safety standards as hotels, such as requirements for sprinkler systems, handicapped access, emergency exit directions, lighting and fire doors.

The difficulty cities have in regulating AirBnB is to find a middle way between the interests of home-owners trying to earn a bit of extra money along with travelers looking for cheap stays, backed by the considerable lobbying power of AirBnB, on one side, and the affordable housing and neighborhood organizations, backed by the hotel lobby on the other.

So city governments are targeting the real abusers of the system—individuals and companies who list apartments—often more than one per owner—that are never lived in. They are running a hotel business without paying the appropriate taxes. More than half the listings in Lisbon, New Orleans, Boston and Rome are run as full-time businesses.

Elaine Povich writes in The Pew in May, 2018 (May 7, 2018) that “San Francisco this year began limiting the number of nights a year absentee owners can rent their properties through AirBnB or similar platforms. Owners who live in their residence can rent it out without limit.” After the new regulations, short-term rentals dropped by 55 percent.

This year Barcelona told AirBnB to remove 2,577 listings that it found to be operating without a city-approved license, or face a substantial fine. According to Feargus O’Sullivan writing for City Lab (n June, 2018,),the city is also requiring vacation rentals pay the highest property taxes. Barcelona has also limited new hotel permits to avoid more congestion in old parts of the city that have become tourist ghettos. The Balearic islands, Majorca and Ibiza, have also introduced strict regulations limiting AirBnB rentals.

“So far, only Barcelona has successfully coerced AirBnB into giving local authorities access to its data,” reports Paul Costello. New York City’s new law that goes into effect in 2019 strives for similar goals. “If the abuses of this technological platform are not addressed,” argues Costello “the anti-tourist feelings of inundated communities could turn against foreigners in general, globalization and technological development.”

Many of these reforms are piecemeal, inconsistent from one community to another. What can governments do to control the environmental, resource and cultural destruction from tourism? They alone have the power to regulate visas, permits for development, licenses, and subsidies. First, they might learn from several countries that have controlled tourism to their advantage like France, Bhutan, and Costa Rica.

France has been the Number One destination for most world tourists for decades. It began investing in tourism after WWII as a way to re-boot its economy. Through legislation the government regulates hotel and resort development, invests in public transportation, subsidizes agricultural and wine-making regions, invests in the preservation of landscapes including coastlines. And they regulate vacation home rentals.

Costa Rica has designated and protected rain forests and ecological parks. Bhutan controls the number of hotel rooms available and stipulates a specific amount tourists must spend per day.

Other countries are beginning to take control. Denmark has designated “quiet zones” in Copenhagen, limiting bars and restaurants while encouraging tourists to use bicycle transportation. The government has also prohibited foreigners from buying vacation cottages on their seacoasts. Writing in the New York Times, Elizabeth Becker (2015) explains that “the quiet zones are emblematic of the Danish philosophy toward tourists: They should blend in with the Danish way of life, not the other way around.”

Becker also reminds us that UNESCO World Heritage sites around the globe—usually huge tourist draws—are required to have plans to manage tourism. But nearly half do not. She cites Malaysia as a model whereby the government encouraged the participation of residents in the committees to “create a common vision for tourism….residents were also involved in plans to repurpose traditional buildings in ways that would preserve the culture and history of their city while providing financial benefits to the local community.”

What can individuals do?

It is time for the privileged traveling classes to ask themselves some profound questions. Given the invasive and damaging nature of much of travel and tourism, why do we continue to travel? If we must travel, how can we contribute to minimizing the damage?

Foremost, given the seriousness of global warming and climate change, we need to lessen the carbon footprint of our travel. Cheap air tickets along with easy credit for cars are helping to kill the planet. Boats, trains, buses and AC in hotels powered by fossil fuels are contributing massively to our planetary crises. Why not travel closer to home? Can you take public transportation? Can you walk? Bicycle?

Why are you going to the destination you are choosing? Do you really want to be in an over-touristy city where you cannot see the sites for the busloads of bodies and selfie sticks? If you must travel to that congested global city or site, why not travel off season? Better yet, choose a more off-beat destination. Hopefully, somebody will scratch “bucketlist” from our vocabulary. Only 5% of world tourism goes to Africa, and then only two or three countries on that continent. With a little research discover a new destination on the road less traveled.

Bani Amor has written critically about travel that reproduces colonialism, like white folks going off to resorts in the Caribbean or other world locations serviced by low paid workers of color. She argues that travelers should not go to places unless they have a connection to that community.For example, traveling to places connected to your family ancestry. Perhaps that isolated village in Scotland or Senegal.

In her article, “Getting Real About DeColonizing Travel Culture” (May 2017: Medium.) Amor claims that mass tourism “cannot function without global inequality… in communities without sovereignty or self-determination to shape how they want their cultures to be consumed or communicated, their economies to be governed and their environments treated, then tourism and travel culture are only a continuation of imperialist practices…It’s really not a choice communities made. It is made for them.”

Amor represents a new generation of travel writers who once were mostly male and white and not too long ago pronounced travel writing as “dead.” But this formidable new diverse cohort of writers is challenging our concept of travel. “Yes, you can travel and grow, or whatever,” says Amor. “But why do that at the expense of others? Or why can’t you grow at home?”

With privileges should come responsibilities and humility. Perhaps we can contribute time or money to an alternative energy project as a way to counter our carbon footprint? Rain collecting in Mexico, solar panel distribution in Ethiopia, plastic recycling in Sri Lanka, the restoration of degraded environments. Or sign up for classes on local language, history and culture as well as forest management projects. Orphanages? How about visiting one in your own city?

If the natural world beckons, why not explore the surrounding areas of your city until you learn the scientific and indigenous names for places, plants, and animals along with the history of the ecological transformation to this moment.

If your main interest is relaxation and entertainment or shopping, why not enjoy your city, state or country. Spas and theme parks are much closer to home. If you must take a cruise, research all the cruise lines first to discover which has the best waste treatment, air pollution controls, safety history and salaries for workers. Start by asking yourself if that industry represents the values you share.

More affluent tourists aching for a more meaningful journey could start by letting go of the heavily branded “luxury” experience. That hotel chain in Bali similar to the one in Thailand or Honduras. Why not try for something that liberates you from the tourist “bubble” and contributes to local businesses and residents rather than multi-national corporations? Oh, yes, I know—local folks are gainfully employed in those hotels. At the same time those hotels use enormous resources that put strains on the local ecosystem. We need to re-think it all.

Earlier this year my husband and I made a trip to Ethiopia. We had many reasons for wanting to go there. But we are not immune to the lure of foreign cultures and the potential for enlightenment. While we spent money on the domestic airline, local hotels, restaurants, drivers and guides, and bought crafts, we avoided one of the big tourist pulls in Ethiopia: The expensive gawking tour of the exotic tribes of the south. The Omo region. A safari to ogle colorfully decorated people rather than animals. It’s not clear that the tourists who make that journey are contributing anything but germs to these isolated bush tribes.

The attraction to such exotic “others” is a legacy of the 19th century European upper class desire to see the peoples of the Near and Far East, North Africa and the South Pacific, all envisioned by artists and writers following the imperialist project. Their artistic output sparked the imaginations of the traveling classes back home. Edward Said’s 1978 book, Orientalism, addresses the “romanticizing” of non-European cultures and the superiority that suffuses European scholarship, creative work and ultimately political attitudes toward these parts of the world. Sadly, this ideology continues to inform tourism in our time.

But If we are still driven by the desire to “know” or “witness” the “other,” and we are from North America, it might be more significant—and transforming—to visit a First Nation reservation in Canada or the U.S. to learn more about their history, cultures, thinking and challenges confronting centuries of annihilation.

Some critics recommend “slow travel.” Perhaps a walking tour or pilgrimage that forces us to think deeply about landscape and nature as well as local people and traditions. But please don’t pick the Santiago Compostelo pilgrimage in Spain. It’s already mobbed with tourist walkers, is on or close to busy paved roads, never out of earshot of autos, motorbikes and cell phones. There are many other pilgrimages and trails including gorgeous deep nature ones in the U.S. and Canada. You might enjoy reading Torre DeRoche’s The Worriers Guide to the End of the World for the wonders of two women making a pilgrimage on foot through Northern Italy and Ghandi’s route through India. “Nothing is more inviting,” writes DeRoche, “than a destination reached by slow progress and hard work; its position on the planet and distance from everything else is so intimate to you because you’ve slowly traced the skin of the earth to reach it.”

DeRoche is one of those new travel writers worth exploring. “The only thing that seemed to matter to anyone,” she concludes, “was that we were pilgrims who’d embarked on a long journey for the same reason that all seekers seek: so we might come upon some proof that we’re something more than ridiculous meatbags filled with warm guts flying through black space on a giant blue ball.”

European writers, painters, and philosophers, during the Romantic era of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, extolled the virtues of solitary walking or hiking in nature as a means to contemplate the meaning of life, the environment and one self. “Wanderlust is, historically, a German idea,” writes Cody Delistraty in the Paris Review, “Wandern, meaning to hike or to roam, and lust, of course, meaning to desire, began not as a leisure activity but as a serious existential exercise of going out into nature in order to go into oneself.” Writers and painters during the Romantic era saw “travel as a way of opening up the soul,” says Delistraty…a pilgrimage within the self.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote a series of essays, Reveries of a Solitary Walker in the late 18th C that reflected on the meditative spirit of nature at a time in his life when many of his friends had deserted him. These essays influenced one of his contemporaries, feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, who with much pain and courage, was a solitary walker through most of her life—heading alone from London to Paris during the French Revolution to write about it and then produced a reflective travel book about her lone journey through Scandinavia as a single mother with an infant in tow.

Rebecca Solnit pushes us further challenging us to get lost. In her Field Guide to Getting Lost, she claims, “Never to get lost is not to live. “ When we get lost, she argues, the world has become larger than your knowledge of it. It means letting go…and the potential for discovery. The explorer is the person who is lost. “When lost – we own the unknown.”

Solnit quotes Thoreau for whom navigating life and wilderness and meaning are the same art: “Not till we are lost, in other words, not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.” It’s Biblical, says Solnit, “Lose the world, gain your soul.”

Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities imagines conversations between the great Mongol Emperor, Kublai Khan, and the famous traveler and travel writer, Marco Polo. “The more one was lost in unfamiliar quarters of distant cities, the more one understood the other cities he had crossed to arrive there, “ which might translate to the trope that the farther we travel from the familiar and home the more we appreciate or understand where we are from.

So few travelers I know return with a “take” on another culture. Insights. Keys. Partly it’s a problem of language. Few North Americans are willing to grapple with another language. And since tourist journeys are short, the takeaway is a description of a hotel, some food, a few bits of landscape, a story or two. Here is where inspired literary travel writers have provoked us, highlighting the question as not “What have I seen?” but rather “What is it that I have seen?” How can we abstract our observations and insights? In an era of mass migrations, environmental crises and re-aligning geo politics what are the potent symbols that offer a key to understanding another place, society, eco system, culture?

If the best of our lust for travel is about enlightenment, then reading fresh voices on our world could constitute a substitute for polluting and invasive physical travel. Take for example, Between the Sunset and the Sea: A View of 16 British Mountains by Simon Ingram, a non-macho walk through significant mountains, while discoursing how they came to dominate our imagination. Chapters are filled with poetry, science, terror, death and art. Or Emily Raboteau’s Searching for Zion traces her journey from Israel to Jamaica and Ethiopia where she explores the roots of Black Jews, Rastafarians and historical ties connecting them. Or check out panoramica.com an online journal of new travel writing from authors all over the globe.

Ok. Ok. You and me. Driven by the desire for knowledge, thirst for adventure, experience and encounters with the rest of the world, we will probably not stop traveling. But tourism’s threat to the globe demands we confront our denial about the crisis we are helping to create. We must change our course.

Years ago, when I read Bruce Chatwin’s SongLines, I did not need to rush to Australia. I had learned so much that cracked my skull that I could dream about it in the comfort of my own bed.

* * *